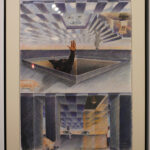

An art exhibition of works by college and high school students spanning the career of the art educator who taught them is on display at Raw Space in Vero Beach through Feb. 26. “The Grid Comes Full Circle II” is a collection of 64 works by young and continuing adult artists in drawing, printmaking and collage.

The audience for this show is anyone, young or old, who loves art with something to say. The art in this show is frequently topical, often politically so, and is always beautifully crafted.

The educator behind this bounty is Terry K. Hunter, Ph.D., who began his teaching career in Orangeburg, S.C., in 1977, when he was hired as a professor of drawing and printmaking at South Carolina State University. He has made Orangeburg home ever since, where he shares his life with his wife, South Carolina State Rep. Gilda Cobb Hunter.

All the works in this show are from the collection of FACETS (Fine Arts Cultural Enrichment Teaching Studios), a nonprofit foundation of which Hunter is the executive director. In addition to organizing and traveling exhibitions such as the current Raw Space show, FACETS’ stated mission is to “provide instruction and professional development opportunities in the visual arts.” It does so by developing workshops in the visual and performing arts aimed at residents of Orangeburg County and surrounding areas.

You might be asking yourself, what does Hunter have to do with art in Indian River County?

Hunter attended high school here in the days before Indian River High School was desegregated, in 1969. As a Black student, he first attended Gifford High School. There, his art teacher was Willie C. Reagan, who is today best known as one of the original members of Florida’s Highwaymen landscape painters.

In February of last year (how long ago it now seems!) teacher and student shared Raw Space in a two-person show that included Reagan’s paintings and Hunter’s drawings and prints. That exhibition was titled “The Grid Comes Full Circle I.” Although the two artists’ work share little in common in subject matter or style, the show was a testament to the influence that Reagan’s teaching had on Hunter.

After Hunter graduated from high school in 1971, he attended college at Florida A&M University, where he received his Bachelor of Arts in Art Education. He went on to earn his Master of Fine Arts at Ohio State University, , majoring in drawing and printmaking, and a doctorate in Art Education from Florida State University.

The current exhibition, “The Grid Comes Full Circle II,” gives pride of place to Hunter’s own students. The show is divided into three sections that speak to the three eras of his teaching career.

The first section is devoted to work by students that Hunter taught during his 1977 to 2000 tenure at South Carolina State University, where he taught freshman foundation classes as well as upper-level drawing and printmaking classes. During the same period, Hunter taught art to students in sixth, seventh and eighth grades at Felton Laboratory Charter School on the campus of South Carolina State, as well as at the South Carolina Governor’s School for the Arts and Humanities in Greenville, a residential high school that also offers summer programs.

One of the earliest works displayed under this section is a 1977 linoleum cut print by Felton student Charles Davis. Titled “Room Service,” the lively print depicts the lower half of a kangaroo whose long, skinny feet with fat, upturned toes are counterbalanced by a scraggly tail that is more prehensile than prop-like. The “room” of the title is the kangaroo’s pouch, of course, from which a baby kangaroo peeks.

As is the custom with professional printmakers, the middle-school student signed and titled his work in the print’s lower margin. He also wrote the word “Proof” there. A print proof is more than a trial print but not yet part of an edition. In printmaking terminology, it is the first print the artist makes that has all the features the artist wishes to see in it. The successful “pulling” of a proof print means that the edition is ready to be printed.

From the word “proof” on young Davis’s print, we learn two things: that the student intended to make an edition of numbered prints of the image, and that Hunter made sure that even his youngest students were aware of printmaking terminology and practices from the get-go.

College student Robert Generette III received his BA in art education in 1989. His woodblock print in the exhibition is composed of tapestry-like slashes of black and gray ink that coalesce into the close-up portrait of a serious young man. “Youthful Expressions II” is also a masterful expression by a young artist who, as his current LinkedIn profile has it, has “been imitating life and expressing myself through lines since the age of three.” Today Generette is a freelance illustrator whose specialty is pop culture and sports portraiture.

The text panel that introduces the second section of the exhibition is titled “The Claflin Years (2000-2006).” It refers to the six years Hunter taught drawing and printmaking in the art department of Claflin University, a private, historically Black institution founded in 1869. From the start of his engagement at the school, Hunter also team-taught art foundation classes with the department’s chairman. In 2001 Hunter was appointed the first director of Claflin’s newly established Arthur Rose Museum. Rose (1921-1995) was a Claflin art educator and artist who is still hailed as the Dean of Black Arts in South Carolina.

The students at Claflin did not disappoint Hunter’s exacting standards. In this section Tiffany Bodison’s 2000 screen print “Winds of Fertility” shows the profiles of two women of color (deep turquoise on the left, amber brown on the right) facing each other. Against a golden yellow background, the faces frame a central image of an Ashanti Akua’ba doll, a small, carved wood sculpture representing a beautiful child. It was once carried by Ashanti women who wished to become the mothers of healthy, attractive children. The doll seen in this print has two twisting strands in place of a solid body; perhaps this refers to the modern conception of DNA, a scientific notion that unites generations of people as surely as their cultural traditions.

At Claflin as well as at South Carolina State, Hunter developed and ran URGES (Upper Room Graphic Editions Studio), an independent study program in printmaking and drawing. One of the students in the program was Daniel Moss, whose “Matters of the Heart” linoleum cut of 2002 shows a bandaged heart suspended over a crowd of people, some of whom appear to have wings. The numbers 9-1-1 appear in sequential boxes at the top of the image. Perhaps the print is a reference to our nation’s mourning for the events of September 11, 2001; the imagery could also refer to the personal grief of families whose loved ones died on that day.

Whatever the reference, the work, in simple black ink on white paper, is a tribute to the power of the linocut to address contemporary issues.

The final section of the exhibition is devoted to those students who have been part of the continuing education studio classes that Hunter offers via his FACETS foundation.

\The artworks from the most current part of Hunter’s career, 2006 to today, include those by students who were taught by Hunter as undergraduates, while others are by art teachers, both newbies and veterans, who enroll in FACETS’ intensive summer sessions to recharge their creative batteries.

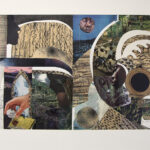

Five of the most intriguing works in this section, however, are works in collage by an artist who Hunter asserts had no previous art experience before attending FACETS classes. Those works are by Angela Corbett, who loaned to this exhibition. All are eye-catching, intricate arrays of colorful papers, hand decorated by Bassett and arranged into compositions of spirals and cubist fields, that come together into the shapes of flags and other symbols. One of these, “Shattered Glory,” depicts the Confederate Stars and Bars disappearing into the swirling sky above it and a patchwork of fields below. On the latter a swastika shape is clearly visible.

The Confederate flag was finally removed from its pole at South Carolina’s state capitol in 2015. Corbett’s 2020 work seems to say, “Yes, the flag is disappearing, but what it stood for still stains the land.”

Photos by Kaila Jones