Good things come in small packages, and the current Vero Beach Museum of Art exhibition of etchings by Australian-born American artist Martin Lewis is a very good thing.

The concept for the exhibition came about during the tenures of VBMA director Lucinda Gedeon and curator Jay Williams. It was brought to fruition under the direction of the VBMA’s new director, Brady Roberts, in concert with the museum’s new curator, Danielle M. Johnson. The passing of the baton from the emeritus to the current museum professionals could not have been done in a more graceful manner.

Installed in the Titelman Gallery, “Shadow and Light: The Etchings of Martin Lewis” is so virtuous that the VBMA has published a catalog of the same title for the show. That does not happen every day; the last catalog the VBMA put out was for its George Rickey exhibition, back in 2007.

The prints in the current exhibition are from the collection of Vero Beach resident Stephen Holcomb, who also sponsored the catalog.

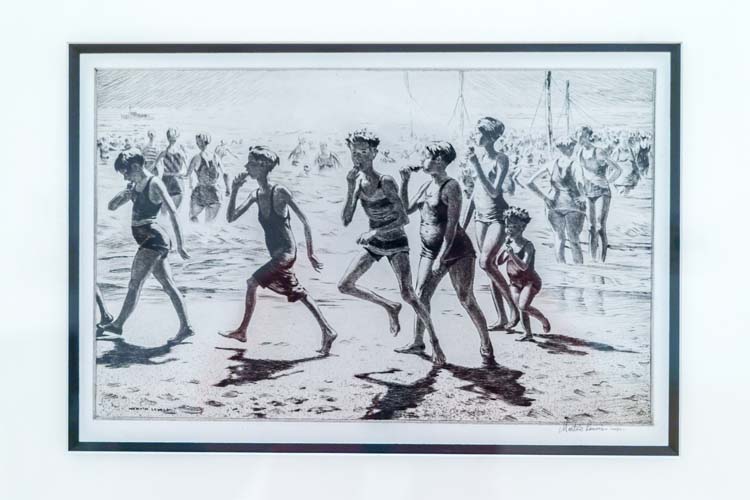

Standing at the entrance of the gallery you might first be struck by the inviting look of the 54 prints on display: numerous etchings in the drypoint technique, often combined with other techniques, including sand ground, acid etch and aquatint. The show also includes two mezzotints and three lithographs.

Printed in rich black ink on paper whose whiteness varies in tone from cool to warm, the etchings are mounted in newer frames of dark wood discreetly touched with gold leaf accents. Many of them are double-hung, one above the other, for an effect that suggests the comfortable environment of a private collector’s home.

The subjects of the prints include dramatic visions of New York City and environs in the early decades of the 20th century. The earliest print on display, “From the River Front” of 1916, features the silhouette of a downtown skyscraper that stands head and shoulders above its high-rise companions. The immediate foreground is occupied by a vastly more humble district, whose denizens bustle about in the feeble light of a crepuscular sky. New York City’s juxtaposition of the old and the new, the meek and the mighty is just the thing to elicit wonder in the mind of a newcomer to the city. The shadowy tones of Lewis’ print on that subject foretell his career as a master of night scenes.

And what scenes. Lewis had an affinity for the City that Never Sleeps – not only for the ship-churned Hudson with Gotham beyond it that he shows us in “Passing Storm” of 1919, but also for the people of New York, who endlessly tread the electrically lit streets of the city.

Over a career that spanned five decades, Lewis’ fascination with portraying the effects of artificial light in his scenes of city and town never dimmed. Like his contemporary and friend, Edward Hopper, Martin Lewis was a poet who used light and locale – the city and its suburbs – to describe both the nostalgia and essential loneliness of American life during a time of rapid change.

Unlike Hopper, who was born in 1882 not far from the city in Upper Nyack, N.Y., Lewis was not American by birth. Born in 1880 in the town of Castlemaine, Victoria, Australia (a little over 80 miles northwest of Melbourne), Lewis arrived in New York as a young adult. In his childhood, he took drawing lessons before leaving home at 15 to travel in Australia and New Zealand while working as a manual laborer. He settled briefly in Sydney, where he studied at Sydney Art School under the English-born painter Julian Ashton. Lewis was 18 or 19 when he left Australia for the United States, working his way to San Francisco as a merchant seaman. By age 25 he had found his way to New York City. Already an accomplished draughtsman and etcher, Lewis created his first etching in New York in 1915 while supporting himself as an illustrator. It was during his early years in New York that Lewis showed Edward Hopper the basics of etching.

The early influence of Japanese printmaking on Lewis’ art at this time can be seen in two almost identical prints, hung one above the other, in the current exhibition. “Moonlit Farm Scene” depicts a sleepy little house above which a full moon peeps between the drooping branches of a weeping tree. Both prints were pulled from the same copper printing plate; each is a variation on the same image. The print hung topmost shows a sharp, clear moon in a starless sky; the lower print shows a soft, hazy moon with two bright stars shining some distance above it. At least three prints of each variant are known to exist.

Although it is not specified which print version came first, the assumption can be made that the variation with the two stars was the latter state. Lewis used two different techniques to create the image: acid etching and drypoint. In that latter, a needle tool is manually drawn across the plate to incise lines into it. The soft moon and stars in the lower print were achieved by selectively flattening and/or scraping away the lines so they will hold less (or no) ink, thereby allowing the white of the paper to show through in those places when the plate is printed.

Drypoint is a demanding technique that requires a steady hand and a sense for the right amount of pressure with which to pull the needle to achieve thicker or thinner lines on the plate. As the needle carves into the copper, it throws up a ragged burr of metal on either side of the needle’s path. When the artist inks the plate, the incised line and the burr will both be filled. This results in a soft, dense black line when the ink is transferred from plate to paper in the printing press. The variety of tone as well as the richness of the black in a Lewis drypoint print is a thing of beauty to lovers of fine prints. That beauty, however, is achieved at the expense of the incised drawing on the plate. Copper is soft, and the delicate burring, as well as the lines incised into the plate, are soon worn down under the pressure of repeated printing. At best, a couple dozen impressions can be taken before the image begins to visibly degrade. The electroplating process allowed Lewis to print some of his plates in larger editions. Electroplating protects the surface of an etched copper plate by placing microscopically fine layer of steel over its surface.

Lewis left New York for Japan in 1920, initially with the intention of living there permanently. After two years spent studying Japanese art as well as creating paintings and drawings of his surroundings, Lewis returned to New York. The prints he made in New York after 1925 show how much he learned about composition, texture and mood from his experiences in Japan. There is one print with a Japanese subject in the current exhibition. Dated 1927, the drypoint shows a street booth on New Year’s Eve in Toyko, where passers-by are in its electrical brilliance.