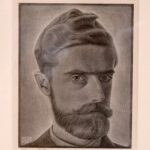

The current Vero Beach Museum of Art exhibition, M.C. Escher: Infinite Variations, is a fascinating mix of works by Maurits Cornelis Escher (1898-1972), an acclaimed graphic artist and printmaker, whose mind-bending optical illusions, and what he called “mental imagery” artworks, challenge logic and reality.

The single-source, traveling exhibition, which features 160 woodcuts, lithographs, drawings and mezzotints, is on loan from PAN Art Connections, and on view through Dec. 30.

“I like to imagine what people thought back then. Because there was nothing like it at the time,” says Dr. Salvatore Iaquinta, an otolaryngologist with a passion for Escher, who serves on the board of the M.C. Escher Foundation. “We’re used to seeing optical illusions and all that now.”

The exhibition spans Escher’s career, from his early Italian landscape sketches and portraits to his revolutionary images of impossible construction and infinity works. Among his most iconic artworks are tessellations, a type of geometric tiling that repeats forever in all directions; metamorphosis pieces, which effortlessly transform, for instance, birds and fish; and his fascinating reflections, of mirrors, spheres and eyeballs.

Iaquinta explains that although mathematically oriented patterns are rampant in many of Escher’s works, he decided to become an artist rather than an architect, as his father had wished, because he wasn’t very good at math. Ironically, despite that lack of architectural schooling, his works are also rife with cityscapes, draftsmanship and structural designs.

Greatly influenced by his travels, Escher derived as much from the geometric tiling patterns of the Alhambra in Spain, as from the landscapes and vistas of Italy and the Mediterranean.

“He spent a lot of time on the Amalfi Coast and used the background of those early drawings when he started creating his more fantastical works,” said Iaquinta.

“Escher started doing lithographs in the 1920s; he had done just wood cuts before that. It wasn’t until the 1940s that he started doing mezzotints [copper plate]. He only did eight of them, but they’re all here.”

Many of the works on display are quite rare, including “Rome and the Griffin of Borghese,” a 1927 woodcut.

“A lot of the ones before World War II are really hard to find because they’ve been destroyed.

But also, he was selling these on the street; it’s not like he had a gallery,” Iaquinta explains.

He adds that even works from the 1950s have pinholes or tape, as they were often treated as posters.

Iaquinta says “Saint Francis (Preaching to the Birds),” 1922, featuring the saint ‘preaching’ to a rapt group of birds, was Escher’s transition piece. “This is the first piece Escher did when he decided, ‘I’m going to be an artist and I’m going to sell my work.’”

In the early 1930s, Iaquinta says, perspectives get a little more fantastical, as in “The Bridge,” a 1930 lithograph depicting an area of Southern Italy.

“Like in real life, this bridge isn’t here; he added it in,” says Iaquinta. “Which doesn’t sound like a big deal, but for him it’s actually a transition. Because as you look at a lot of these lithographs and woodcuts from that time period, they’re really photographic type renderings. And here he’s just starting to play with things; shift the perspective a little bit to make things a little more fantastical.”

Because Escher kept a diary and saved everything throughout his life, scholars can see how his artwork evolved. Iaquinta explains that “Cycle,” 1938, where a figure rushes down the stairs and loses his identity to become part of the pattern, is one of the last tessellations he made with a character upside down.

“At some point, somewhere around 1930 to 1939, he came up with all these rules, like he doesn’t want an animal upside down.”

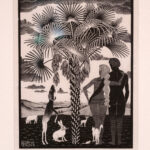

“Day and Night,” 1938, is one of Escher’s largest and most iconic tessellations. In it, gray rectangular fields develop upwards into silhouettes of white and black birds flying in opposing formations.

“The overlapping of the night and day skies was a theme Escher returned to over many decades. And over the years, Escher collectors kept returning for this work. Escher journaled that it was his most popular woodcut,” Iaquinta explains.

“He wrote in his journal that this is the print he sold the most. He printed this about 645 times during his life. That kind of gives a sense of how few Eschers are out there.”

Iaquinta says Escher called his surreal “Dream” series, created in the early 1930s, “finger exercises,” a way to practice such techniques as using single lines to create images. It also introduces us to Escher’s fascination with insects and reptiles.

“Dream (Mantis Religiosa),” 1935, features a praying mantis overshadowing a bishop’s sarcophagus, and Iaquinta explains, “It was based on three different drawings from different years. In 1930 he was sitting on a hillside and a praying mantis crawled on his leg, and then in 1935 he put it all together.”

Iaquinta says another thing Escher struggled with was how to contain a tessellation.

“Because if you think about it, this pattern can go on forever. But he didn’t like the idea of cutting off animals mid-section. So he was always trying to find ways to contain them,” he says.

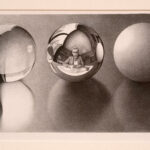

Escher’s fascination with reflections is demonstrated in “Eye,” 1946.

“That’s his own eye. He put a skull reflected in there,” says Iaquinta. “He said the only thing he could think of that would be a universe of reflection is the grim reaper.”

“Drawing Hands,” 1948, in which two hands are implausibly sketching the other, is another famous piece, although Iaquinta says most people don’t know who the artist is.

“It’s a mirrored image of his hands because he was left-handed. When you do a lithograph, everything prints in reverse.”

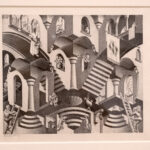

His well-known gravity defying “Relativity,” 1953 will be recognizable to the younger set from its appearance in the 2014 movie, “Night at the Museum – Secret of the Tomb.”

“The art gallery becomes the entire world that the figure is in; it spirals in on itself forever.

As the figure comes into the gallery, it keeps turning and turning and turning.”

Escher printed most of his works by hand, rather than using a press, and could print woodcut pieces to order. He preferred working in black and white, using one block – generally pear or maple – for each shade of gray/black.

On the other hand, he owned just a dozen lithograph stones, wiping them clean to create something new. As a result, he couldn’t later print additional copies.

“Sometimes, when he was coming up with an idea, he would lock himself in his office for days at a time, and then he’d come out all excited,” says Iaquinta, adding that once he started on the technical aspects, the children were allowed to make noise again.

In the 1960s, Iaquinta says, a lot of Escher’s artwork was used illegally, particularly for album covers and blacklight posters.

“He never gave permission; he actually turned down Mick Jagger twice for requests to do album covers.”

For more information, visit VBMuseum.org.

Photos by Joshua Kodis