If paintings could speak, what would they say? Or, rather, what would they sound like? A Helen Frankenthaler might emit a low hum. A Joan Mitchell would have a syncopated snare drumbeat with a rimshot here and there. Robert Motherwell’s Elegy to the Spanish Republic series has the echoing sound of a steel door banging shut. Some of Jules Olitski’s paintings ring like gongs, while others clash like cymbals.

Vero Beach artist Susan Hale says she loves the work of all of those contemporary masters.

Her own paintings, in watercolor, acrylic, oi, and mixed media, possess a peaceful silence. The kind of silence that, as when you are alone on a forest path, you would hesitate to break by speaking aloud.

Take, for example, her mixed-media work, “Palimpsest.”

The surface of the 12-by-12-inch panel is black, furrowed with grooves and lanes that reveal an underlying paint layer or two. The lines abut and sometimes cross over lake-blue shapes, while small red shapes overlay what, on a topographical map, might indicate towns or other human-made structures.

That painting makes the sound of a monastic scriptorium in which only the gentle scratch of quill pens breaks the silence.

Back in the days of parchment (animal skin) documents, a palimpsest was a manuscript that had been scraped clean of writing and reused to create a new document. This was sometimes done because the process of preparing calf, sheep or goat skins and binding a new document was time-consuming and expensive. Scribes from ancient times onward would not only scrape out and rewrite mistakes in their hand-lettered documents, but also scour pages of entire books to create completely new manuscripts.

The term palimpsest also refers to what Hale has recently become interested in creating: artworks in which previous layers of work have been selectively covered and/or removed to arrive at the artwork’s final form, complete with glimpses of its sub-strata.

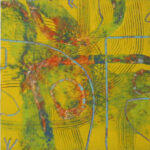

Other artworks done in the palimpsest manner dot the walls of Hale’s workspace. “Bird’s Eye View” has a similar map-like appearance. In it, fertile green and hothouse red swathes disperse over a yellow sea inlaid with cobalt channels. “Arroyo, New Mexico” is deep orange-red. You can almost hear a Martian wind blowing across its otherworldly surface.

“I did a whole lot of these 12-inch-square paintings,” says Hale. She explains that while she painted most of those works in acrylic, she painted a few of them in oil mixed with a cold liquid wax medium.

“I mix 20 percent wax to 80 percent oil paint. To begin a painting, I just start making marks that eventually get all covered up. I begin to scrape away areas of pigment, and cover areas with additional pigment, scrape away, and then cover again. I make comb marks with a notched adhesive spreader. I use all kinds of tools, not just brushes. I have tools that I repurpose for painting, tools that I make, and tools, for example sticks, that I find.”

Hale doesn’t know how many layers of paint she typically applies to complete a painting. But she has taken photographs of her process.

“I have whole series of the progress of some of my paintings, from the beginning to the final layer,” she says.

Hale’s latest explorations in paint are unlike the spare watercolor style she is perhaps best known for in Vero. However, her restrained touch continues in other recent works in acrylic on board as well as canvas substrates.

In one untitled work on canvas with a limited palette of red, white and Payne’s gray (a bluish-black pigment), Hale tempered her hard-edged geometric composition by describing some of her forms in translucent zinc white paint that incompletely hides the colors and shapes beneath it. The dribbly white and gray washes she allowed to run down the face of her canvas imply that the sharp boundaries of her triangles and quadrilaterals are not as impermeable as they might seem.

Says Hale, “I like the drips. You see, that’s a totally different thing for me. I like to do different things.”

Another untitled abstract resembles boulders set in a Zen Garden. Hale cut stencils that she used to create her black, monolithic forms. That painting makes the noise of a single hand clapping.

One of Hale’s recent works, an indigo and pink oil painting, whispers of memories. “I think of it as a mountain in the mist. Softness,” she says.

That one was inspired by the rocky landscape of New Hampshire. Hale has vacationed there on Squam Lake since her childhood.

“My mother’s family, starting with her great-grandfather, has been going there for a long time. It is a magical place.”

So is Vero Beach, where she was born and raised.

Hale is one of four children. Her mother, Margaret “Polly” Dexter Hale, was from the Boston area. Her father, Stephen C. Hale Jr., was born in Rochester, New York. He attended high school and college in Atlanta, after which he entered the U.S. Navy as a commissioned officer.

Her father finished his naval career in 1946, after he was transferred to Vero Beach’s Naval Air Station with Polly and their first two children in tow.

“My father used to come down to Florida from Georgia on vacation. He loved the climate, and he loved the idea of selling citrus. When he came down here after World War II, he had in mind to start a little mail-order fruit business.”

Hale Groves eventually became a giant among seasonal fruit shippers.

Susan Hale left Vero Beach to attend Colby Junior College (now Colby-Sawyer College) in New Hampshire. There she majored in Spanish, in which she is still fluent. Through the auspices of Washington, D.C.’s Georgetown College study abroad program, Hale spent her junior year as a visiting student in Madrid, Spain.

She and two other American women lived in a large house over which a trio of widows presided. The Franco dictatorship was then on its last legs, but Hale was young and thrilled to be studying the works of Spanish philosophers in her adopted language, frequenting the Prado, and traveling in Europe during school breaks. She finished her degree at American University in Washington, D.C.

“I minored in the history of art in college, and I took a painting course at American University. I didn’t get a master’s degree. I wanted to get out into the world and start working,” she says.

One of Hale’s first jobs was translating English school texts into Spanish. She then worked for the Institute of International Education, where she planned itineraries for international scholars visiting the U.S. Hale worked briefly in public television before joining the marketing department of the Washington Post “during the time of Watergate.”

She returned to Vero Beach in 1993 to help with the family business. Following her father’s death in 2005 the business was sold, and Hale adapted to life as a full-time artist. Her job now, she says, is “looking for beauty.”

And that is what makes her work in painting a resounding success.

Photos by Kaila Jones