If you ask Sophie Bentham-Wood, Vero Beach Museum of Art director of marketing, what has been bringing people into the VBMA to see the current “Vero Collects” exhibition, she starts off by saying that the drastic reduction of new COVID cases here has given everyone a little more breathing room.

“This is the first time we’ve really opened up since the pandemic,” she says. “We are just beginning to come back with the group tour offerings.” She notes that visitors have once again been taking advantage of their very popular 2 p.m. docent tours.

Bentham-Woods opines on the appeal of this particular exhibition, which has been drawn from local private collections.

“A lot of people have an interest in what other people have in their homes, and that has increased visitation. In addition, the catalog that Anke put together has been incredibly popular in our gift shop. We’ve got a small print run that we might continue on with, because the catalogs have been very, very popular,” she says.

The catalog features full-page color reproductions of every object in the exhibition.

Notes by senior curator Anke Van Wagenberg briefly explain the art historical significance of the artist behind each piece.

Van Wagenberg admits that putting the show plus the catalog together was a lot of work, but it was fun work.

“I made visits to collectors all over Vero Beach, and basically everybody showed me their entire collection. I saw every nook and cranny of a lot of homes,” she says. “People have passions about their collections. I went to 51 homes, I believe, and everyone agreed to loan to the show.”

You might be wondering, do collectors in Vero purchase helter-skelter, this and that, without any thought of giving a shape to their holdings, or do they take an organized approach to building their collections?

“Most people buy what they like, and especially what they want to live with. There are several focused collections in Vero,” says Van Wagenberg, who mentions the very specific collection of Stephen Holcomb and Hollis Harman.

That treasure trove holds loads of prints by American printmaker Martin Lewis. A number of that collection’s artworks was last seen at the VBMA in its 2018 exhibition, “Shadow and Light: The Etchings of Martin Lewis.”

Lewis’ best-known prints feature New York City’s bustling streets at a time when bobbed hair, cloche hats, low waistlines and high skirts were de rigueur for modish women of all classes. In the current exhibition, Lewis’s drypoint print “Glow of the City” focuses on a slender woman who has stepped out onto her apartment’s fire escape landing for a breath of cool evening air.

Hanging above her head, clotheslines adorned with a motley assortment of laundry stretch across a dark void to the opposite row of tenements. Rising behind those buildings is the 56-story art deco Chanin office building. That structure was completed in 1929, the same year Lewis’ print was executed. Back then the light array at the top of the Chanin Building emitted the equivalent of 30 million candlepower. On a clear night, the light could be seen more than 40 miles away (thank you, Wikipedia).

Lewis’ aptly named “Glow of the City” celebrates the power of modern Manhattan. The poignancy of the scene – not to mention its romance – is due to Lewis’ decision to place the new skyscraper in the background of his human-scaled theme.

Says Van Wagenberg, “The Martin Lewis collection is everywhere in the collectors’ house.

They collect very specifically. They like Martin Lewis prints.”

Van Wagenberg says that a lot of the collectors she visited are not only enthusiastic about their collections, but also “very knowledgeable” about the art they collect.

“Other collectors collect only African-American art,” she says, and names two such couples:

Nancy and Russell Brewer, and Eddie and Sylvia Brown.

In the current show, the Brown Collection is represented by American Beauford Delaney’s untitled painting from his Greene Street Series of 1940. Greene Street runs through the now-trendy SoHo neighborhood of New York City, but when Delaney lived on the street in the 1930s and 1940s (his home/studio there has long since been demolished), it was a neighborhood of pushcarts and physical labor, where Black men wheeled and hefted great sacks of merchandise from one place to another.

In the year Delaney created this picture, city planners had given up on the neighborhood. They deemed it obsolete, fit only to raze in preparation for new construction. That did not happen. More artists began moving in for the cheap rents, and gentrification followed.

Instead of the junk store prominently displayed in Delaney’s painting, the area now boastsluxury apartments and boutique shops.

From the Brewer Collection came a suite of six Romare Bearden prints, a painting by David Driskell, and a Jacob Lawrence drawing of a Nigerian marketplace executed in colored crayon.

Of the latter, Van Wagenberg says, “‘Memories of Nigeria’ is an amazing piece from when Lawrence went to Nigeria in 1964 on a travel grant. It is very rare to see an artist make such a beautiful thing in a children’s medium.”

A medium that is as near as the smartphone in your hand, and nowadays as elemental as a child’s crayons, is photography. That medium is represented in this show by prints executed with 20th century technology.

The Elizabeth Stewart Collection is composed entirely of works in photography. From that collection, three gelatin silver prints by three masters of the medium hang in close proximity to one another in the Holmes Gallery. They are the work of Americans Ansel Adams and André Kertész (born in Hungary), and the Brazilian Sebastião Salgado.

Kertész is represented by his “Washington Square, New York (No.17)” of 1954. The image is one of Kertész’s most recognizable for the poetic elegance of its snow-covered composition.

Salgado is represented by “Fortress of Solitude,” of 2005. The globetrotting photographer uses only black and white printing methods to present photographs of the natural environment, as well as the people who live and work in the remote places he visits. The subject of his print is an Arctic iceberg, atop of whose jagged back rises a perfectly formed rectangle of ice, the “fortress” of the title.

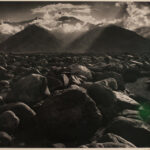

“Mount Williamson, The Sierra Nevada, from Manzanar, California” of 1944 (printed in 1977) by Ansel Adams is intriguing not only for its breathtaking, boulder-strewn landscape, with the distant Sierra Nevada mountains rising into the clouds. The scene is also remarkable for its proximity to the desert “relocation center” i.e., internment camp, where the U.S. government stowed 110,000 men, women and children of Japanese descent during the Second World War.

Adams, that great documentarian of the American West, took pictures in 1943 of life inside the camp. It was his only venture into photojournalism. Adams took pictures of the hastily constructed barracks in which the people lived, and the lives they managed to construct for themselves within the camp’s guarded confines.

The portraits Adams made of the internees’ faces emphasized not only their humanity, but also their essential Americanness, right down to the U.S. Army and Navy uniforms a number of the young men and women wore when they visited “home” on leave.

Van Wagenberg says of the piece that it is “exceptional.”

“This is what the people who were living in Manzanar actually saw. This an unusual landscape in that sense.”

The variety of artworks on display in Vero Collects is exceptional. How did Van Wagenberg choose what she wanted in the show?

“Well,” she says, “I wanted to follow the mission of the museum, so I selected modern to contemporary, European, and American artwork. I didn’t want to have a whole section of something else, right? Like Chinese pottery or African tribal art. That would have meant that I would have had to create a whole room to display those objects in relation to comparable objects, so I just wanted to follow the mission of the museum.”

Photos by Kaila Jones