The Vero Beach Yacht Club recently hosted a reception to honor World War II veterans and to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the end of the war. In Europe, Germany signed an unconditional surrender on May 7, 1945 in France, and in the Pacific, Gen. Douglas MacArthur accepted Japan’s formal surrender on Sept. 2, 1945 aboard the U.S. battleship Missouri, anchored off Tokyo Bay.

Three veterans at the reception, each 95 years old, served in the U.S. Navy and were in the Pacific when the war ended.

Leavenworth (Lem) P. Sperry Jr. served from February 1944 until his discharge as a Lt. Jr. Grade in May 1946. Sperry would go on to serve as president and CEO of Waterbury Companies until his retirement.

The bulk of Sperry’s service was aboard the USS Pochard, a 220-foot minesweeper made and newly launched from Savannah. The ship traveled through the Panama Canal, up the coast, over to Hawaii and west to Eniwetok, “a little dot on the Pacific Ocean that was hard to pick up on radar,” to Guam and then Okinawa during the final stages of the war.

“We were mopping up the Japanese on the hills and they were sending their kamikazes; we were told to make smoke on the fantail, so they couldn’t see us,” Sperry recalled.

Kamikaze planes would sink 26 allied ships and severely damage another 168 during the months-long Okinawa campaign; of the 12,281 Americans reported killed, 4,907 were naval personnel.

After Japan announced its surrender in August 1945, Sperry’s ship was one of eight minesweepers that swept for mines in Tokyo Bay.

“We spent the night, then the main fleet came the next day and MacArthur signed the peace treaty,” said Sperry. “We swept 83 mines after the war in various ports in Japan. Then we went on a major minesweeping operation in the South China Sea, going back and forth like mowing a lawn.”

Dallas Stephens began his service in Kodiak, Alaska, and went through Landing Craft training under the Marines near San Francisco, before getting aboard an attack transport.

“We were on our way to invade some of the southern islands of Japan,” said Stephens, who served as a Storekeeper Petty Officer First Class from January 1943 until April 1946.

“The war came to an end, so we ended up being dropped off in Okinawa,” said Stephens, who would spend about six months in Japan before being discharged.

He chuckles as he recalled walking around Tokyo with shipmates when they found themselves in the National Diet Building.

“We walked in where all the seats were and, I didn’t mean any disrespect, but I sat briefly on the emperor’s chair,” said Stephens, calling it a youthful adventure. “I tended to be mischievous. I was a young kid, only about 20 years old, so they could overlook my brashness.”

He said he appreciated his role as a supply clerk, adding, “I keep telling everyone, you could always get a bath, you were in charge of the food and the clothing. What more could you ask for?”

Afterward, Stephens obtained a civil engineering degree and became a specialist building nuclear power plants.

“I ended up tied to the U.S. government’s nuclear shoestrings. I was in Iran when the Shah lost his power; we got out of there with good fortune. So, I’ve had a pretty exciting life,” said Stephens. He lived in several countries before retiring as president of Gilbert Commonwealth International.

Erv Terry was a junior in high school in 1943 when he joined the Navy, noting, “I didn’t want to be drafted; I wanted a clean bed and good food.”

As a gunner’s mate third class, he primarily served at sea aboard a destroyer escort, escorting convoys from Pearl Harbor all through the atolls of the Marshall Islands and on to Guam, Saipan and the Philippines, before being discharged in March 1946.

Because of the boat’s smaller size, he said, “when it got rough, it was rough,” and with a grueling watch schedule, “we never had a full night sleep. That’s the way it was. But it was better than fox holes.”

He explained that his job as a pointer was to raise and lower the barrel of the guns, while a trainer positioned it side to side. “Today all the guns are electrical, but we didn’t have that; ours were manually trained.”

He recalled eating mostly reconstituted dehydrated food – one cook prepared three meals a day for 180 men – and taking saltwater showers as fresh was limited. Overall, Terry said, “technically it was a good life; I made the right choice.”

They were escorting a small carrier when the war ended, and to celebrate, he said, “they took the fire hoses and ran them all over the ship, even the officers’ quarters.”

After the war Terry joined the painting and decorating business his father had established in 1908, and which he eventually passed on to his son.

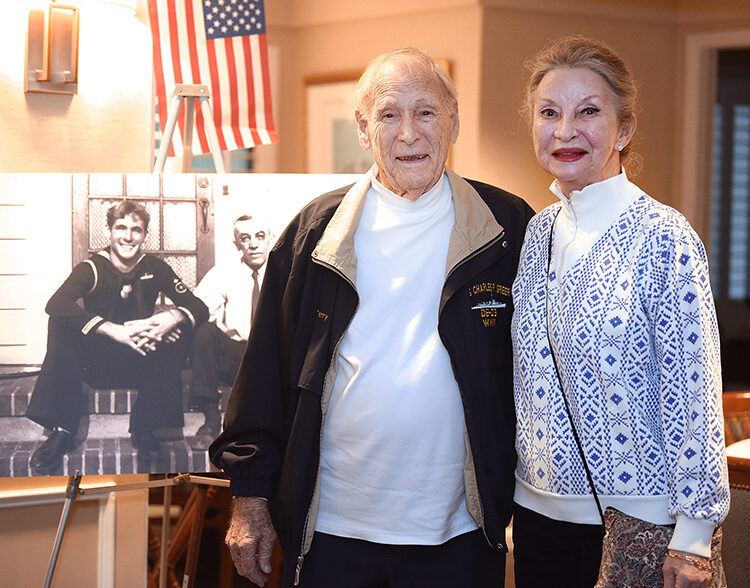

Photos by Brenda Ahearn