If it seems the controversy over the Confederate flag has saturated the nation with reflection over the Civil War, there’s still more ground to cover: next year marks the 150th anniversary of the horrific conflict and the Vero Beach Museum of Art is one of many museums and libraries that are giving space over to the subject.

Opening Saturday at the Vero Beach Museum of Art is a new exhibit called Shadows of History: Photographs of the Civil War. Originally presented by the Corcoran Gallery, now under the auspices of the Morris Museum, the images were acquired over the past decade by Washington attorney and collector Julia Norrell.

Norrell, who goes by Judy, is scheduled to speak at the museum’s members’ reception Oct. 18, as well as at the big-donor Chairman’s Club reception the night before. She is a fascinating woman, daughter of Arkansas state legislators who received much of her early education in a private school in Washington, while still spending summers and holidays riding horses in the rural South.

A lawyer by training, she never practiced and instead went to work as a lobbyist for a diverse list of clients, from arts organizations to machinists to insurance companies. At one point, she served as legislative director of the National League of Women Voters, and played a pivotal role in the fight for Title IX (Joe Paterno was a key opponent). She has called it a high point in her career.

Through it all, she has avidly collected art both folk art and fine art.

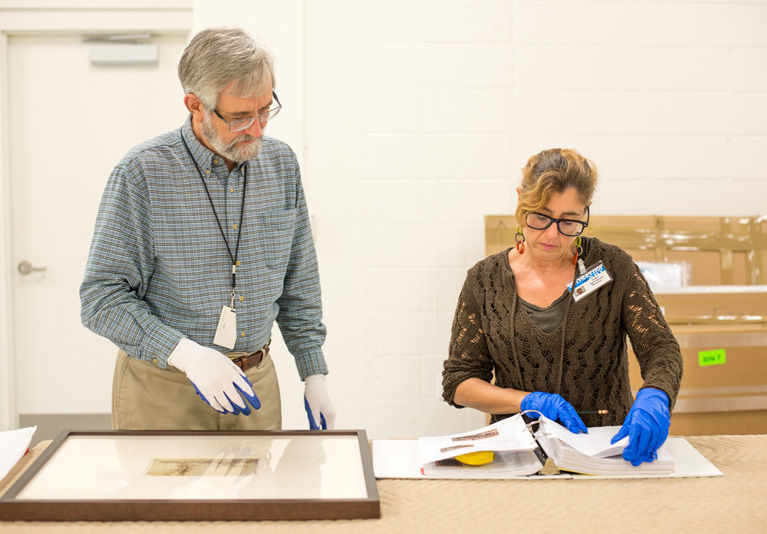

“She grew up with a very broad education and a very broad point of view,” says Jay Williams, who has worked closely with Norrell since 1998, beginning with a touring folk art exhibit they assembled when he was at the McKissick Museum in South Carolina, and later, at the Morris. During his tenure there, the museum acquired 900 of her works.

“She was always interested in delving into the history and finding more out about all these aspects and history.”

It was a copy of Jay Winik’s book “April 1865: The Month That Saved America,” that inspired her to start collecting Civil War photographs. Loaned to her by Morris curator Kevin Grogan who helped assemble the current exhibition, she read the book “on a cold and dismal day while at my farm in Lunenburg County, Virginia,” as she puts it in the foreword to the exhibition’s catalog. She called it “a stunning experience,” one that made her reject the romantic version of “the war I had grown up with.”

“As is true of many Southerners, it took me nearly a lifetime – 70-plus years in my case – to come to terms with the Civil War and its lasting effects.”

Norrell’s breadth of interests may have its genesis in the Fulbright scholarship she won to India. According to a piece in Ohio Wesleyan’s magazine, she switched her application for a Fulbright scholarship to France after ruminating – fuming might be more accurate — over a comment made by her philosophy professor, who was from India, who told her “educated Americans know about Europe, but educated Easterners know both Eastern and Western cultures.” He told her to come back and talk to him once she’d been to India.

In a way, Norrell’s interest in the civil war showed a similar quest for scope. Not only does the exhibit show her interest in the Union and the Confederacy, but in soldiers black and white. The photographs she has managed to acquire of African American Union soldiers are very rare, Williams says. “She was always on the look-out,” he says. “It’s very rare to find African Americans depicted in the war role,” not as cooks or servants, but as soldiers.

Most moving, perhaps, is a photograph, famous but only recently acquired by Norrell, made by a team of photographers known as McPherson and Oliver, who happened to be present when an escaped slave named Gordon made it to the Union line. Presenting himself to Union officers, he asked to join their cause. As the men began to help him out of his wretched clothes and into a Union uniform, they saw the hideous scars of his former masters’ beatings. A wood engraving done of the photograph appeared in Harpers Weekly and from there it “sort of went viral for the 1960s,” says Williams.

Norrell is still collecting. Since the 2012 Corcoran exhibit, some 10 photographs have been added, Williams says.

It also includes a few contemporary works, including three by acclaimed fine art photographer Michael Mergen. He is represented by the J. Fergeson Gallery in Farmville, VA, where he recently relocated and discovered that Union and Confederate soldiers had passed through just days before Lee’s surrender. Soon after his arrival, he set about making rubbings of the often old historical markers along the highway, noting the point of view reflected in their content, and then juxtaposing them in direct-wax rubbings over his large-scale photographs of the landscape as it is today.

Another provocative work is a tableau created by Whitfield Lovell, a sculptural installation that includes a table and a cannonball, and, on reclaimed wood, a life-size drawing in charcoal of a black Civil War soldier. That work is on loan from New York’s DC Moore Gallery for the duration of the exhibit.

For Norrell, the visit to Vero will be her last appearance with the collection. Once the exhibition is taken down in January, it will be shipped home, the end of a three-year tour that included the Corcoran, the Morris, the Ogden Museum in New Orleans and the Cedar Rapids Museum of Art in Iowa.

Many of her folk art works ended up in the collection of the Morris, where Williams worked from 2004 to 2009.

“I’ve arranged for the Folk Art collection of the Morris to be here at the same time as the Civil War photography,” he says.