“In the future, everyone will be world-famous for 15 minutes.”

The Foosaner Art Museum in Melbourne has taken Andy Warhol’s prediction to heart in its current pop art exhibition that includes the chance for visitors to create their own digital pop masterpiece.

The exhibition is divided into three parts. “Pop Art in America” occupies the museum’s east galleries, while “Pop Artists and Friends: Works from the Permanent Collection” fills the west gallery and entrance hall. A small gallery to the right of the main entrance has been transformed into a corner of The Factory, Andy Warhol’s New York City studio, right down to the dull aluminum sheen of its painted vinyl brick walls.

The environment, created especially for the exhibition, is the result of a collaboration between the Foosaner’s curator of exhibitions, Jacqueline Borsanyi; the executive director, Carla Funk; and the curator of education, Sara Russo.

A celling-high stack of Brillo cartons at one end of the gallery (created à la Warhol by local craftsman Jason Reed) forms the outer wall of a photo booth where visitors can pose for a set of four digital photos (these are instantly emailed to the sitter as a souvenir of the experience).

A closed-circuit camera within the booth simultaneously projects real-time pictures of the booth’s occupants on an adjacent gallery wall. A slideshow of previous visitor’s visages – tinted in jarring shades of red, green, yellow and blue— is projected on the opposite end of the gallery. In a nearby corner, beanbag chairs offer a comfy nest to relax and contemplate the hipness of it all.

“Andy did a lot of his portraits from photo booth portraits,” says Borsanyi.

During the mid-‘60s, Warhol also made nearly 500 short 16 mm films (he called them “screen tests”) of The Factory’s notorious habitués as well as its visitors, both the famous and the unknown.

At the Foosaner, both the still photos and the live video are designed to heighten gallery-goers’ appreciation of Warhol’s aesthetic.

“There is that sense of watching. It all relates to waiting for something to happen,” says Borsanyi.

Screenprints by Warhol, including one of his ubiquitous Campbell Soup cans (“Scotch Broth” from the Campbell’s Soup II series of 1969 are on display in Pop Art in America. On loan from the Nova Southeastern University Art Museum Fort Lauderdale, that exhibition also features prints by other stars of the Pop constellation, including Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Robert Indiana, James Rosenquist, Roy Lichtenstein and Larry Rivers.

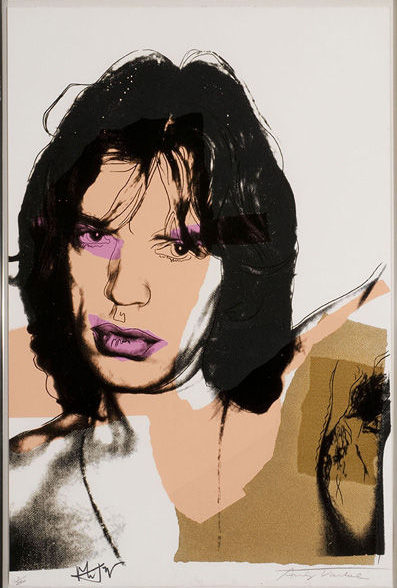

But it is Warhol who steals the show with glamorous portraits of Mick Jagger, Ted Kennedy (silhouetted against a red, white, and blue field of glittering diamond dust) and Mao Tse-tung. The latter, from 1972, is a series of 10 color screenprints of Chairman Mao’s face, each a different vivid hue with contrasting colors for the chairman’s lips, uniform and the picture’s background. The framed prints are hung cheek-to-jowl in two rows of five to form a single artwork. The unit measures over six feet high by nearly 17 feet wide.

Mao’s face was familiar to every American who watched television or read a newspaper during the 1960s and early ‘70s, when news stories detailed the disastrous consequences of China’s Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution. At the time it was considered more than a little cheeky of Warhol to cover American museums’ walls with larger-than-life likenesses of Red China’s leader.

Mao died in 1976. Today schoolchildren and young adults are more likely to be familiar with the graphics of a Campbell’s Soup can than the features of the round-faced, balding Communist.

Borsanyi says that children who have visited the exhibition ask of Warhol’s Mao, “Why are there so many of him?” and “Why is he those colors?”

“We explain to them that artists like to explore different variations on a theme. The color changes reflect the artist’s explorations,” Borsanyi says.

Warhol had another motive in mind. Using the screenprint process, considered a cheap commercial technique for producing throwaway ads and posters, Warhol took as his subject matter soap pad boxes and soup cans, gruesome news photos, and trite head shots of celebrities to provocatively straddle the line between high and low art.

He added unexpected colors to otherwise predictable imagery. By using a crude mechanical process to create his multiple portraits (his assistants executed much of the work), he also thwarted the highbrow belief that a work of fine art is distinguished by the originality and artistic skill of its creator.

“The reason I’m painting this way is that I want to be a machine, and I feel that whatever I do and do machine-like is what I want to do,” Warhol said in a 1963 Art News interview.

A lot has changed since Warhol’s time.

“The children see it differently,” says Borsanyi. “They are more generous about what it means to make art. Even though they don’t know who Mao Tse-tung is, I think that pop has infiltrated the aesthetic of the web. It’s more familiar to them, in many respects, than it is to adults. The repetitious nature of pop feeds into how they see and use technology today.”

Children, Borsanyi notes, “are used to using filters on their digital pictures, and they are used to seeing and changing layers in an instantaneous, electronic way.”

Before the age of the Internet and the personal computer, pop artists seized the moment by appropriating the images of mass communication. Like Warhol’s Mao, this subject matter has often proved to be as ephemeral as melting snow.

The Foosaner’s permanent collection exhibition “Pop Artists and Friends” includes prints from The Peace Portfolio II, a 1972 project organized by artist and poet Patty Mucha to support the cause of the Youth International Party. The “Yippies,” as they were known, were a counterculture, anti-war group who famously threatened to put LSD in Chicago’s municipal water supply during the 1968 Democratic Convention. When the Peace Portfolio was published in a limited edition of 150, it sold for $1,500 with proceeds going to the Yippies.

The screenprints of seven of the eight artists who participated in Peace Portfolio II are represented in the current show: Richard Anuskiewicz, Marisol Escobar, Claes Oldenburg, Robert Rauschenberg, James Rosenquist, Robert Whitman, and Jack Youngerman (missing is “Sketch for World Map” by Oyvind Fahlström).

Perhaps the most striking image in the portfolio is Marisol Escobar’s “Saca La Lengua” (“Stick out your tongue”), an in-your-face depiction of a naturalistically rendered tongue lolling from an open, toothy mouth, with the nose and eyes appearing like a comic afterthought.

Escobar came to New York from Venezuela in 1951 to study painting. She fell under the spell of pop art and appeared in two of Warhol’s films.

“Saca La Lengua” sums up the saucy appeal of pop art, which stuck out its tongue at art world convention and pretention. It created instead something as fleeting as yesterday’s news and enduring as the memory of a kiss.

The Pop Art exhibition at the Foosaner Museum continues through Aug. 30.