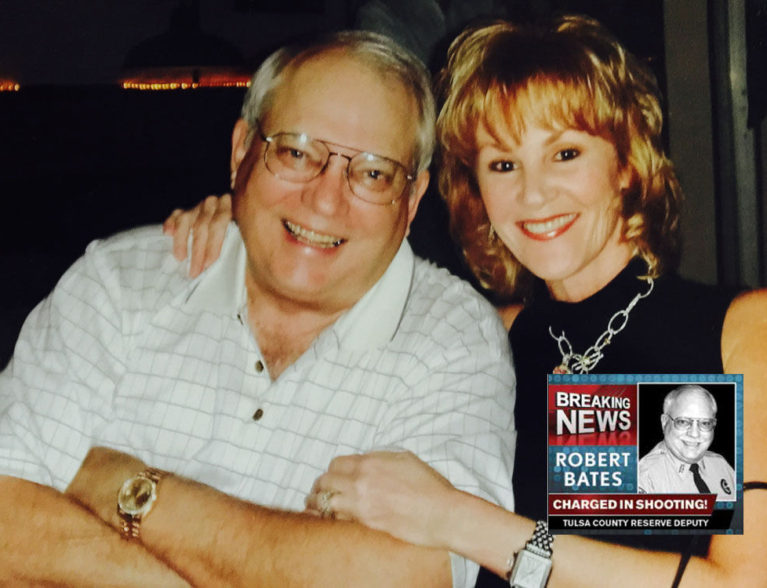

VERO BEACH — As soon as Tulsa, Okla., volunteer reserve deputy Bob Bates shot his Taser at a suspect, the Vero Beach snowbird said he knew something was terribly wrong.

There was so much recoil that the weapon bounced out of his hand to the ground. He knew instantly, he said, that he had fired his revolver by mistake.

Bates, a 73-year-old wealthy white man serving as a pro bono reserve deputy, had shot fleeing African-American suspect Eric Harris, 43, in the back, killing him.

Bates’ action on the morning of April 2 – coming on the heels of a spate of shootings of unarmed black men by white police officers – immediately made national news.

Within days, the part-time Grand Harbor resident, who calls Vero Beach his “favorite place in the world,” was charged with second degree manslaughter.

Reporters from all the major TV networks, as well as reporters from dozens of newspapers, have since been knocking on his door, wanting an interview.

After giving a brief statement with his lawyer on NBC last Friday, in which he apologized to the Harris family, Bates agreed to an exclusive interview with Vero Beach 32963.

“All I can think about – other than how sorry I am that I accidentally took another man’s life, which I would never intend to do – is how much it would help my wife, Charlotte, and me to be able to get away to Vero Beach and be free of the faces peering in our windows all hours of the day and night,” said Bates.

Before the shooting, he had parked two blocks from a police sting, where an undercover cop bought a 9 mm pistol from Harris.

Bates, who as a volunteer reserve deputy usually photographed crime scenes after the fact and sometimes transported arrested people, got involved in apprehending Harris when the previously convicted felon, who had just been told he was under arrest, broke away from police and ran past Bates’ car.

As Harris wrestled to get away from a deputy who had grabbed him, Bates got out of his car and yelled “Taser, Taser,” before shooting, only to realize with horror that he had pulled out his revolver, instead.

“It was the worst moment of my life,” he said.

At a press conference given by the dead man’s family shortly after the shooting, Eric Harris’ brother Andre Harris described Eric as a “fun-loving person who got along with everybody.”

He “paid the price” for past crimes (armed robbery) with prison time, and that shouldn’t work against him, said the brother.

Harris’s only child, Aiden, 16, described his father as a “sweet, forgiving and thoughtful” person, saying that even though his parents were divorced, his father called him every day.

Meanwhile, media questions swirled about the accuracy of Bates’ and the sheriff’s office training claims and whether he had bought his way into being a volunteer cop by donating equipment and money to the sheriff’s office. His attorney, Clark Brewster, said Bates has papers to prove his training and gave them to CNN Sunday.

Further, said the attorney, Bates had quietly given to a number of causes other than law enforcement, including buying shoes for 200 kids at an elementary school in a poor area of west Tulsa and winter coats for the kids a year later.

He also sponsored a little league baseball team and bought uniforms and equipment for a predominantly African-American girls‘ basketball team in west Tulsa.

“His generosity has nothing to do with his buying his way,” said Brewster.

When asked about the good deeds, Bates said, “I try to keep what I do quiet, and I’d prefer not mentioning anything about race when it comes to helping people because it’s irrelevant.”

In Vero Beach, say those who know him, he has also been generous with his time and money to help people.

Bates and Charlotte first came to Vero 22 years ago in December, after he read an article in a travel magazine on Vero Beach.

Following surgery and a discouraging prognosis for advanced prostate cancer, they hoped a vacation home in Vero Beach might lessen Bob’s stress and lengthen his life.

When they got to Vero Beach, they stayed in a Central Beach hotel, since torn down.

“We saw the Christmas parade on the beach while we were in Vero and loved how unassuming and charming it was,” said Bates, who went to Vero Marine Center on Royal Palm the next day and bought a 25-foot Grady White boat.

“Charlotte thought I’d lost my mind because we’d never use it,” he said.

But, within a year, after a few visits, they bought a condo at Grand Harbor and began coming to Vero Beach about three months a year.

At the time, he was an insurance executive, having taken a circuitous route to get there: A graduate of Northeastern University in Oklahoma, majoring in sociology, he began law school at Tulsa University at night, while working as a patrol officer.

But two years into law school, he dropped out.

“I didn’t have the patience to study the details required of a lawyer,” he said. “I’ve always been someone who needs to move around.”

He found that he was especially adept at selling insurance door-to-door and quickly moved up the ranks at a Tulsa insurance company, before starting his own in the 1970s.

By 2000, with a vacation home in Vero Beach, he joined the Citizens Aid Patrol here and worked in the Marine Unit.

“He assisted with getting to boats that needed rescuing and towing and things like that,” said Thomas Raulen, sheriff spokesman.

“It was a great way to be on the water and help people at the same time,” said Bates, an avid boater and fisherman who currently has a 33-foot Grady White berthed here.

Gary Wheeler, who was sheriff when Bates first volunteered here, said that as a volunteer for the Citizens Aid Patrol, Bates was “very helpful on the water and like all of our CAP volunteers was never armed.”

Bates also never contributed to his campaigns, election records show.

And records also show he did not contribute to the campaigns of Roy Raymond, who succeeded Wheeler as Sheriff.

Retired New Jersey detective Phil Weiler, who sometimes talked to Bates about police work while both would be having a drink at the Dockside restaurant on Royal Palm, said he asked him one night in December why he still volunteered in Tulsa with the sheriff’s office.

“He told me it was a good way to help both the victims of crimes as well as the people charged with them,” said Weiler.

“I do try to talk to people who are arrested to get them to think about turning their lives around,” said Bates.

At two restaurants in Vero Beach, Citrus Grillhouse and Dockside, where he and Charlotte often began the evening with a Bacardi and Diet Coke at the bar, he is known to bartenders for low-profile acts of kindness.

They tell of diners and drinkers who work around town in relatively low-paying jobs, often asking for their checks, only to be told that a man who asked not to be identified had paid their bill and left. That man, they say, was Bob Bates.

A bartender at Dockside tells of Bates asking her 8-year-old if she got what she wanted for Christmas this year.

When the little girl, who had dropped by the restaurant with her mother, told him “no,” he gave her $200 on the spot for the iPod she wanted.

A 50-year-old article in The Tulsa Tribune offers some insight into where his inclination to help out may have originated: It describes his mother’s work as an RN and social worker with the public health department in Tulsa.

Her focus, it says, was helping abused children and women, as well as the elderly and “skid row” addicts.

His mother is quoted as saying she never met anyone who didn’t have some good in them, nor anyone who hadn’t taught her something.

“We never knew who’d be having dinner with us because my mother brought everyone home,” said Bates.

Before getting his larger boat several years ago, Bates and Charlotte often took the 25-foot boat, which they kept at the Grand Harbor Marina, to the Keys and the Bahamas.

On one trip about eight years ago, Bob noticed a piece of carpet floating miles off the coast of Islamorada and took the boat closer.

Under the carpet was a young Cuban refugee in an inner tube, who had been floating in the ocean for five days and was extremely dehydrated. Bates got him on his boat, then docked in Islamorada and called an ambulance.

A few hours later, he went to Mariner’s Hospital to check on him and leave contact information.

He and Orlando Justo, who became an economics professor at City University in New York City, have stayed in touch ever since.

Shortly before the shooting, they talked on the phone and Justo told him: “I never forget that I wouldn’t be here without you.”

In the past five years, because of business demands, Bob and Charlotte Bates only spent a few weeks in the winter in Vero Beach, then a week more in the summer.

Last week, neighbors up and down the street in the River Walk neighborhood of Grand Harbor – where the Bates have a spacious house – said they supported him, and knew he felt terrible about what he had done.

“I want to do what I can to help those who were hurt by my mistake heal,” he said in the interview.

On Friday afternoon, Bates’ attorney said he had just received an email from a police officer who had trained the volunteer reserve deputy. Because the trainer is now an undercover cop, his name can’t be divulged.

But the email said:

“I had the honor and pleasure of training Mr. Bates on several occasions. Mr. Bates was one of my best students, and demanded excellence from other members of his unit. I am a 19-year veteran of the Dallas Police Department. My race should not matter, but based on the circumstances of the incident, I wanted to let you know that I am African American.

“I am more than willing to testify as a character witness based on my training interactions with Mr. Bates. Please give him my best, and feel free to contact me anytime.”

Emails like that, said Bates, as well as support from his family and friends – including many in Vero Beach – are what keep him going.

“And,” he adds, “the thought that we may some day be back” in Vero.