Artist Francis Mesaros is a man on a mission. Since 2010, when he emerged from a self-imposed seclusion in his painting studio, the 58-year-old painter has thrown himself into the search for recognition.

By his own account he’s done pretty well, with gallery representation in Florida and New Jersey, sales to wealthy international collectors and a marketing plan that advertises his work in magazines from here to Hong Kong.

“I’ve been blessed. I’m being spoon-fed directions, from God, from the Universe. I mean, there’s so much that’s happening,” says Mesaros.

For those who are not yet familiar with his art, Mesaros’s paintings are thickly impastoed pictures of the ocean: an expanse of glittering sea bounded by a strip of sky at top and no land in sight. A feature exhibit of his work is on display now through May 31 at Gallery 14 in downtown Vero. Appropriately enough, the show is titled “Goin’ Public.”

Gallery 14 assistant Allison Dilliard attests to the artist’s popularity there. “We just sold a piece to someone from Wisconsin,” she says, and adds that a few recent sales to New Jersey came from people who have seen Mesaro’s work on the gallery’s website. Although Mesaro’s prices are the highest in Gallery 14, Dilliard says he is one of its best-selling artists, with prices ranging in the low thousands to $118,000 for a very large seascape called “Eternal Ocean.”

In search of uninterrupted time to concentrate on his work, Mesaros came from New Jersey to a quiet neighborhood in Sebastian in 2009. Determined not merely to refine his technique but also to create an instantly recognizable brand, he painted without a break for 18 months. The result was “Pancture Paintings,” a term Mesaros coined – and trademarked – to describe an artwork that is a painting and a sculpture, all at the same time.

Mesaros’s technique consists of applying dollops of oil paint so thickly to the canvas that they stand in high relief from the surface. The crescent-shaped wedges march in formation from the largest and thickest at the bottom edge of the canvas to the smallest and most delicate applications at the interface between sea and sky. The variables in this painterly formula are two: the placement of the horizon line, which is located anywhere from halfway to three quarters of the way up the canvas, and the colors of the scene. Mesaros has created flaming sunsets, velvety black night scenes and creamy white-on-white confections, but lately his output has been in the turquoise and green hues of a sunlit day on the Caribbean.

Because his paintings appeal to those who love the ocean, since 2011 he has occupied a booth showcasing his art work at boat shows in Miami, Fort Lauderdale and Palm Beach. People at the shows are drawn up short before his work, he says. Leaning forward with glassy-eyed, rapt attention, he imitates a passerby gob-smacked by the sight of one of his paintings.

Mesaros believes so vividly in the uniqueness of his Pancture technique that he says that he is in the process of patenting it along with a special tool he developed to apply the paint to canvas. He says that a second government review of his application will take place this October, and he is optimistic that the patent will be granted.

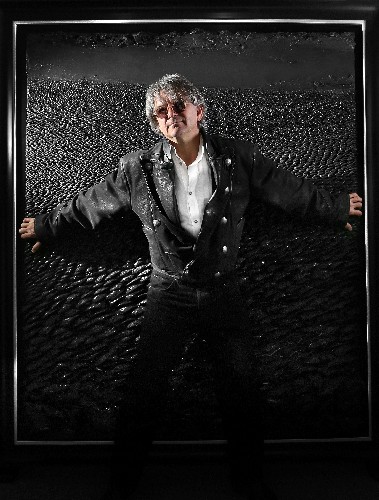

Mesaros is nothing if not optimistic. An attractive man with a boyish demeanor, he loves to tell stories about himself and the people he has met, acting out the part of everyone in his recollected conversations. Enthusiasm pours out of him. He loves life, he loves people, he loves his art, he loves you. He often punctuates his stories with a raucous laugh, and needs little incentive to give his listener a hug.

As one Worth Avenue gallery manager told him, “The way you look, the way you speak – and you’re good looking – darling, you’re going to do very good in this business!”

His exuberance can be a little overwhelming. His conversational thread can change course multiple times during a story, making it hard to follow, or to separate fact from fervor.

“I’ve got – Winston and Strawn is the law firm – listen, you can’t make this stuff up. A billion-dollar, multinational law firm allows a meeting with me,” he says.

With offices across the U.S. and in cities in Europe and Asia, Winston and Strawn represents industry’s heavy hitters. Past clients have included General Electric, Barr Laboratories, American Honda, Microsoft and The New York Stock Exchange.

Mesaros says he was told by one of the firm’s representatives that patenting his technique and painting tool would take two-and-a-half years and cost him $15,000 or $16,000.

“That’s the difference between artists and entrepreneurs: Entrepreneurs are businesspeople, very firm on the ground with what counts. Artists want somebody to wave a magic wand and be discovered as being brilliant,” he says.

Mesaros evidently counts himself among the hard-headed entrepreneurs, albeit one with artistic talent. He decided to go ahead and try for a patent.

Mesaros creates his paintings with palette knives. A tray next to his easel holds a broad assortment of those flexible steel tools, from tiny trowels to spatulas that look like they could lift brownies from a baking pan.

Painting knives are not new. The tool has been around since the time of the ancient Greeks, who fashioned theirs from bronze. Mesaros says that he has developed an improved knife, one with interchangeable blades that will pivot paint onto the canvas in the approved Pancture technique.

He says that he uses a special ground (an underlying surface over which the work will be executed) that gives him the ability to practice “marbling or pancaking, which are techniques that I developed” to blend a pile of pigment directly on the canvas while at the same time creating a sculptural scallop of paint.

Working in thick oil paint has one drawback, he says. It takes up to five weeks for the slow-drying oil to develop a skin that is tough enough to stand the rigors of framing, shipping and exhibition without smearing. That is why, for some of the thickest paintings he has created, Mesaros mixes fast-curing epoxy into his oil colors.

“I have a school, an educational school system, that’s still on my cell phone, that is inquiring when the home kit might be available,” Mesaros says.

He can see it now: “The home kit will be ‘Francis Mesaros Pancture Paints,’ quick-drying Pancture paints, and then it will be the palette knife, and it will be a DVD on how to accomplish a Pancture Painting – a three-dimensional Pancture Painting.”

“With this technique you learn by rote,” he says. “You learn by doing over and over and over again. It also teaches you – this is important; this is the main thing – in order to do a Pancture Painting to the degree that I do it, of course, you have to maintain a consistent enthusiasm.”

For now, though, the kits and Mesaros’ anticipated national promo tour will have to wait on the all-important patent.

And when you have a patent, you have a patent you can sell. If the price is right.

Mesaros confides that a representative of a national art supply company asked him what that price would be.

“I was humble and said, this is something we can talk about,” he says.

In the meantime he’s been thinking about it. He estimates that his patent could be worth millions.

Whether the fickle sisters of fame and fortune are poised on Mesaros’ doorstep is yet to be determined. He is sure of one thing. If you want to make something of yourself, “Work hard. You can achieve your goals too. Work hard. There’s no freebies. Nobody’s gonna give it to you. Work hard. Whatever you don’t know, learn.”