VERO BEACH — John Cullen’s days often start with the whir of a paint-spattered electric pencil sharpener, like a schoolboy settling in for lessons.

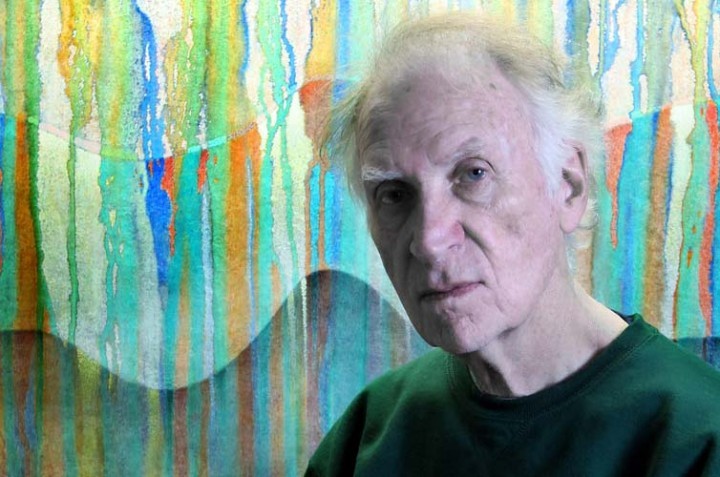

A drawing instructor at the Vero Beach Museum of Art, his own art involves colored pencils, though in a very different technique – he draws over dribbles of paint.

The days that he’s involved in the painting phase start more like a toddler’s, ready to make a mess.

Typically he heads for the back yard, toting his paints along with wood panels taped over with paper. He props the boards in the grass, five or six at a time.

Diluting the paints with water, he starts at the top edge, dribbling colors down the boards. The pigment runs down in squiggles to the bottom edge, and puddles in the grass.

Once the paint is dry, Cullen chooses carefully among the panels to see which speak to him.

“I know within seconds,” he says. “It’s not strictly the flow of color and water. It’s also psychology. A lot of times, I throw them away if it doesn’t have enough juice and magic.”

Those that he keeps end up transformed with his pencils into waves, walls and watery reflections, in a meticulous delineation that overlays the vertical streams of acrylic.

Cullen, who for the last 10 years has taught drawing at the Vero Beach Museum of Art, is about to show his latest works as part of a show at Gallery 14.

His paintings have won first prizes in acrylics and in water color at the Vero Beach Museum’s Art by the Sea exhibition.

He is a frequent entrant in the Bacchus Gallery juried exhibitions in Fort Pierce, and in many exhibitions in New York and Vermont.

Three years ago, he began showing at New York’s Viridian Gallery, a 27-member co-op in Chelsea.

The drawn-over paintings are only Cullen’s most recent technique in a body of work that has ranged from abstracts to very precise drawings of birds.

What intrigues him most is how his new technique provokes his artistic gestures, like moving over a Ouija board.

Armed with his brilliant wax pencils, he brings definition to the dried drips of paint.

“It tells me what to do, in increments, whether to continue with a certain configuration or color,” he says. “It sort of has a grip on me. Each painting tells me how to proceed.”

Between the lines, his mind sees edges form, with depth and direction.

As if the edges cast shadows, he sets about shading them, adding color and blending until a topography of waves develops, an abstraction he says derives of his fascination with water – a fascination born not of Vero’s ocean but of the rivers and creeks of the Adirondacks, near where he and his wife Darlene spend their summers.

It was at a summer camp in those same mountains that Cullen first realized his passion for art. He was 16; a neighbor in New Jersey saw his talent for drawing and found him a place at the art camp with a scholarship.

“I loved it,” he says. “I could never get it out of my system. It just felt perfect. Coming back home on the bus, I was already having withdrawal.”

He managed to go again the following year, and his instructors urged him to think about going to art school. But when it came time to apply college, his father, an agent with the IRS, vehemently objected to him pursuing art as a career.

“If you’re going to go school on my money, you’re going to study business,” his father told him.

It would another 10 years before Cullen finally enrolled at New York University to pursue a degree in fine art. He later earned a master’s degree from Pratt Institute.

In the intervening decade, the 1960s, he got as far away from New Jersey as he could, moving to San Francisco. Taking a few classes at the San Francisco Institute of Art, he worked odd jobs, including driving a cab.

“It was the most fun job of my life,” he says. “You always have a pocketful of cash, and you always have interesting people to talk to.”

Eventually, he returned to New York and at the age of 27, enrolled at NYU. He earned his degree in 1969. A year later, he had his graduate degree from Pratt. Pratt provided him not only with skills; it guaranteed him a teaching certificate, something he knew he would need.

“I knew I did not want to be a commercial artist, I wanted to be a fine artist,” he says. “I liked teaching. There were a lot of problems with it, but it was the only thing I wanted to do that gave me time to do my art.”

He taught high school art briefly in New Jersey, then moved to Syracuse with his wife Darlene and their two young sons. For a while they lived in the Adirondacks; when they went back to visit after retiring to Florida, they immediately began looking at real estate.

They now summer there.

As for Cullen’s classes at the museum, he first approached the education director when he saw how few drawing classes were offered, a critical skill for a beginning artist.

“I’m a very good drawer. I know how to do it and I’ve had years of experience. People here love to paint in water color or oil, but they don’t know how to draw.”

He says his classes have been consistently well attended.

Cullen works seven days a week on his paintings, putting in at minimum three hours a day, often more. In his down time, he plays chess at the public library.