VERO BEACH — In the early days of aviation, the only way to learn to fly an airplane was to fly an airplane. But after falling out of an upside-down open-cockpit plane piloted by a student, fortuitously saved at the last second by a parachute, Albert L. Ueltschi began to wonder if there might be a better way.

That better way ultimately became FlightSafety International.

By the time he passed away last week at his home on Vero’s south beach at the age of 95, the company he founded had progressed from the simple Link trainers of the 1950s to the world’s largest fleet of high-tech flight simulators – and Flying magazine referred to him as the “Father of Modern Aviation Training.”

With 40 sites around the world, including one built at the Vero Beach Airport in 1966, FlightSafety is the official training and retraining school for 17 airplane manufacturers and dozens of commercial carriers, for planes that ranged from single-engine Cessnas to the Concorde.

Every branch of the military has used its services as have 17,000 commercial airline pilots.

Through all his success, Ueltschi retained modest tastes and a great empathy for the poor.

He enjoyed his weekly trip to McDonald’s for an Egg McMuffin and shake. He drove a Ford Taurus with 80,000 miles on it when he was in Vero Beach.

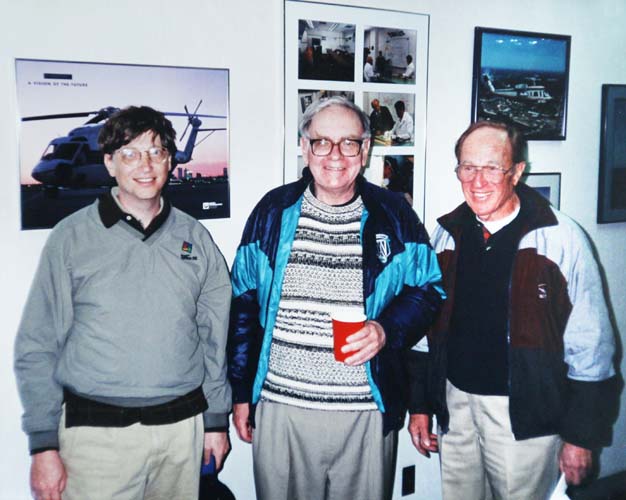

Ueltschi last month signed a “giving pledge,” joining a movement begun by Warren Buffett and Bill and Melinda Gates to have the nation’s most affluent families commit publicly to giving away most of their wealth to charity.

Begun in 1951 at LaGuardia airport, FlightSafety started out training pilots the old-fashioned way – in their planes.

At the time, corporations were adapting World War II military aircraft for executive use. But the pilots they hired had no training on the planes.

Ueltschi filled that niche.

Surviving on his income flying for Pan Am founder Juan Trippe, he reinvested all his profits at FSI, then managed to raise $70,000 through contracts for future training.

With it, he bought a Link trainer, an early flight simulator invented by Edwin Link, who would later design deep sea submersibles at Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute.

By 1966, he was looking to build a training facility for beginning pilots in Florida.

Vero Beach appealed to him largely owing to the presence of Piper Aircraft. It meant he could buy a fleet of Piper planes and have parts and maintenance available next door.

In addition, the city of Vero Beach was willing to sell him acreage at the airport.

He used it to build the dorms that exist today – patterned after the Howard Johnson’s motel on U.S.1. He also built a restaurant for his student pilots, now C.J. Cannon’s.

With Alex MacWilliam’s help, he and his wife, Eileen, found a lot on the south barrier island and built an oceanfront home – his son, Jim Ueltschi, remembers going to bed at night to the sound of dredging at what would become the Moorings across the street.

The hope was that the warm weather would help Eileen’s rheumatoid arthritis. A former PanAm stewardess, she died in 1973. Ueltschi never remarried.

Meanwhile, Jim Ueltschi, who started at FlightSafety as a flight instructor, retired in 1991 as CFO. He and his wife, Jean, live in John’s Island, where his dad had bought a lot for $12,000 in 1970 when virtually nothing was there but a golf course – his sole reason for investing.

Ueltschi took the FlightSafety public in 1968, retaining control of 34 percent of the outstanding common stock.

Growth was huge in the 1970s, and Ueltschi expanded by buying a marine simulator for operators of supertankers.

He had soon signed on 16 companies including Texaco.

The 1980s saw the company expand into military training, and then into the commercial airline market, nailing a contract to train TWA pilots in 1989.

Insurance companies helped business by offering discounts to companies whose pilots updated their training with FSI.

Meanwhile, in Vero Beach, Flight-Safety Academy was training pilots for some of the largest airlines of Africa, Japan, Korea, Switzerland, Australia, and France.

It wasn’t uncommon to see young foreign families from FlightSafety in grocery stores or students in uniform hunched over aviation textbooks in local coffee shops.

So much growth made FSI a target for Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway.

In 1997, the holding company acquired FSI for $1.5 billion in cash and stock, with one proviso: Ueltschi would continue to run it. He did so until he handed operations over to his second-in-command, Bruce Whitman, in 2003.

According to Jim Ueltschi, Whitman nearly sold the Vero property five years ago. With profits in primary training lagging in a bad economy, Whitman had found a buyer, he says.

Employees were notified and a purchase agreement was signed.

But Al Ueltschi stepped in with vehemence.

“My dad was so concerned that he met with the current Vero Beach Airport director to tell him that he did not support the sale,” he says. “My dad seriously considered buying the academy himself. Of course, I would have run it. Anyway, Bruce backed down eventually. My dad loved training the younger generation believing they would be loyal to FSI throughout their careers.”

Today, FlightSafety’s fleet of simulators is the largest in the world and can teach a beginning pilot to fly a 747 without ever stepping in the cockpit, Jim Ueltschi says.

In Vero Beach, that notion was in part to blame for a chain of events in the days following the 9/11 attacks, when the FBI suspected that four students training at FSI were involved in the terror attacks. National media descended on their rented Vero Beach homes as well as FlightSafety Academy.

In an anguished letter to colleagues, Ueltschi offered reassurances and cooperation with the investigation.

“There have been news reports that some who received FlightSafety training were involved. Those reports have so far proved to be erroneous, meanwhile we are vigorously cooperating with authorities to uncover all the facts.”

It seemed the cruelest irony that Ueltschi’s dream of making flying safe could backfire in such a hideous way.

“Totally false,” says Jim Ueltschi. “To this day, some people still believe those erroneous initial reports. It is very hard to unring the bell. It made him even more wary of the press.”

Ueltschi already hated the media for listing his name and net worth, ranked annually by Forbes magazine, and reprinted in the local daily.

His family was wounded that the figures appeared yet again last week in an item on his death.

Though his house near the Moorings had a spectacular view of the ocean, he never changed the carpet or the wallpaper since he built the place in 1968.

He scrupulously watched what he ate, but indulged in a Saturday morning Egg McMuffin with a milkshake, a combo that required careful timing to access both the breakfast menu and the shake machine.

He flew his own plane, a twin-engine Cessna, until the age of 85.

As for ground transportation, he refused to hire a driver – he didn’t want someone to have to sit and wait for him, the way he had waited as Trippe’s pilot.

That experience wasn’t all bad though. Through Trippe’s business meetings, Jim Ueltschi recalls his father befriended his childhood hero Charles Lindbergh, and Wernher von Braun, who ended up visiting the family home.

Until he began living in Vero year-round several years ago, Ueltschi lived in the same small ranch house on seven acres in Greenwich, Conn., that he and his wife had from the time his four kids were small.

The same mowing tractor is parked there, repaired many times by Ueltschi himself.

Mowing was his way of relaxing, his son says. It gave him something to do when people he needed to contact for work weren’t available on weekends, a fact that always seemed to aggravate him.

“He was a guy who wanted to work seven days a week,” said Jim Ueltschi.

At 92, Ueltschi’s license was taken away because he couldn’t hear the clerk at the driver’s license bureau. So he got a learner’s permit and earned it back at driving school, though his instructor warned him that if he slowed to a stop at every intersection he was likely to get hit from behind.

He was so safety-conscious that he couldn’t hand a great-grandbaby over to its mother without a word of caution.

He considered his material success a matter of luck, “being at the right place at the right time,” his son says.

But he worked hard at his main goal in life: Live to be 120.

Since 1981, he rose at 4:30 a.m. no matter where he was to work out to the original Jane Fonda exercise video and got so limber he could sit on the ground and put his knees up to his ears, says Jim Ueltschi’s wife, Jean.

“He was in remarkable shape. He just died of old age,” says Jim Ueltschi.

Raised doing dawn-to-dusk chores on a dairy farm in Kentucky, the grandson of Swiss-German grandparents (his name is pronounced “YULEshee”), he was fascinated by airplanes and earned a pilot’s license at 16.

After teaching flying at various airfields, he got the Pan American Airways job.

In the early 1940s, he was part of PanAm’s ferry operation, flying military aircraft to war zones in Europe and Russia via South America, Africa, and the Middle East.

The planes were often unfamiliar, as were the routes.

“It was very dangerous flying,” says Jim Ueltschi.

For reasons he never knew himself, he was hired as personal pilot by Trippe, who became Ueltschi’s mentor for life.

Though he officially handed over FlightSafety’s reins to Whitman in 2003, he continued to head into the Vero office well into his 90s.

“It invigorated him,” says Jim Ueltschi.

Ueltschi faced grief with a farmer’s equanimity.

In a 12-day span two years ago, two of his three daughters died – one from breast cancer, and while the other sister was caring for her, she was suddenly hit by a rare lung disorder.

Informing his father of the losses was left to Jim Ueltschi.

“It was horrible,” he says. “But when you’re a farmer, you take life as it comes and you don’t dwell on things. When you’ve lived that long, you have a resiliency to deal with reality.”

The couple is deeply immersed in continuing Al Ueltschi’s decades-long charity work with Orbis, treating blindness and diseases of the eye in developing countries.

Going beyond Orbis’ flying eye hospital, they are launching a charity called HelpMeSee, training laypeople on medical simulators similar to the flight simulators that train pilots.

That effort – now with the backing of his father’s friend Bill Gates – would deliver a simple, non-suture cataract procedure to developing nations, curing blindness at a cost of $35 per patient.

“Al Ueltschi made flying safer for all of us,” says Jean Ueltschi, who like her husband Jim will not board a plane unless the pilot has a Flight-Safety proficiency card.

“Safety is the cornerstone upon which business aviation is built, and in a lot of ways Al Ueltschi is the person who laid the cornerstone,” said Ed Bolen, president of the National Business Aviation Association. “He always said that the best safety device in any aircraft is a well trained pilot, and he made sure our community had a lot of well trained pilots.”