For the past year, Vero Beach Museum of Art curator Danielle Johnson has been familiarizing herself with the museum’s permanent collection, which is now over 900 pieces strong. While it is hardly the soup-to-nuts holding of a big city institution, the VBMA collection offers some tasty à la carte dishes, nonetheless.

The result of a sampling she has chosen is on view through Jan. 13 in the Stark and Schumann Galleries: “150 Years of Painting and Sculpture from the Permanent Collection.” It is a satisfying spread.

While Vero museum-goers are used to seeing selections from the collection on view for months at a time in the Stark Gallery, that is not true of the Schumann Gallery. Until now, that gallery has held a summer show, often on loan from someplace else, followed by a different loaned exhibition between Labor Day and the beginning of “season.”

The added space and long run time devoted to “150 Years” is a boon for visitors who want to savor some of the museum’s newest acquisitions, as well as pieces that haven’t been seen much in recent years.

Johnson says that she chose to display representational works from the late 19th through the 20th centuries in the Stark Gallery, and more contemporary ones – in style, as well as date – in the Schumann. She did not hang the artworks within those galleries in chronological order.

“It was more about which pieces looked good and had a nice dialog” with their neighbors, she says.

In the Stark Gallery, for example, Elizabeth Catlett’s semi-abstract onyx sculpture “Triangular Woman” of 1994 glows like a heavenly body against the expansive, crepuscular landscape of Martin Johnson Heade’s 1886 “Duck Hunters in a Twilight Marsh.” (That painting is on loan to the VBMA from the Manoogian Collection.)

Johnson says that, in preparing for her job interview at the VBMA, Elizabeth Catlett was one of the names she planned to suggest regarding future acquisitions. That was before she visited the museum and saw “Triangular Woman” on display.

“I thought, ‘Oh, I won’t be talking about that!’” she says.

She continues, “I do love this piece. Despite the coldness of the material, it’s very touchable.”

In addition to the sculpture’s organic curves, the polished stone’s russet and honey-colored striations, shot through with milky veining, makes this chef-d’œuvre look good enough to eat.

Purchased by the museum in 2016 with funds donated by Mr. and Mrs. Whitney MacMillan, the sculpture honors the tenure of VBMA director emeritus, Lucinda Gedeon.

Speaking of whom, Johnson says that new acquisitions are being shepherded in the same direction that Gedeon and past curator Jay Williams had pointed them: toward works by American and international artists of the late 19th century to today.

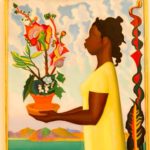

In addition to Catlett, an American-born artist of international reputation, there are four other women represented in this gallery, including Isabel Bishop, whose “Hearn’s Department Store – 14th Street Shoppers” of 1927 has the classical composure of a Greek frieze; Heloise Crista, with a bronze family group, “Archetype” of 1988-89 that recalls the streamlined aesthetic of the 1920s; Liselotte Moser, with an enigmatic 1964 portrait, “Gretchen”; and Marguerite Zorach, whose magical “The Golden Orb” of 1921 entered the collection just this year.

“We have more men than women in the collection,” says Johnson.

That is not surprising. Large or small, in almost every museum in the country, art works by men make up the lion’s share of the permanent collection.

“It is something that I would like to be more conscious of in the future,” she adds.

A heady whiff of testosterone in the Stark Gallery can be traced to a 1936 painting by Waldo Peirce that holds pride of place on the back wall. “Hemingway, Dos Passos, and Waldo Peirce, Dry Tortugas, 1929” presents a movie-star handsome Ernest Hemingway lounging with John Dos Passos in an open-air shed. Dos Passos is shown tipping a bottle toward Papa’s proffered cup as Peirce, sitting on the dock outside, points a pistol toward stage left. A view of Fort Jefferson forms the backdrop for the scene.

A 2017 gift of William D. Hammill and family (who, notes Johnson, have presented three other works by Peirce to the VBMA). this painting of Hemingway et al. is a fascinating glimpse of Florida history.

In the Schumann Gallery, Jim Dine’s 9-foot-square bathrobe painting “The Red March Forward” of 2005 vies for breathing room with the other abstract works on display. Hung adjacent to it, Joan Snyder’s untitled 1973 painting is a much smaller work. While it does not exactly play David to Dine’s Goliath, it handily holds its own in comparison. In addition to sharing a palette of colors, the two paintings both display formal compositions that have been deconstructed by their artists’ expressive paint handling.

Artistically speaking, Jim Dine first used a bathrobe as a stand-in for himself in 1964; since then it has appeared in scores of his prints and paintings. Although the colors and textures he uses to present the motif vary from piece to piece, Dine’s basic composition does not change. The robe is presented in a symmetrical composition that fills the frame. Invariably, a knotted sash is cinched around its middle, and its empty sleeves are placed jauntily akimbo.

“The Red March Forward” features long paint runs that descend from the sleeves’ edges and the lower edge of the robe’s sash to the bottom of the canvas. The cascading paint can be read as fringe on the garment; it might also suggest water falling from the robe, like mountain cataracts in a classical Chinese landscape.

Because Dine is associated with the Pop Art movement that superseded Abstract Expressionism in the early 1960s, his “Red March” might also represent a jokey jab at art history. He is said to have painted his first bathrobe after seeing one illustrated in a print ad. Here, the mundane symbol is executed in the expressionist manner of an action painting, where messy drips, as the product of the painter’s process, were not only tolerated but expected.

Joan Snyder’s 1973 work continues a series she started four years earlier with a painting titled “Lines and Strokes.” The VBMA’s work was created during a time of change in the series, when Snyder was beginning to personalize her loosely constructed grid paintings with private symbolism that made reference to feminism in general, and to female genitalia in particular.

For those who prefer something that elides the gender gap, Patrick Archer’s mixed media work, “Fleur et Klee” of 2000, is it.

“The most obvious reference to Klee would be right here,” says Johnson, pointing out a small photo-reproduction collaged to the canvas. It is a detail of Klee’s 1937 “Harbor with Sailing Boats.”

Johnson explains that Archer’s colors and his use of sgraffito (scratched-through) layers of paint also pay homage to Klee.

“I like the fact that in this work you do have these obvious references to a famous predecessor, yet at the same time, it’s unique,” says Johnson, who remarks on the variety of subtle textures Archer has used in his picture.

“Every time I look at it, I see something different,” she says.