A new exhibition at the Vero Beach Museum of Art – A Tangled Plot: Works by Annie Blazejack and Geddes Levenson – introduces complex, interwoven storylines, replete with layers of hidden elements, symbols and symbolism. The exhibit of 42 works, created collaboratively by the two women, is on view through Oct. 5.

“The show is really a celebration of the natural world and this push and pull with humans and nature. I would say their works are extremely layered with influences,” says Caitlin Swindell, VBMA senior curator.

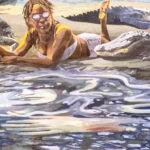

“The exhibition starts with the Metamorphosis section, which generally features these hybrid alligator women figures. This idea of transformation in nature; this surreal sci-fi element,” says Swindell.

Next is Setting the Stage, a plant and animal narrative mostly absent of the human figure that winds its way through the exhibit’s “tangled plot.”

“The final section, Unreliable Narrators, features all female figures, contorted in different poses, echoing things from nature, and engaging with nature in unexpected ways,” says Swindell.

Lifelong friends, Blazejack and Levenson both attended Brown University, and received MFAs from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts/Tufts University (Blazejack) and Pratt Institute (Levenson). They describe their collaborative process as fluid, taking turns on various artworks and, as Levenson says, egging each other on.

Their use of anamorphic projection causes viewers to pause in order to fully comprehend what they’re seeing.

“Which is important because the stats on people in museums is that they often breeze by super quickly. I feel like these are getting people to really unpack and look closely,” says Swindell.

In “Swamp Reclaims the Pool 2018,” two worlds combine as three hybrid alligator women swim in clear water that transitions into vegetated water.

“Right now, our human spaces and wilderness are as separate as they can possibly be. And soon, in the future, it will be like our swimming pools will not be crystal clear. They’ll be habitats. And we, to continue living well with the wilderness, will adapt,” Blazejack says.

“Really radically,” adds Levenson with a laugh.

Some of the works stemmed from an Artists in Residence program they completed in the Everglades.

“They’re so staggeringly magical and beautiful, but you really have to get in them. From far away it’s kind of flat and brown. But once you get knee deep in the water and you’re looking around you, it’s just the most magical place in the whole world,” says Levenson.

“We would go out in the morning and explore. They had all these amazing experts in water management and birds and everything and we got to go python hunting,” she adds.

Hence “Another Sexy Highway 2019,” an oil on canvas that includes a coiled 25-foot fabric snake.

Other works, including a couple of stilted dioramas, highlight the crucial role of mangroves, whose prop roots seemingly walk on water.

“We had this show all about ‘Macbeth,’ and there’s this moment where the witches say something like Macbeth shall not be vanquished until the forest walks. And Macbeth is like, sweet, the forest doesn’t walk. But in the Everglades, it does,” says Blazejack.

Newer pieces were made using a laborious but effective process of painting neon parts first, covering those with tape, painting the rest, and removing the tape.

In “The Lurker, 2024” the viewer’s eye is initially drawn to its vibrancy and a little ceramic snail perched at the top, before noticing a set of eyes peering out.

“Another exciting way to approach the show is the idea of the gaze, how you catch figures looking out at you. You’re caught off guard with what you’re seeing,” says Swindell.

“We like throwing in a lot of distractions,” Levenson admits.

Referencing “We’ll Be Wiped Out, Darling 2024,” where a lounging woman roasts a marshmallow over lava, Blazejack says it’s their version of a reclining woman.

“We called her pose the Power Lounge. Like she’s reclining so hard that she’s sort of dripping off of the furniture,” says Blazejack.

Tiny ceramic hatchlings dot the wall beside “Don’t Stop Me Now, 2023,” where a kneeling woman amassing large rocks attempts to gather in the moon.

“She’s taking that, too. But then the sea turtles are attached to it, because they follow the moon,” Blazejack explains.

“Night Garden, 2024,” which they say has the show’s most villainous character, sees a woman shoveling into the dirt, below which is home to a variety of animals.

“My experience with gardening is that it’s actually an incredibly violent thing, where you’re like killing one plant to make room for another, and I decide. Of course I love gardening, but I also want to be honest about what I’m doing,” says Levenson.

“I love this because I feel like it encapsulates a lot of the show; this push and pull between nature and humans,” says Swindell.

“She’s looking at us like she’s got this, but she’s about to spear through and the snake is at the ready. So who’s going to win in that fight? And these peaceful animals that are potentially next in line. But then you have the eggs, which is signifying, potentially, no matter what happens, life’s going to move forward. It’s just so dynamic, all the little layers,” she adds.

The double entendre of “You Have Such a Soft Belly (2023)” can refer either to the woman describing the feathery belly of the vulture or the vulture seeing the woman’s soft belly as something to feast on. A tiny hole is drilled into the bottom right vulture’s eye.

“When we first showed this painting, we built a false wall in the gallery so that you could walk behind the painting and you could peek out into the gallery,” says Blazejack.

“It was a show all about the gaze, and you’re suddenly like, A: I’m really creepy; B: someone else has maybe been watching me this whole time; and C: that was the anamorphic perspective for Medusa, which is notoriously dangerous,” adds Levenson.

The center of the exhibition features two flood preparedness installations created for show in Durham, N.C., where a predicted sea level rise tideline was drawn on the wall. The paintings are hoisted by coiled ropes attached to pullies they crafted.

“We liked that sort of jokey idea that this painting is now a better investment because in case of flooding, you can pull it up and evacuate,” Blazejack explains.

“I think people often don’t know that you’re allowed to laugh at a painting. So because we’re dealing with something as heavy as climate change, we want people to be able to laugh and feel OK,” says Levenson.

“That’s a benefit of collaboration. I think a lone painter in her studio, taking herself very seriously, might have more trouble making funny work,” says Blazejack.

For more information, visit VBMuseum.org.

Photos by Joshua Kodis