Sitting around the kitchen table, the Idlettes say a prayer before feasting on sizzling steak, fresh mashed potatoes, tasty green beans and succulent pecan pie. Laughter and joy radiate inside the Idlette household nestled along a quiet residential street that runs through the close-knit Gifford community.

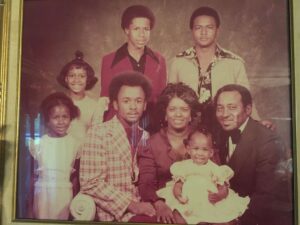

From left to right: Keith, Jacqueline, Jennifer, Joe Jr., Bernice, Jody and Joe Idlette III. PHOTO PROVIDED

It’s a typical Sunday after church for the Idlettes, considered one of the pioneer families of Indian River County. While reminiscing about the struggles for civil rights, along with the victories in making the front-porch town better, the Idlettes come back to the mutual understanding that the most important thing they have…is each other.

“I thank God every day for giving me a beautiful family,” said Joe Idlette Jr., who at 91 is the patriarch of the family. “I’m responsible for my children, their character and well-being. I set the standard for them by being a good example. My goal is to please God with the task he gave me of raising them,” said Idlette, married to his wife Bernice for 71 years.

The passing of time has not faded the impact of the stories. The Idlettes – who attend Mount Zion AME church in Gifford – have watched the ebb and flow of history, through the nation’s good and bad seasons.

The couple says relying on a higher power will give guidance in the roughest of social storms.

“Try to please God if you want to be blessed in this life,” said Bernice Idlette, who had a longtime career as a cosmetologist. “Treat others how you would want to be treated. Show love for one another.”

A Calling

The couple also put an emphasis on public service.

Joe Idlette, who served two years in the Korean War, returned to Vero Beach 10 years after the Brown v. Board of Education lawsuit in 1954 delivered a blow to segregated schools, sending a culture shock through the nation.

The ruling determined segregation in school – dubbed ‘separate but equal’ education for Blacks and whites – was unconstitutional.

Family portrait of the Idlette family. PHOTO PROVIDED

But seeing that there was no sign of change in the segregated local schools, Idlette answered the call for change and sued the School District of Indian River County in 1964. Then came the reports of Idlette becoming a target of the Ku Klux Klan.

Five years later, Idlette’s children, along with other Black youth across the small, rural county, would be among the first to attend the once forbidden, all-white schools. Today, the Idlette family tree extends down to six children – Anthony, Joe III, Keith, Jacqueline, Jennifer and Jody – along with 10 grandchildren and 12 great-grandchildren. All were taught to rely on God and to speak out when needed.

“My mother and father blessed me with great siblings. I wouldn’t trade them for anything in the world,” said Idlette’s oldest son Anthony Idlette, who along with his brother Joe Idlette III were part of the first integrated class to attend Vero Beach High School. “I know for a fact that if I needed anything I could go to any one of them.”

Moving South

The Idlette family’s early roots trail north to Georgia, where their ancestors were slaves, then free men and women and sharecroppers.

The storied family even has a connection to the late President Jimmy Carter. Rachel Idlette Holt Clark, born April 2, 1890 in Sumter County, Georgia, and her husband Jack helped raise a young Carter at their house on a farm in Archery, an unincorporated community in Webster County.

Carter – who later became governor before being elected president in 1976 – mentions Clark in his book “An Hour Before Daylight.” The passage reads, “Of all the people who lived near us on the farm, Rachel Clark was the most remarkable and made the most significant and lasting impact on me,” according to an article from the National Park Service.

Clark would enlighten Carter about life lessons and provide him wisdom. Generations after Clark, Joe Idlette instilled values of education and leadership in his own children.

“We were strongly rooted in education. Education was everything in our family,” said Jennifer Idlette, the second-youngest child of Idlette, whose calling led her to become a principal and assistant principal at local schools. She is now the director of transportation for the School District of Indian River County. “There was a high level of expectation and accountability.”

Jody Idlette (left) with TRIO Upward Bound students at a brain bowl competition July 2024 in Indian River County. PHOTO BY NICK SAMUEL

Jody Idlette, the youngest child of Idlette, said the siblings were required to bring all of their school books home every day. Jody Idlette said they were expected to make the honor roll, sit and behave in the classroom.

“We were going to be quizzed every night,” said Jody Idlette, who later served as principal and assistant principal at county schools and is now the director for the local TRIO Upward Bound college readiness program. “It didn’t matter if you had good grades. You also had to worry about comments on the report card. Even if you had straight ‘A’s,’ if you had a ‘tardy’ you were in trouble. If you had ‘talkative,’ you were in trouble.’”

Public Service

In 1974, after battling for desegregation, Joe Idlette became the first Black school board member for Indian River County, a role he would serve in for 20 years. Idlette, who worked as a classified document carrier with Pan Am at Patrick Air Force Base, was also school board chairman for 12 years.

Joe Idlette III, the second-oldest sibling who would follow in his father’s footsteps of community activism and later become president of the Progressive Civic League of Gifford, said he listened to Idlette’s conversations with Bernice about the school board.

“I observed him through his work and volunteerism,” said Joe Idlette III, who has been president of the Progressive Civic League of Gifford since 2004. “That affected me to the point where I got involved and am still involved today.”

Courage in the face of danger

Like many others in the Civil Rights-era generation, Idlette stepped outside of his comfort zone and into a leadership role to improve the quality of education for Black youth in the county. It was a perilous time for anyone who sought to advance the rights of Black people.

“There were several situations where Black people were killed by anti-Black folks because we were trying to evolve in society,” Idlette said. “My wife never questioned my decision about trying to get my kids into integrated schools. She never showed me she was fearful. She was always there…young and beautiful.”

Over a decade before in north Brevard County, the activist couple Harry and Harriette Moore were killed by the Ku Klux Klan. The pair raised their daughters while registering Black people to vote and advocated for equal pay for Black teachers. On Christmas night in 1951, a bomb exploded under their bedroom. Harry died on the way to the hospital, while Harriette died in the hospital nine days later.

Marching on in spirit while singing the sweet hymns their ancestors once sang in small churches, not even death could stop the mission entrusted to Florida’s Black activists like the Moores. Many, history shows, understood that change was needed for a better life down the road.

But the shadow of death remained a reality.

Joe Idlette Jr. with his wife Bernice. PHOTO BY NICK SAMUEL

Despite reports of death threats from the Ku Klux Klan, Idlette, with his wife Bernice Idlette at his side, charged on a duty to desegregate schools within Indian River County.

“The FBI said they needed to talk with me. They told me I was on the list of the KKK and that it was a possibility they would try to kill me. I had threats on the life of my family while we were involved with the suit,” Idlette said. “(The agent) asked me if I had any identifying spots on my body if (the KKK) were successful. He assured me they thought they had it under control and there was no danger.”

Idlette sued the School District of Indian River County in 1964. The school district was placed under a desegregation order in 1967. Public school children from all backgrounds became desegregated by 1969.

“The only way I could sue is because I had the ear of the local NAACP. I didn’t have the money to do that myself. The NAACP sent lawyers to represent me and my case. They did the job,” Idlette said. “The suit still has not been fully settled. All the elements of the desegregation order have not been fulfilled. That’s a long time for people to fool around.”

Six decades later, some of the remaining issues under the order include access to transportation, access to extracurricular activities and the hiring of more Black teachers.

Idlette said it is important to have people in authority with initiative and a desire to see positive community change.

“If you’re willing to accept things the way they are, you’ll always have to accept things as they are unless there’s someone who has the capability and desire to initiate change,” said Idlette, a 1953 Gifford High School graduate. “I often hear people say ‘somebody needs to do this.’ Then I say, ‘well who is somebody? Is that me, is it you?’”

Separate but not equal

In 1923, Idlette’s father, Idlette Sr., moved from Georgia countryside to the sun-splashed orange groves of Indian River County, where he met his wife Nancy. Like many of his peers, as a child Idlette Jr. had to briefly stop attending school in Indian River County to help his father work in the citrus grove to support his family.

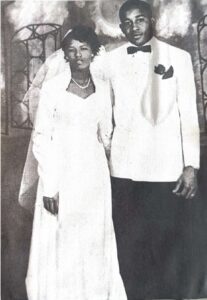

Bernice Idlette with Joe Idlette Jr. in a 1954 wedding photo taken in Vero Beach. PHOTO PROVIDED

This caused Idlette to fall behind one grade in school.

“The Black schools were not compatible to white schools. We had a library with six books and no rigorous courses,” Idlette said of the Jim Crow-era conditions that legalized racial segregation. “We had to walk to school. Lesson plans were different.”

Idlette met Bernice Idlette at Gifford High School. Idlette was the first quarterback for the football team. Bernice Idlette was homecoming queen during her time at the school, originally located on 39th Street east of U.S. 1 and adorned with the maroon and white school colors.

“I was the only one who could get (Bernice’s) attention,” Idlette said. “She had an appeal to me.”

After schools were integrated, the shiny sports trophies along with other memorabilia from the campus ended up discarded. Even with integration, Black people were still not fully accepted in society.

Vero Beach, a quiet but growing beachside town far removed from bustling cities like Orlando or Miami, operated as a sundown town. Similarly, predominantly white communities dotted the southern U.S., making it known through police harassment, even signs that Black residents were not welcome after dark.

“The bell rang before dark and Black people had to be out of town,” Idlette said. “The police’s job was to keep Black people in their place. If we were walking and they felt like we didn’t need to be there, they would pick us up and sometimes take us to jail. Police still think that’s their job.”

Black people were prohibited from trying on clothes at retail stores. The Idlettes said that Black people also had to enter through the back entrance of businesses to receive service. Brown vs. Board was the first crack in the social structure of segregation. The Civil Rights Acts of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965 would further erode the legal structure of Jim Crow.

Leading the school board

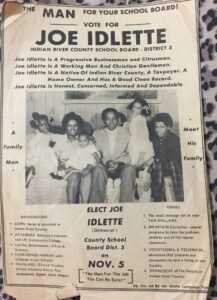

A flyer announcing Joe Idlette Jr.’s candidacy for the School District of Indian River County. PHOTO PROVIDED

Idlette emphasized that building trust and confidence in fellow school board members, along with the community, is key for anyone aspiring to run for and maintain such a position. Idlette, who successfully ran as a Democrat, said it’s hard for Black people to get elected because Indian River is a conservative, Republican county.

“It has to come to a point where they don’t see you as just a Black person, but a person with an idea that can be good,” Idlette said. “When you get on the board, you have to have reasonable questions and answers.”

Idlette said school board members help develop the policy of the school system. The school board only has authority when they act as a board member, not individually, Idlette said.

“People have to want to hear what you have to say. Other than that, you get ignored,” Idlette said. “If you can convince people that you’re genuine and what you’re saying can be meaningful, then folks are willing to listen to you and hear what you have to say.”

Next generation

Tristen Idlette, one of Idlette’s 10 grandchildren, was the first grandson to graduate from college. Tristen Idlette said the traits of hard work, dedication and faith instilled in him by his grandparents motivated him to graduate with a bachelor’s degree in business administration in 2017 from Florida Southern College in Lakeland.

“I think education has trickled down to my generation. My cousins and I wanted to follow in the footsteps of our grandparents, aunts and uncles,” said Tristen Idlette, who regularly speaks with teenagers at the local chapter of TRIO Upward Bound about his college experience and continuing their education. “Being in my mother’s classroom at a young age was something that was always viable to me. It’s important not only to understand education and where I come from, but also to spread the wisdom and knowledge that I get from my grandparents, mother, aunts and uncles.”

But the family value of advocacy continues.

Tristen Idlette reads to a group of children during an event hosted by the “Renaissance Man” nonprofit organization in Dallas. PHOTO PROVIDED

Tristen Idlette previously lived in Dallas, where he served as director of collaboration and communication for Renaissance Man, a nonprofit focused on bridging the gap between young Black men and boys and mental health by providing free haircuts, counseling and reading sessions.

As the third-youngest grandchild, Tristen Idlette, who moved back to Vero Beach in September, is eager to make an enduring impact in the community.

Tristen Idlette said anytime he felt discouraged, his grandparents would share a Bible passage that had a life lesson. Tristen Idlette reflects on Joe and Bernice Idlette, and how their sacrifices and dedication helped shape his future.

“They taught me if you keep the faith and put God first, then everything will be okay.”