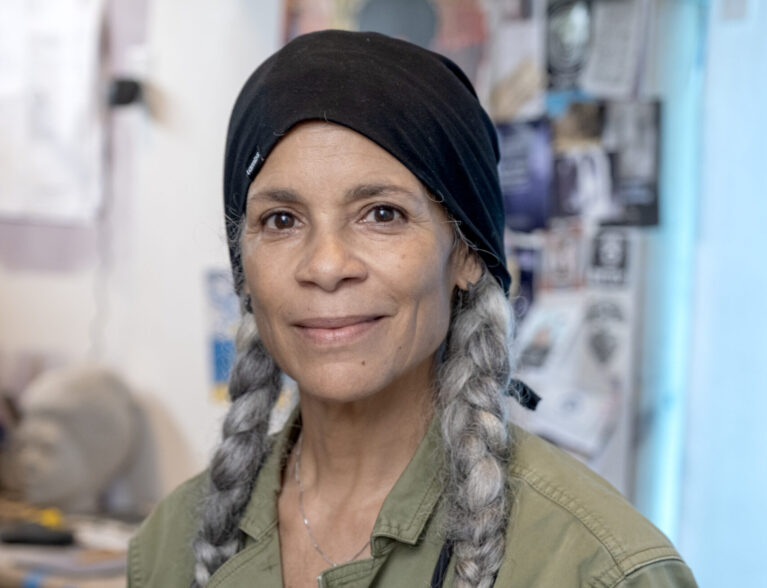

In 2012, after retiring from a remarkable 25-year career in broadcast journalism, Dana King embarked on a quest to give voice to the legacy of extraordinary African Americans through her figurative sculpture works, Black Bodies in Bronze.

King could have rested on her laurels, having earned five Emmys, two Edward R. Murrow Awards and two Gracie Awards for her work as a news journalist in war-torn countries, but instead is creating permanent monuments to the contributions, resilience and bravery of Americans of African descent.

“Representation matters; I think it’s really important that people know the truth of American history,” says King, who moved to Vero from Oakland with husband Clay nearly two years ago, following in the footsteps of her daughter, son-in-law and grandson.

A product of the Midwest, King was born in Cleveland and earned a bachelor’s degree from Ferris State University in Michigan. After moving to Los Angeles, she worked in ad sales at KNBC and KABC and, despite a lack of on-air experience, was unexpectedly tapped to become a reporter.

“At the No. 1 station in the No. 2 market. I don’t recommend it,” says King.

“I mean, it was trial by fire. My goal was just not to embarrass my colleagues who had worked their whole careers to get there.”

She would eventually anchor the CBS station KPIX-TV in San Francisco before retiring.

“The business actually left me. I wouldn’t dye my hair,” King recalls. “It’s hard for women in that business.”

King had already begun to appease her artistic side by pursuing an MFA from the Academy of Art University in San Francisco when her life was altered by a weekend course with sculptor Philippe Faraut.

“And that was it. I fell in love. It was just a weekend course, but I had learned so much that I just wanted to go do it. I’ve been doing it ever since.”

When the Thelma Harris Art Gallery in Oakland took a chance on her early on, choosing and selling all of her works in one show, she began earning public art commissions.

Her first, depicting civic leader William Byron Rumford, stands in South Berkeley.

“He was the very first African American elected official from Northern California in the state legislature. He wrote the Fair Housing Act for California that then got rolled into the ’64 Civil Rights Act,” says King.

Although she had completed many busts, this was her first life-sized piece.

“I didn’t know what I was doing. And so I went to Home Depot, kid you not, and I bought these big plumbing parts, and I built an armature with plumbing parts. As soon as the mold was made, it just collapsed onto the floor,” King recalls with a laugh.

“But he’s my very first sculpture and I love him,” says King.

“I do consider the work to be subversive, because I take a form of style, which is classical, figurative sculpture, and I take a material, bronze, that is normally used to elevate Eurocentric individuals, and I use it to elevate African descendants. And until they’re out there to the degree that Eurocentric sculptures are out there, then it’s subversive.”

Among the sculptures situated throughout the country:

• “Guided by Justice,” a three-piece sculpture at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Ala., representing women of the Montgomery Bus Boycott;

• Huey P. Newton, activist and Black Panther founder, in Oakland;

• Joseph Thomas Gier, engineer, inventor and tenured professor, at Cal-Berkeley;

• Ida B. Wells, trailblazing investigative journalist, activist and suffragist, at Columbia University;

• William Lanson, prominent 19th century entrepreneur, abolitionist and civil rights advocate, in New Haven, Conn.

• Civil rights activist Ella Baker, a work in progress, is slated for Ohio State University.

“She helped start the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and was instrumental in the support of the sit-ins at lunch counters. She was super brave,” says King of Baker.

Toni Stone, the first woman to play in Major League Baseball, was commissioned by the San Francisco Giants, and will be installed this September.

“She played in the Negro Leagues in the late ’40s and early ’50s and she was a badass. She made her way onto teams and played with and against men,” says King. “And now that Major League Baseball recognizes the Negro Leagues, her stats are official.”

A bust of Tyrone Carney, a young soldier killed in Vietnam, will include a base digitally mastered to tell his story.

“His family and the community where he grew up had been working for 20 years to get a sculpture of him,” says King. “He was a religious young man, and he had just graduated high school and so it will tell the story of his life.”

She utilizes the lost-wax casting process that harkens back to ancient times, but also takes advantage of modern technology.

“There’s a lot of moving parts, and while I am familiar with every aspect of it, I don’t do every aspect of it. It’s an incredible process and I’ve only recently become able to use the new digital aspects. It cuts out a lot of weight and time,” she explains.

“There are two ways to create a sculpture. You can build an armature, which is like the skeleton, and then you pack clay onto it, and then you create it. And that weighs hundreds of pounds. Or you can build a maquette, which is a replica of the sculpture, 18-inches to 24-inches or 36-inches,” says King.

The maquette is then digitized, and 3-D printed in a dense foam that can be carved and cut, which she then covers with an oil-based clay to sculpt.

The mold process takes place at the foundry, during which she is given one last chance to approve the wax replica.

“And then once that is finished, another mold is formed over the wax, they pour the molten bronze liquid into that mold, and the wax squirts out the sides and seals it off. The foundry does all of the heavy lifting, from the mold making to the installation. And so, if it takes me six months, it takes them six months,” says King. Her last step is applying the patina.

“My work is my love letter to Black people. And it’s not a revolutionary act. It’s really just what I’ve been gifted to be able to do,” says King.

“I don’t care to have my work in museums; I want people to access this work for nothing, and to learn from it, and learn more about themselves.”

Photos by Joshua Kodis

- Dana King PHOTO BY JOSHUA KODIS

- Dana King PHOTO BY JOSHUA KODIS

- Dana King PHOTO BY JOSHUA KODIS

- PHOTO BY JOSHUA KODIS

- PHOTO BY JOSHUA KODIS

- PHOTO BY JOSHUA KODIS

- PHOTO BY JOSHUA KODIS

- PHOTO PROVIDED

- PHOTO PROVIDED

- PHOTO PROVIDED

- PHOTO PROVIDED

- PHOTO PROVIDED

- PHOTO PROVIDED

- PHOTO PROVIDED