Rock ‘N’ Roll Billboards of the Sunset Strip: Photographs by Robert Landau, on display at the Vero Beach Museum of Art, is a fascinating pictorial history of some of the elaborately designed and hand-painted billboards that promoted burgeoning recording artists during the late 1960s and 1970s.

“It’s an art form that’s not really in existence anymore. It’s obsolete; it’s gone,” says Caitlin Swindell, VBMA chief curator, explaining that signage is now digitally created.

In many cases, Landau’s photographs are the only record of their existence. The billboards, which could take up to 10 days to create, were often up for only a brief time before they were dismantled and painted over. By the 1980s, MTV entered the fray and the money previously spent on billboards was diverted to making music videos.

Living in an apartment above Tower Records, Landau was in the right place at the right time for his visual odyssey, which began at age 16.

“I saw the Beatles billboard and I loved the Beatles, so I took a picture. Since I lived a block from the Strip, I’d see these guys early in the morning installing them all; putting this one up and taking another one down,” he explains.

“And I realized that if I didn’t take a picture they might vanish. So, whenever I saw one, I’d get a picture, not knowing if it would be there long or not. They were very transient art forms; they came and went.”

It wasn’t until some 40 years later that he realized the true significance of what he had, prompting its compilation into his book, “Rock ‘N’ Roll Billboards of the Sunset Strip.”

“I was just a fan. It was actually a pretty interesting period in history. A rock and roll that very few people know about,” says Landau.

To provide historical context, the exhibit includes a selection of early billboard-related photographs, including ‘The Louisville Flood,’ a powerful 1937 shot by Life magazine photojournalist Margaret Bourke-White.

In it, Black victims of that disaster are seen lined up to receive emergency resources. In stark contrast, a billboard behind them features a carefree White family in a car and the slogan: ‘World’s Highest Standard of Living. There’s no Way like the American Way.’

“That’s what I love about the photographs; there are so many components,” says Swindell, referencing such elements as the photographer, the subject, its composition and timing.

“And then there’s us, as a viewer, seeing all of these different layers of what’s going on. I think it’s just a great show that illustrates a record of our time,” she adds.

To illustrate the enormity of the billboards, Landau references a photo where a man paints the finishing details on a hamburger bun, pointing out that his head is about the same size as a sesame seed.

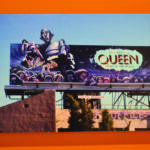

Many artists gave their designs a 3-D effect by extending the image outside of the billboard’s frame. Quite a few included no identifying text, instead relying on people recognizing the visuals that adorned the bands’ album covers.

“It’s kind of an insider thing. But even at the time, a lot of these were head scratchers, because you didn’t necessarily know who it was or what they were selling. And they didn’t really care,” says Landau.

“Another thing is, they knew that the viewer had about seven seconds to see it and figure out what it is. Of course they didn’t always figure it out. They were designed to be very bold and still clever; to get your attention and keep it.”

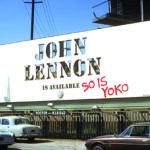

He says Jac Holzman, founder of Elektra Records, is credited with erecting the first rock billboard in 1967 to promote the Doors. Holzman called it a “very large calling card.”

Rhinoceros, another band Elektra attempted to establish, was not as successful, despite the creation of a dramatic, psychedelic rhinoceros billboard.

“It didn’t ever catch on or become a big success, but I think the billboard is spectacular,” says Landau.

The famed ‘Abbey Road’ billboard, based on the Beatles’ last studio album cover, had no text but its depiction was clear, even after Paul McCartney’s ‘decapitation.’

A conspiracy theory of the day claimed that Paul had died in a 1967 car accident and had been secretly replaced by a look-a-like. When a teenaged vandal sawed off (and kept) Paul’s head, Capital Records opted to leave it that way to play off the rumor.

A more enigmatic billboard, promoting the Who’s rock opera album ‘Tommy,’ contained just two shiny chrome ‘eyeballs.’

“People were driving by, and they just had to capture attention,” says Landau.

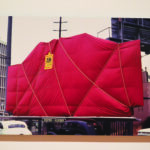

Another generated interest by being covered up.

“The artist Christo had just done a big thing in California, so this clever art director said, ‘Let’s cover up a billboard,’” Landau explains.

“It was a trick to create buzz. And three weeks later they said, ‘We’re going to have an unveiling.’ All the press shows up, and they take the thing off, and it was just something promoting Rick Wakeman. It was nothing special, but they got all this interest by doing that.”

A sequential campaign promoting Pink Floyd’s ‘The Wall’ began with a fake brick wall.

“And then slowly, over time, they peeled the bricks off to reveal the design. You had to pass it two or three times to get the full message,” he explains.

Some were graffitied, including a controversial image promoting the Rolling Stones’ ‘Black and Blue’ album, on which a women’s group wrote ‘This is a crime against women.’

Landau’s photo is in black and white, what his camera had at the time. By the time he came back with color film, the sign was gone. It was taken down after about two days, thanks to a successful protest.

Bruce Springsteen graffitied his own billboard, with a little help from his friends.

“He admitted it; he didn’t like the way his face looked,” says Landau.

Landau is working on a documentary about the remarkable artists who designed and created the billboards although, he says, “We’re rushing against the clock.”

The exhibit is on view through Sept. 1. For more information, visit VBMuseum.org.

Photos by Kerry Firth