Pelican Island Audubon Society came home from Florida Audubon’s annual assembly in Tampa at the end of October with the goods.

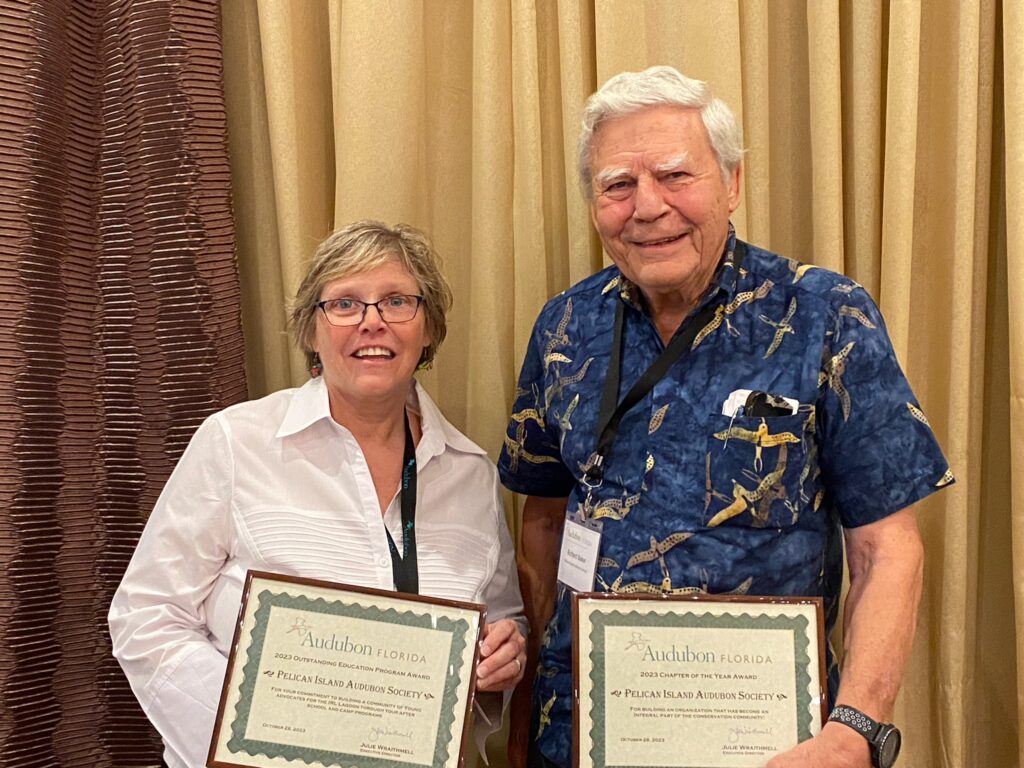

The group received two out of seven statewide awards given at the assembly – one for Chapter of the Year and one for Excellence in Education – fresh recognition of the 850-member local organization’s extraordinary efforts to hold the line against environmental deficit and degradation.

These are not feel-good, “participation” awards. The competition is intense and people with expertise in evaluating the importance and effectiveness of environmental efforts, including protecting birds and their habitats, make the picks.

The state organization has 45 independent chapters and approximately 100,000 members, according to Florida Audubon communications director Erika Zambell.

“The chapters are about equally divided between large chapters with over 500 members and small chapters with fewer than 500 members,” said Richard Baker, Ph.D., longtime president of Pelican Island Audubon. “Two Best Chapter awards are given each year – one for best large chapter and one for best small chapter.”

By those numbers, if the awards were evenly distributed in a pro-forma manner to give everyone some love, PIAS would be due a best chapter award once every 22 or 23 years. In fact, it has won the best large chapter award five times in the past 20 years.

“Pelican Island Audubon Society (PIAS) was selected as the Large Chapter of the Year [in 2023] based on the quality, diversity, and sustainability of their many programs . . . their commitment to education and engagement with non-traditional communities, and their focus on combating climate change through their ‘Trees For Life’ program,” according to a press release provided after the assembly.

PIAS received it’s 2023 Best Education Award for its “Audubon Advocate programs with four Title 1 elementary schools and its summer camp program,” the press release continues. “New in 2023, Pelican Island Audubon held its first seasonal nature camps for the Children’s Homeless Foundation of Indian River County. The program uses nature as a healing modality and an introduction to conservation and making a physical connection to the natural environment.”

“We are in our 9th year with the Audubon Advocate program and have graduated more than 800 fifth graders,” Baker told Vero Beach 32963. “Hiking, bird watching and bird identification, learning to use binoculars, photography, nature journaling, and self-portraits of themselves in nature are all part of the program.

“The campers went to the Sebastian inlet seining for fish and aquatic animals, guided by the park scientists. They held starfish for the first time and went on pontoon rides on the Indian River Lagoon to explore the unique estuary. The campers work with an art teacher who teaches sketching techniques and bird drawing,” as well as other scientists and teachers.

At one of the schools they support – Pelican Island Elementary School – PIAS purchased 18 parcels of scrub habitat with scrub jays, gopher tortoises and other animals around the school and provided more than 20 pairs of binoculars so children can observe wildlife near their classrooms.

“We also helped the teachers revamp the K-thru-5th grade curricula to support the School District’s designation of Pelican Island Elementary as an environmental science school,” Baker added.

PIAS also operated for years a school garden program at Pelican Island Elementary and other IRC schools, building raised beds and providing topsoil, plants and gardening tools, teaching students how to grow food and flowers in their own backyards.

This year’s awards in Tampa add to a long list of earlier awards collected by PIAS in recent years, including two earlier Best Education Awards and three Best Conservation Project Awards from the state organization, along with additional awards from the Indian River County School District, the Florida Education Foundation, the two-million-member national Audubon organization and the U.S. Department of the Interior.

“That one was a surprise,” Baker said of the federal award. “We got it in 1992 for the first coastal cleanup Pelican Island Audubon did in 1986 – which turned out to be the first coastal cleanup the U.S. Department of the Interior was aware of in the U.S.!”

Coastal cleanups have since become environmental mainstays across the U.S. and around the world.

Under the heading of “think globally, act locally,” PIAS functions as a conservation, restoration and nature education dynamo in and around Indian River County while also being part of Audubon’s statewide efforts and an important cog in the national organization that has led many of the most important efforts to protect the natural world and the quality of human life for the past 120 years.

From stopping the use of DDT, which was wiping out bird species at a rapid rate like a demented Mr. Clean wiping children’s drawings off nursery walls before it was banned in 1971, to preserving awesome tracts of irreplaceable wilderness to spearheading countless pieces of environmental legislation, the National Audubon Society has been an indispensable force for preservation of the natural world, which scientists say is essential to human wellbeing.

In the same timeframe, Florida Audubon has had its shoulder to the wheel in the Sunshine State, convincing Teddy Roosevelt to designate Pelican Island as the first national wildlife refuge, helping save Whooping Cranes and Bald Eagles from extinction, preserving Big Cypress Swamp and acting in the forefront of the effort that led President Bill Clinton to authorize the Everglades Forever protection and restoration act in 1994, committing $7.8 billion to save that unique wilderness ecosystem back when a billion dollars was a lot of money.

Locally, Pelican Island Audubon has a long list of impressive accomplishments. They include founding the Environmental Learning Center, playing a leading part in promoting and passing three county conservation land acquisition bond issues worth a total of $125 million, launching a program to plant 100,000 trees, and saving a large tract of wilderness along the lagoon that now is the Oslo Riverfront Conservation Area, where PIAS built its whimsical education headquarters with birdhouse-like structures, a traditional Old Florida breezeway, gardens, art rooms and museum-like displays.

The group also has organized and hosted annual conferences on Transforming Landscaping for the past five years with the goal of educating people about how they can help reduce climate change and pollution of the Indian River Lagoon by removing their grass and planting native plants. The well-attended conferences attract people from around the state and country. The 5th annual Transforming Landscaping conference will take place on Saturday Jan. 20, 2024.

Whether taking people on birding tours, kneeling in the dirt to plant a native tree or filing successful lawsuits to stop harmful polices or development, Pelican Island Audubon is Indian River Counties most active conservation organization.

“We have a great board and three super staff – Executive Director Donna Halleran, Office Manager Bob Montanaro and Environmental Educator Lauren Reeves – and chapter members that make our chapter dynamic in giving donations and volunteering their time,” Baker said. “The board works hard to submit grant applications, and thus though generous donations and grants we have greatly expanded our conservational, advocacy, and educational efforts.”

All true, no doubt, but its also true that the success of this under-sung, grassroots organization owes much to Baker himself, a charismatic leader who continues in his 80s to fight a determined rear-guard action against human caused environmental harm and the separation of people – especially children – from the beauty and healing influence of the natural world.

A longtime University of Florida professor and distinguished research scientist before his retirement, Baker received Audubon Florida’s statewide leadership award in 2018. In 2011, he was selected from tens of thousands of Audubon volunteers nationwide to receive the Charles H. Callison National Volunteer Award from the National Audubon Society for “working tirelessly as an advocate for conservation in his community.”

Baker, who has a direct, sometimes abrupt manner but is also quick with a smile, “is steadfast, resilient and epitomizes the standards we look for in volunteer leadership,” according to Eric Draper, who was executive director of Florida Audubon when Baker won the national award. “He really stood out in the whole country. This is the highest award for an Audubon leader.”