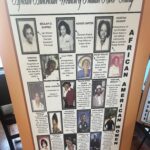

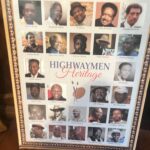

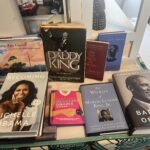

GIFFORD — Newspaper clippings, posters, school yearbook photos and paintings fill the space in what was once a vibrant church hall.

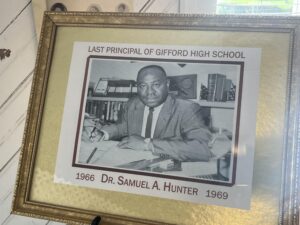

A yearbook photo inside the Gifford Historical Museum & Cultural Center shows Dr. Samuel A. Hunter, the last principal of Gifford High School PHOTO BY NICK SAMUEL

Here, a voice echoes the stories of countless Gifford pioneers who dedicated their passions to improve the community.

For Jonnie Mae Perry, keeping alive such stories of the generations who preached, tilled the soil, ran businesses or thrived in the small town is not only a privilege, but a “sense of duty.”

“History represents our past and future. If we don’t preserve history, we have no idea what was,” said Perry, executive director of the Gifford Historical Museum & Cultural Center, located off 45th Street and 28th Court.

“We owe it to ourselves to stay strong and connected. That’s the respect I give to my enslaved ancestors…fifth generation of the enslaved.”

Now, Perry is getting further recognition for her work at the small museum touting the legacy of Gifford’s predominantly Black community.

From left to right: Linda Barker, president of AAUW Vero Beach, Jonnie Mae Perry, executive director of the Gifford Historical Museum & Cultural Center with her husband Percy Perry, Vera Smith, Gifford Historical Museum & Cultural Center, and Lois Miles, AAUW Vero Beach. PHOTO BY JESSE ROMIMORA

Perry was honored Wednesday with the ‘Spirit of Community Award’ during the annual Florida Commission on the Status of Women luncheon held in Orlando.

The accolade recognized Perry’s achievement in obtaining a $493,000 grant last year from the Florida Department of State’s African-American Cultural and Historical Grant program to go toward the dream of expanding the museum.

That will mean more stories and testimonies to tell, more exhibits to show.

The award also honored Perry’s service with American Association of University Women, a national nonprofit established in 1881 to advance equality for women and girls through advocacy, education and research. Perry was the first Black president for the Vero Beach chapter for AAUW, serving three consecutive terms from 2019 to 2022.

A church becomes a museum

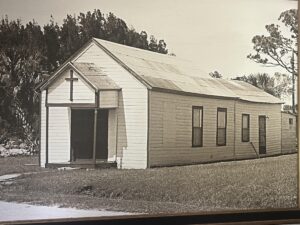

An old photo of the Historic Macedonia Church after it was built in 1908 in Sebastian. The church was later relocated to Gifford and restored into a museum. PHOTO BY NICK SAMUEL

Other stories of Gifford, both written and oral, paint a picture of a town that previously had several prosperous Black-owned businesses during the ’50s and ’60s. Some businesses from that era are still in operation, including John’s Barbershop, Guy Colley Grocery Store, Mosley Grocery Store and Smith Food Market, according to Perry.

“My father had Brown’s Standard Oil Gas Station on 45th Street. I grew up pumping people’s gas,” Perry said. “We have a responsibility to learn history and continually learn.”

But while private businesses dotted the community, it was the churches in Black communities that were crucial during the Civil Rights Movement of the ’50s and ’60s, Perry points out.

The churches became a safe haven for African-Americans, many of whom participated in non-violent protests in efforts to push lawmakers to end legalized racial segregation and discrimination in America.

“Lots of pastors and church members were part of the Civil Rights Movement and had meetings there,” Perry said. “Pastors educated from the pulpit and inspired people to get involved in the movement for the better of all of us.”

The Gifford Historical Museum & Cultural Center is a piece of history itself, previously operating as the Historic Macedonia Church. The 1,150 square-foot wood-framed building now sits at the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Park and Trail, across the street from Gifford Middle School.

The Gifford Historical Museum & Cultural Center. PHOTO BY NICK SAMUEL

The building where members prayed and sang on Sundays was originally built by Black railroad laborers – working on Henry Flagler’s famed railway line along Florida’s east coast – in Sebastian in 1908.

The church was relocated to Gifford in 1994 to serve as a Black historical museum for the county, according to the Indian River County Historical Society. Gone were the songs of praise and the stories of survival and travail.

Or so it seemed.

“The church sat idle for 20 years,” Perry said.

Under the direction of the Progressive Civic League of Gifford, the church underwent a restoration and officially reopened as a museum on Feb. 24, 2018.

Gifford Pioneers

A peek inside the Gifford Historical Museum & Cultural Center shows photos of leaders who strived to improve education, living conditions and activities for the youth in the community.

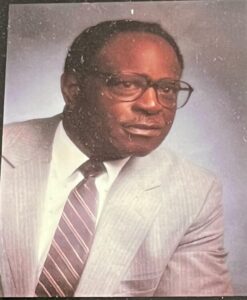

Dr. A Ronald Hudson, first Black principal of Vero Beach High School and co-founder of GYAC. PHOTO BY NICK SAMUEL

These men and women remain well-known throughout Indian River County, with some still heavily involved in civics.

Some of these pioneers include former local NAACP chapter President Victor Hart Sr., who served for 45 years and was a member and catalyst for the Progressive Civic League of Gifford. Also featured is Dr. A. Ronald Hudson – the first Black principal of Vero Beach High School and co-founder of Gifford Youth Achievement Center that currently serves 243 students in its afterschool program. There are also pieces on Freddie Woolfork, community advocate, former president of the Progressive Civic League of Gifford and the longtime public relations director for GYAC.

Another notable name that stands throughout history in Gifford is Joe Idlette Jr., who sued the School District of Indian River County in 1964 to successfully end segregation in public schools, said his son Joe Idlette III, another longtime president of the town’s civic league. The elder Idlette became a school board member for the school district in 1974, a role he served for 20 years.

There is also longtime community leader Tony Brown, the local NAACP president who was elected in 2008. Another well-known community staple is Gifford Youth Orchestra Founder Rev. Dr. Crystal Bujol, who has taught children in the town how to play music – strings, percussion, piano, and later adding drama, voice and dance – for 20 years.

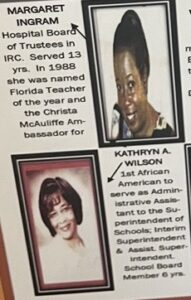

Top right: Margaret Ingram, Founder of the Science Institute of Discovery held at GYAC, retired educator who taught at SDIRC for 35 years, Florida Teacher of the Year 1988, Christa McAuliffe Ambassador for Education, served 13 years with Hospital Board of Trustees in IRC. Bottom left: Kathryn Wilson, first Black person to serve as administrative assistant to the superintendent in IRC, interim superintendent and assistant superintendent, first black woman elementary school principal in IRC, first black woman school board member, served six years. PHOTO BY NICK SAMUEL

One pioneer, J. Ralph Lundy, led the movement for Gifford – located north of Vero Beach – to have clean water, paved roads and street lights. Ralph Lundy, who was 90 years old when he died in April 2009, served as president of the Progressive Civic League of Gifford in the early ’60s.

“The water was yellow and not drinkable,” said Jay Lundy, son of J. Ralph Lundy. “We had to get our drinking water from downtown.”

Lundy said he moved with his family from Miami to Gifford – largely a settlement for Black families since the 1880s – when he was a young boy. Lundy remembers a vastly different Gifford when he was growing up.

“When you look at Gifford now, you don’t get a true picture of the development as a community. We had thriving grocery stores, gas stations and several other businesses that were pillars and landmarks for us,” said Lundy, director of the Youth Employability Program at GYAC.

The origin of Gifford begins with a man named William Brown, who historians say was the first Black settler in the area. Brown – who was born in 1837 on a cotton plantation near Savannah, Georgia – was granted a U.S. Homestead for 60 acres along the Indian River, according to the Indian River County Main Library Archive Center.

Over the years, Brown became a successful farmer, clearing and cultivating his land. The area expanded into a settlement called Brownsville in honor of Brown, historians say.

“The Browns were popular and highly regarded by their neighbors who often came to them for advice,” archive documents show. The name of the settlement was renamed to Gifford – after another early pioneer and railroad stationmaster Charles Gifford – when officials discovered there was another town called Brownsville already existing in North Florida.

Another early pioneer William Edward Geoffrey – who worked on the Florida East Coast Railroad – bought 80 acres of land in 1901 in Gifford, archives show. He donated the land for a school to be built for Black children who were not allowed to attend the white schools.

The campus – considered by locals as the heart of the community – was known as Gifford High School until integration, with the last class graduating in 1969. The school then transitioned into a middle school.

Anna Lee Lane – a centenarian – is the oldest living graduate of Gifford High School, Perry said.

Gifford – which now has a population of more than 5,000 residents, according to the 2020 census – was known as the railroad and citrus grove community. But with progress came change.

“In most historical Black communities (today), you see a decline of black businesses,” Lundy said. “It’s a reflection of what has occurred overtime.”

Lundy said his father, who was known as “Gifford’s spokesman,” had worked for the Indian River Press Journal. The elder Lundy even had a weekly column called “Gifford News.”

Ralph Lundy established the “Our Father’s Table Soup Kitchen,” which fed struggling families. He also started several little league baseball teams in Gifford and was heavily involved with the Indian River County Float Committee, Lundy said.

Lundy said the leadership from Gifford pioneers are etched in history and will hopefully be passed down to future leaders.

“These leaders led out of their hearts and time,” Lundy said. “Today we do things as part of our job. It’s an extension of what we do.”

The Future

Today, Perry says there are more stories to tell about the lives of those who made up Gifford.

Jonnie Mae Perry, left, and her husband Percy Perry hold up her award during the annual “Spirit of Community Award” luncheon held June 28, 2023, in Orlando. PHOTO PROVIDED BY JONNIE PERRY

The grant allowed Perry to secure contracts with Rhodes & Brito Architects, based in Orlando, and Lordes Cultural Resources, an international consulting firm.

To her husband, the grant and the award are recognition for the hard work his wife has poured into preserving the town’s unique history.

“I was excited she won this prestigious award,” Perry’s husband Percy Perry said. “She deserves it.”

Perry didn’t always plan on becoming a historian. Her interest in genealogy peaked in the ’90s when the Gifford native began retracing her own family’s history back to slavery.

Later, a friend reached out to her for a favor.

“I was asked by Mr. Godfrey Gipson to create a museum and Black history library in the historic church. He said that’s what the vision was for the community,” Perry said. “Well, I was asked so it became a labor of love and passion. So, God had a plan for my life and I just continued to be guided and grow.”

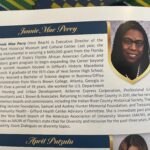

Perry, a Gifford pioneer herself, is heavily involved in the community. She is the immediate past president of the Vero Beach branch of the American Association of University Women and has served as AAUW of Florida’s state chair for diversity and inclusion the past three years, her biography shows.

Perry, a 1973 Vero Beach High School graduate and 1977 alumna from Morris Brown College in Atlanta, has worked for the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Professional Creative Consultants and J. Brown & Associates. She has also served on several local boards and commissions including the Indian River County Historical Society, The Laura Riding Jackson Foundation, Samuel and Audrey Hunter Memorial Foundation and the Treasure Coast Community Health – Gifford Health Center Advisory Committee.

Now, Perry is laser-focused on transforming the center into a community staple.

An undated photo shows members of the Progressive Civic League restoring the Historic Macedonia Church after it was relocated from Sebastian to Gifford. PHOTO BY NICK SAMUEL

Perry said she plans to expand the museum into a 15,000 square-foot building. The center will be extended at the back of the property and include a new exhibit hall, a library, traveling cafe, banquet hall and an arts studio.

Perry said she will arrange a visionary workshop with community stakeholders later this year.

“This will be a legacy not just for the people of Gifford, but the entire county,” Perry said.

No architectural plans have yet been drawn up for the extension, which is still in the development stage. Perry said she hopes her recognition will inspire and motivate young girls in Gifford to get involved in the community.

“Young people should know about the history of Gifford. It will give them a sense of pride. Gifford was once a thriving Black community. It has a rich history,” Perry said. “If we don’t preserve history and tell the stories, it will be lost and unknown. That will be a tragedy.”

Photos by Nick Samuel

- Gifford Historical Museum & Cultural Center

- Gifford Historical Museum & Cultural Center

- Gifford Historical Museum & Cultural Center

- Gifford Historical Museum & Cultural Center

- Gifford Historical Museum & Cultural Center

- Gifford Historical Museum & Cultural Center

- Gifford Historical Museum & Cultural Center

- Gifford Historical Museum & Cultural Center

- Gifford Historical Museum & Cultural Center

- Gifford Historical Museum & Cultural Center

- Gifford Historical Museum & Cultural Center

- Gifford Historical Museum & Cultural Center

- Gifford Historical Museum & Cultural Center

- Gifford Historical Museum & Cultural Center