The Johnson-Sea-Link Program at Harbor Branch had it all – romance and tragedy, camaraderie and practical jokes, adventure on the high seas and extraordinary discoveries.

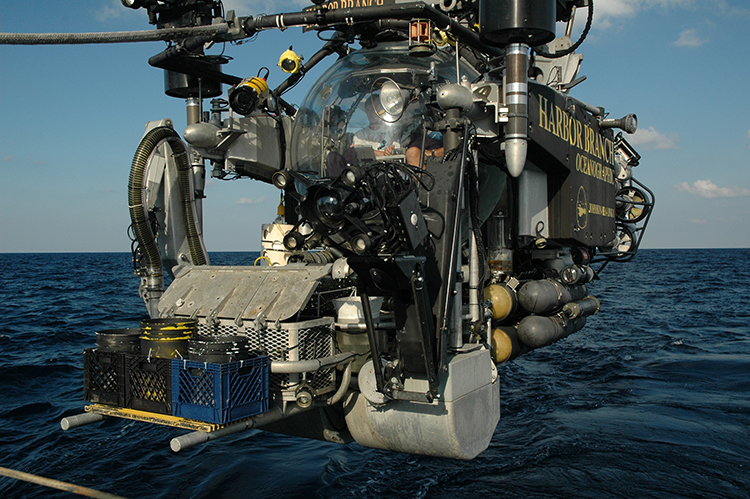

The Johnson-Sea-Link sub- mersibles – JSLs for short – look like illustrations for a Jules Verne novel. Now retired, the 20-foot long, 4-person craft could go down 3,000 feet into the ocean, to places utterly unknown across the whole expanse of human history until the 1970s when they began to carry eager, young researchers into the deep.

At a lecture last month that was part of Harbor Branch’s 50th anniversary celebration, four of those researchers, a little older now, recalled the scientific excitement and personal wonder they felt exploring new worlds during the four-decade Sea Link program, which was headquartered here on the shore of the Indian River Lagoon just south of the county line.

“Between 1971 and 2010 we made over 9,400 dives around the world,” said John Reed, a research professor and coral expert who came to Harbor Branch in 1976, straight from graduate school, just in time to help discover the Oculina Reef, a vast marine treasure unique to the east coast of Florida that is home to more than 300 species of marine life.

Paired with three research ships that could carry them to distant parts of the globe, put them in the water and retrieve them after dives, the JSLs were used for ground-breaking research from the Galapagos to the Great Lakes, from the Gulf of Mexico to the Mediterranean, from the Bahamas to West Africa.

On those far-flung dives, scientists came nose-to-nose with a Greenland Shark – a creature that grows to 20 feet in length, can weigh more than a ton, lives to be 500 years old and can dive to 7,000 feet.

They also saw an 8-foot-high sunfish in a part of the ocean where it wasn’t supposed to be, and discovered “hundreds of previously unknown or undescribed species,” according to a Johnson-Sea-Link exhibit at the Elliot Museum in Stuart.

“What was most amazing is that we got to dive and see species that no one else on earth had seen,” Reed wrote in an email to Vero Beach 32963 after the lecture. “There have been hundreds of publications resulting from dives by scientists using the Johnson-Sea-Link submersibles for biomedical research, fisheries research, and discovery of new reefs that are now protected as marine reserves.”

In just the final 10 years of the program, between 2000 and 2010, Harbor Branch’s ships and submersibles were used by 3,560 scientists from 79 universities and 15 government agencies, according to Reed, with dramatic Sea Link dives featured in documentaries filmed by Discovery Channel, National Geographic, BBC, IMAX, History Channel, the Science Channel and others.

“We were on the national and international news frequently,” Reed told the audience at the lecture. “Harbor Branch was known worldwide because of our submersibles.”

Besides helping discover the Oculina Reef, Reed is known for his discovery and exploration of hundreds of other reefs in or near Florida waters.

“In 2001, we got a grant to do biomedical research and we documented 300 deep-water reefs off the straits of Florida that ranged from 50 to 500 feet tall,” said Reed, who was instrumental in getting a 23,000-square-mile area around the reefs protected from bottom fishing that would destroy the delicate, ecologically productive structures. He also helped gain federal protection for much of the Oculina Reef.

But it all started with Edwin Link, an Elon Musk-type character who held 27 U.S. patents at the time of his death in 1981.

Link invented the flight trainer – cobbling together parts from his family’s organ factory – that was used to train half a million allied airman in the Second World War, a major contribution to victory in Europe and the Pacific.

After the war, his interests turned to marine archeology and he equipped a research ship and fabricated the Deep Diver, a Sea Link precursor that enabled divers to work at greater depths for longer periods of time than they could before.

In 1971, he teamed up with fellow visionary Seward Johnson, part of the Johnson & Johnson family, who shared Link’s fascination with the deep ocean, to found Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute on the largest privately-owned deep-water channel in Florida.

That same year, backed by Johnson’s fortune, Link and his team of engineers designed, fabricated and assembled the first Johnson-Sea-Link in a machine shop 8 miles south of Sexton Plaza.

Two years later, the greatest mishap in the program’s history occurred when Link’s son, Clayton Link, and another crew member were killed during the JSL’s 130th descent. Diving near Key West, the submersible became entangled in the cables of sunken Navy destroyer and the two men died of carbon dioxide poisoning before they could be rescued.

Despite the tragedy, Link and Johnson persevered, continuing to explore the deep ocean and commissioning a second submersible, the Johnson-Sea-Link 2, in 1975.

By the mid-1980s, research had expanded to include a hunt for biomedical compounds that could be used to fight infections and cancer.

Research professor Shirley Pomponi came to Harbor Branch at that time.

“I was recruited for the new drug discovery program because of my expertise in sponge biology,” Pomponi said. “It was December, and I was living in Pennsylvania. It had already snowed three times and when they invited me to go on a research expedition to Bahamas, I said, ‘Send me a ticket and I’m there!’”

Sponges are rich sources of potent compounds because they are stationary creatures and have to use chemical “weapons” to defend themselves from other marine creatures. Those same compounds can in some cases kill cancer cells and antibiotic resistant bacteria.

Pomponi, who vividly remembers her first JSL dive on Dec. 4, 1984, went on to make more than 300 dives as a Harbor Branch scientist. She said she loved the camaraderie among the scientists and crew, recalling how everyone would turn out on deck when a sub came up to see what had been found and help sort the specimens.

“We were away from our families for weeks and months, out at sea, and we developed close personal and professional relationships with our colleagues, wonderful friendships,” Pomponi said. “There could be 10 people on the ship or as many as 40. We hit the deck at 6 a.m. and weren’t done until midnight sometimes, so we got to know each other pretty well!”

Camaraderie crossed over into romance at some point, when Pomponi and chief sub pilot, Don Liberatore, fell in love and got married.

“It was a gift,” Pomponi said of her years as a Sea Link researcher. “I consider myself incredibly lucky to have met and married Don and to have had the chance to do research in the JSLs.

“There is a line in a Jimmy Buffet song about the ocean – ‘in your belly you hold the treasures few have ever seen’ – and I am one of those few. I got to see and do things I never ever thought I would get to see or do. It was a thrill.”

The ongoing Harbor Branch drug discovery program has so far catalogued and stored for research more than 30,000 marine specimens with possible medical potential and isolated 400 unique chemical compounds, several of which have been made into experimental drugs.

Amy Wright, an organic chemist and Harbor Branch research professor who founded the drug discovery program, played a video when it was her time to talk that captured the sense of giddy excitement that went hand in hand with careful scientific observation.

“We are in a fabulous place, just so fabulous,” she says in the video, shot below 2,900 feet in the Bahamas. “Look at that humongous sponge over there!”

She and her sub mates were working along the edge of an undersea drop-off within a few feet of their depth limit when she saw a shelf further down teeming with the kind of fantastical life forms they were seeking.

Longing can be heard in her voice when she says, “Oh, there is a ledge down below us that is so enticing – but just out of reach!”

Research Scientist Dennis Hanisak, the fourth speaker and the host of Harbor Branch’s “Ocean Science for a Better World” lecture series, conveyed a sense of the drive for discovery that characterized the program.

When he heard in the 1980s about a little-known type of algae surfacing in the Gulf of Mexico, he did some quick library research and then flew to Texas where one of the dive ships was anchored, waiting for better weather to cross the Gulf back to Florida.

When the ship arrived after dark at the place he wanted to dive, he was told – after enduring several days seasick and confined to his bunk in continuing rough weather – that it would be too dangerous to descend under current conditions.

At the last minute, the weather shifted slightly, and the operations director turned to him and said, “Are you sure what you think is down there actually is here?”

“I said, yes – what else was I going to say,” Hanisak told the lecture audience. “The OD said, ‘OK, let’s give it a try. We may have to bring you up early.’

“Before I knew what was happening, we did a quick pre-dive check and I was whisked into the sphere of the Johnson Sea Link, heading down into the water.”

It was his first dive. Don Liberatore was his pilot.

At 202 feet they found the hoped-for algae bed he calls ‘my field of green.’

“We were the first to see that habitat,” he said. “That night was an incredible personal and professional experience that opened my eyes to the possibilities of JSL dives.”

There were a lot of incredible nights and days during the 39 years the program lasted, but Harbor Branch ran into financial difficulties after the death of Seward Johnson and was acquired by Florida Atlantic University in 2007.

The university did not continue to fund the JSL program at the level needed and in 2010 the research ships were sold, and the submersibles mothballed.

An article published in Nature that year called it “the end of era,” and the scientists who had used the submersibles weren’t happy.

“It’s definitely a loss to the world’s deep-sea research community, and to future generations of scientists,” Chuck Fisher, a marine biologist at Pennsylvania State University who made close to 100 dives in the subs, told Nature.

Ocean exploration and research didn’t stop, though. FAU Harbor Branch scientists immediately switched to ROVs – remotely operated vehicles – to probe the deep ocean and keep gathering knowledge, an enterprise that continues today.

“We actually have an operation coming up next month funded by NOAA, May 2 through May 14, on the Flower Garden Banks,” said Wright.

Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary is a 160-square-mile area in the Gulf of Mexico that contains 17 different living reefs. NOAA will post ROV video of the underwater world on its website during the mission for anyone who wants to see the reefs and their inhabitants up-close and personal.

The 2022 Ocean Science Lecture Series concludes on April 20 with “Celebrating 50 Years of Ocean Science for a Better World,” a panel discussion with five of Harbor Branch’s top scientists.

Photos provided