Artmaking is in our genes, even in the United States, the country whose no-nonsense, self-sufficient mindset has reigned for as long as our country has been a country. Far from being an impediment, our pioneer attitude encouraged our uniquely American, self-taught art forms made by, and for, regular folks. An exhibition on display at the Vero Beach Museum of Art through Jan. 2, 2022, pays homage to this artform.

American Perspectives: Stories from the American Folk Art Museum Collection is a traveling exhibition that originated at that New York City museum. It is touring into 2023 through the auspices of Art Bridges, a foundation that partners with museums to bring shows to a wider public.

American Perspectives was originally assembled by independent curator Stacy C. Hollander from the Folk Art Museum’s collection and mounted in its galleries from February 2020 to January 2021. The exhibition was curated for travel by the museum’s curator Emelie Gevalt, who presented the VBMA’s members’ opening lecture earlier this month via Zoom.

Gevalt noted that the 80 artworks in the show are organized into four sections: Founders, Travelers, Seekers and Philosophers. The exhibition includes objects that speak to American ideals of nationhood, freedom, community, imagination, opportunity and legacy.

The artists represented lived from the early days of the republic to our own times. They are male and female; young, middle-aged, and elderly; Black and white, enslaved and free; immigrant and Indigenous. In short, the exhibition strives to include all variety of persons who helped to build, and comment upon the building, of the country as we know it today.

Gevalt led a virtual tour of the exhibition’s highlights, as well as those she deemed her personal favorites.

The first object she spoke on was a 1794 needlework picture embroidered in silk thread on a 17- by 20-inch piece of silk fabric, which features a mother with her children in a fanciful landscape. The maker of the picture was 12-year-old Sally Hathaway, whose family lived in New York City and Massachusetts, and were well-to-do, or aspired in that direction.

The people in it are dressed to the nines in late-18th century fashion. Mother wears a turban with a spray of feathers erupting from its top; the little girl at her knee sports a green top hat with an artificial flower, her orange shoes matching her elegant, full-length gown. A boy, accompanied by his dogs, is shown carrying a little bird to the group. He wears a blue coat and ruffled shirt, and his stockings are of silk. Sally competed her picture with a trompe l’oeil curtain that frames the top and sides of the scene, as though it were a stage set on which the curtain has just risen.

Gevalt noted the importance of such a needlework creation to a girl’s prospects for her role in society as a woman of culture and grace, who nevertheless knows her way around the practical matter of a needle and thread. Sally’s subject matter presages the life that her mother no doubt envisioned for her – that of a mother and wife whose husband is off somewhere, amassing the family’s wealth.

A painted wood blanket chest is the oldest object on display. Emblazoned with the name of its owner, a Schoharie Valley, N.Y., farmer named Jacob Kniskern, the chest may have been made for him by his brother, Johannes. The date on the chest, 1778, was an eventful year for Jacob. A Continental Army soldier, he was taken prisoner by British forces and held in Canada. After escaping, Jacob returned home to find his farm and community burned to the ground. The chest survived the war, and so did Jacob, who rebuilt his farm when the war was won. By the end of his life, he was wealthy enough to own six additional chests, which would have held valuable belongings and textiles.

The story of early America was not all wealth realized and reinvention accomplished. A jug by master potter David Drake bears testimony to this. The utilitarian object, created in 1853 in Edgefield County, S.C., bears the cursive inscription “Dave.” As an enslaved man, Drake’s habit of signing his work was exceedingly rare for the time, said Gevalt. In antebellum America, it was against the law in many southern localities to teach enslaved people to read and write. Yet Drake managed not only to sign and date his work, he sometimes also inscribed Bible verses or rhyming couplets on his vessels.

In 2016, a VBMA exhibition, “David Drake, Potter and Poet,” appeared in the Schumann Gallery and was reviewed by Vero Beach 32963. That exhibition was organized by the VBMA, which promoted it as the “first major museum of pottery by the enslaved African potter known as ‘Dave’” since a 1998 survey exhibition curated by Jay Williams for the University of South Carolina’s McKissick Museum. Thirty-one of Drake’s large vessels and storage jars, complete with inscribed verses, were on display in that memorable exhibition.

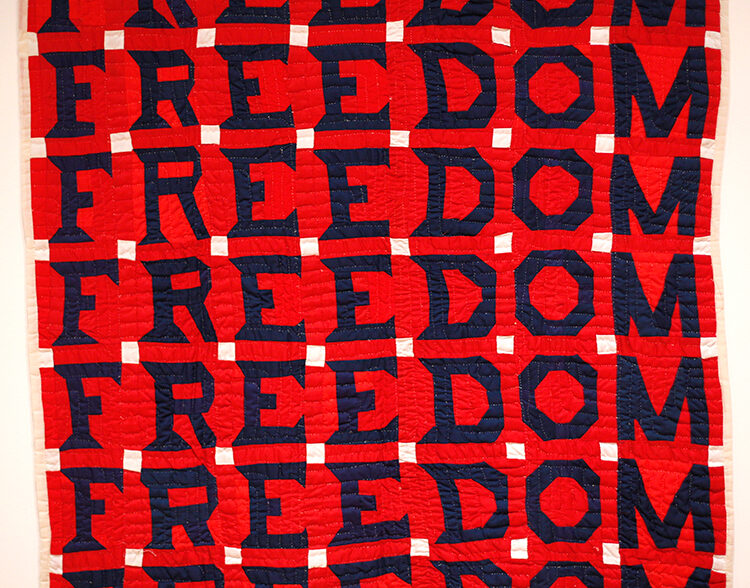

A more recent Freedom Quilt, stitched in 1983 by Jessie B. Telfair of Parrott, Ga., honors the civil rights movement of the mid-20th century. The 74- by 86-inch artwork shouts the word “FREEDOM” seven times, spelled out in letters of dark blue fabric against the quilt’s fiery background of red; the whole punctuated with white accent squares. Among the exhibit’s marvels, Telfair’s quilt is notable for its dazzling combination of craft, graphic design and message. This object will simply not allow you to ignore it.

As well it should not. In the 1960s, Telfair was fired from her job as a cafeteria worker when her white employers found out that she, as a Black woman, had registered to vote, and was part of an organized effort to register other African Americans to do the same.

Born in 1958 in New York City to Puerto Rican parents, Nick Quijano Torres, like “Grandma Moses” (aka Ann Mary Robertson, also represented in this exhibition), is a memory painter, who recalls in his work the imagery and people of his childhood. Instead of Moses’ New England country snow scenes, where sleighbells jingle and boys fight snowball battles, Quijano Torres’ visual memories are densely packed portrayals of the people that that populated his neighborhoods – first in New York and, after the age of 13, in Puerto Rico, where he completed his degrees in architecture and environmental design.

In this show, his “Memories of the Veteran” is a tiny, 6.25-inch-square painting that depicts a woman with two children, a boy and girl, dressed in their best clothes. Seated indoors on a sofa, Mother wears a green dress and sips a cup of tea. Like the woman in Sally Hathaway’s needlework picture, Quijano Torres’ figure is an idealized woman of leisure. Her boy, standing at her right, and daughter, seated at her left, wear summery white outfits with white shoes and socks. Unlike the absent father in Hathaway’s scene, “Memories of the Veteran” includes a head and shoulders portrait of the missing father in uniform, hanging on the wall directly above his wife’s head. He, no doubt, is the founder of the comfortably furnished, middle-class parlor in which his family sits.

Memories of childhood will also be recalled by an elaborately carved and painted carousel horse by Marcus Illions, dubbed “the Michelangelo of carousel carvers” by the New York Times. Born about 1870 in the Russian Empire or in England, Illions began his career building circus wagons. By his teens he was documented as being in England, where he embarked on his specialty of carousel horses. He immigrated to the U.S. in 1888, where he carved horses and other animals for a Coney Island carousel manufacturer. Illions opened his own carousel company in 1909.

The horse in the current exhibition is fit for a prince or princess. The galloping white steed with gilded mane and green, blue and gold caparison is just the thing to ride merrily upon into the holidays.

Your seasonal guests will love this show, and so will you, no matter how often you visit.

Photos by Kaila Jones