Until scientists better understand the virus that causes the COVID-19 disease and figure out how to treat it and prevent it, the world is somewhat at the mercy of the novel coronavirus. So, it’s fortunate an army of skilled researchers are working to gain that knowledge – including one scientist with deep roots in Vero Beach.

Tucked away in a secure laboratory on the campus of Michigan State University, 32-year-old Daniel Vocelle conducts experiments with the live virus that has infected more than 3.5 million worldwide and killed a quarter million people.

Managing the university’s Flow Cytometry Core lab was not exactly the career Vocelle pictured for himself back in 2006 when he graduated from Sebastian River High School’s International Baccalaureate program and headed off to Vanderbilt University to earn a degree in chemical engineering. That is because the type of research Vocelle does today was not mainstream when he applied to colleges.

“They did not really offer degrees in the field of biomolecular engineering, so I had to wait and go back to graduate school,” Vocelle said. In the meantime, he worked in the Middle East in the oil industry.

When he returned to the states, he earned two doctorate-level degrees, one in chemical engineering and another in quantum biology, and took over managing the Michigan lab in February, just in time for his current research topic to emerge – the mysterious, novel coronavirus from Wuhan, China.

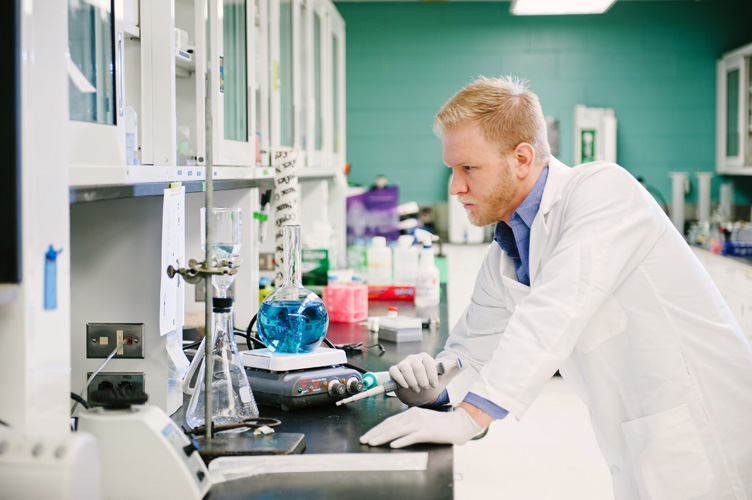

Vocelle works mostly alone or with one or two assistants in the lab on a deserted campus in East Lansing, Mich., where students were sent home in March for the spring semester. It’s a highly controlled atmosphere where no outside electronics are allowed. Conditions are kept at optimum levels to protect sensitive equipment, and Vocelle must dress in Biosafety Level 3 protective gear to work with the live virus. That means a full body, air-supplied, positive-pressure suit and a thorough decontamination shower before he can leave the lab.

But Vocelle said he feels safe – even when he goes home to his wife Amber and 14-month-old son Magnus – knowing how the lab is designed. It also helps that Amber is in her last year of medical school training to be a surgeon, so she is more keenly attuned to the science of his job.

“It’s not the suit that protects me as much as all the other safety precautions in place,” he said.

The university owns sophisticated flow cytometry equipment that can analyze 20,000 cells per second. That type of machine is more than the average researcher, hospital or company could afford to purchase, so Vocelle said the university writes grants to equip a top-notch lab and then trains scientists like him to operate the equipment and run the experiments for clients who contract to use it.

If some groundbreaking discovery is made, the university gets partial credit upon publication.

Three different research teams are designing experiments related to the virus that causes the COVID-19 disease. Two of those contracts are confidential, so Vocelle could only describe one of the three research angles.

By using the laser-assisted Flow Cytometers in the MSU lab, scientists are able to attach fluorescent molecules, which appear as microscopic glowing particles, to proteins in the deadly virus or to models of the virus to observe and track the markers and analyze the various ways the virus enters human cells and what it does once inside the cell. There’s a lot more to it, of course, but that’s a layman’s explanation.

Though the technology is complex, the experimentation process goes back to the same scientific methods learned in grade school. “They come to us with a question and we have Zoom meetings and go through the steps of designing experiments to answer that question,” Vocelle said.

That means Vocelle and two other scientists collect the needed materials and prepare samples in the lab, wait for the samples to be ready, run the experiments on the Flow Cytometer and then analyze the data with the research team. Occasionally outside researchers, professors and graduate students will come into the lab for simpler tasks, but Vocelle personally handles experiments on the lab’s most sensitive equipment.

Prior to being tasked with studying the coronavirus, the lab was conducting experiments related to agriculture and America’s food supply, veterinary medicine and cancer research. All told about 650 different researchers use the lab’s skilled personnel, equipment and resources.

The director of Ph.D. Career Development in the MSU Graduate School, Dr. Julie Rojewski, worked with Vocelle during his graduate study and research and in the university’s Broadening Experiences in Scientific Training program.

“He was an impressive student: curious, dedicated, hard-working. I’ve always thought of him as someone destined for great things because he is smart, reliable, funny and responsible. All around, a great person and a great colleague.”

Looking back on how he ended up in Michigan tracking minuscule glowing particles with multimillion-dollar microscopes, Vocelle credits not only his parents Louis B. “Buck” and Donna Vocelle, but also his hometown for launching him to success.

“I give the credit to the community of Vero Beach and my parents and their friends who, if I had an interest in doing something like working in a lab, they found a way for me to have an opportunity to work in a lab and get that kind of experience,” Vocelle said.

Dr. Peggy Jones of Vero Beach was Vocelle’s principal for four years at Sebastian River High School and she remembers him as a standout student in the prestigious and rigorous International Baccalaureate program.

“He was absolutely passionate and determined. He was one of those kids who you just knew he was going somewhere. On top of that, he is kind,” she said.

Vocelle said the education he received at Sebastian River High School was a great launching pad for the rest of his life. “The IB program was fundamental in developing me as an individual and getting me into Vanderbilt,” Vocelle said, adding that some of his favorite teachers and courses had nothing to do with science, but that they honed his ability to think critically and tackle complex material – skills he uses every day as a researcher.

Jones said she kept up with Vocelle for a few years but had lost track of him, and was extremely happy to hear he’s found such meaningful and important work.

“I am not surprised to hear what he is doing. If anyone can figure it out, Daniel will,” Jones said.