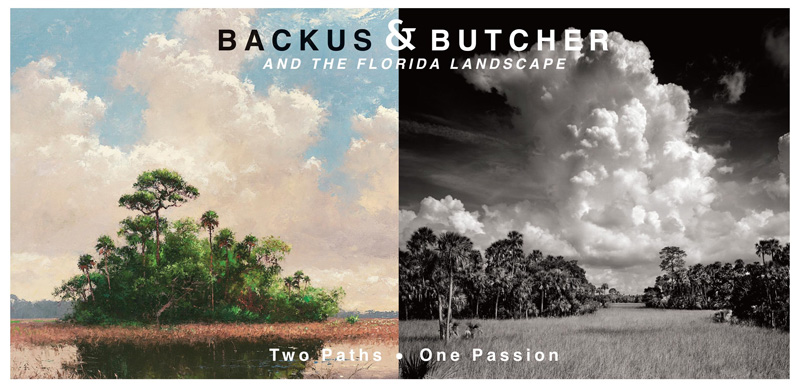

The works of two iconic Florida landscape artists, painter A.E. Backus and photographer Clyde Butcher, hanging side by side at the A.E. Backus Museum in Fort Pierce, are a fascinating study in contrasts: the jubilant hues of Backus’ billowing clouds and cypress trees compared with the starkly ominous swamps and storms of Butcher’s black-and-white photos.

While both artists convey the emotional power of nature’s beauty, they also call to mind the brevity of life. Fort Pierce still grieves for its loving and eccentric native son, Backus, nearly 30 years since his death. And fans of Butcher worry about his well-being, 22 months after the 78-year-old bearded bulwark of a man suffered a serious stroke at his home in Venice, on Florida’s southeast coast.

On March 30, Butcher will appear at a book signing at the Fort Pierce waterfront museum, where 13 of his large-format photographs are on view along with some of Backus’ best works, many on loan for the show.

Backus and Butcher and the Florida Landscape: Two Paths, One Passion is the third major show in the second season of J. Marshall Adams’ tenure as executive director of the museum. He joined the staff of the newly expanded museum after the retirement of longtime director Kathleen Fredrick. In his first year, Adams, the former director of education at the Vero Beach Museum of Art, carried out a show schedule set by his predecessor. This year, the exhibitions are all his doing; the Butcher and Backus show follows an exhibition of Highwaymen paintings, and before that, selected works of glass artists Dale Chihuly and Marlene Rose.

In inviting Butcher to show his works, Adams pointed out that there were “amazing similarities” between Backus and Butcher. “Both are in the Florida Artists Hall of Fame. Both have landscapes as their primary subject. They both felt nature was a refuge for them.”

For Butcher, nature is more than a refuge: It is healing him. After the May 2017 stroke and two months of rehabilitation, it was only a matter of months before he was shooting in the swamps again. The making of his first photo since the stroke, Myakka Lake 1, involved what he now calls his favorite photo prop: a four-wheeled walker with a built-in seat. He describes waiting patiently for the instant when luminous clouds seemed to launch out of a black sky toward the reedy shore where his walker was perched. Butcher snapped the shutter of his digital camera, his standard large-format camera traded for something lighter weight for his now-trying treks into the wilderness.

The notoriously intrepid Butcher was not new to a sense of mortality; he had had that lesson delivered in the harshest of ways, when his teenage son Ted was killed by a drunk driver in 1986. Butcher mourned the loss by heading into the swamp before dawn every day, driving “until there were no roads left to drive,” as authors Tom Shroder and John Barry, described in their book, “Seeing the Light.”

Butcher would hoist his heavy camera and equipment to his massive shoulders and begin a trek into primeval swamplands. He would return after nightfall, exhausted. Months later, he loaded up the resulting black-and-white images and hit the road, selling them at art shows across the country to whispers of “the next Ansel Adams.”

It was high praise for a man who started out studying architecture at California Polytechnic University. As Shroder and Barry tell it, after graduation and newly married to Niki, Butcher and a friend started a business building architectural models out of balsa wood in a rented farmhouse next door to a wild scene led by Timothy Leary.

Butcher had learned to make the models in college, learning how to photograph them in settings that made them look full size and developing the photos himself. When business tanked in the collapse of the real estate market, Butcher took up nature photography, selling his photos at art shows and eventually as decorator art at major department stores.

After a spell living on a sailboat, he and his wife and two children moved to Florida. After a string of challenges, they eventually bought a rare property within Big Cypress Preserve; the home of an old orchid grower and the 14 acres surrounding it. Today Butcher keeps one of his three galleries there with a darkroom in a warehouse in Venice.

Along the way, Butcher became an avid environmentalist, championing most fervently the Everglades.

“It was clearly a calling for him to settle here in Florida, to be in tune with his natural environment and to capture that in order to share it with others and to impress upon them that this is important,” says Adams.

While Butcher has had a prior exhibit at the Backus Museum, the notion of having a joint show was novel, Adams says. “Backus is considered the dean of Florida landscape painters. So when I got the idea of putting these two together, it was like, wow, wouldn’t that be cool. I was interested in seeing what the possibilities could be.”

Adams said he approached Butcher’s agent gingerly at first. “I was trying to be delicate. You don’t see his work in a lot of group shows; he’s kind of his own master. I didn’t want him to feel like I was not paying his work the proper respect.

“So I asked, ‘What would you think about exploring these themes, the style and spiritual similarities?’ And they were on board immediately.”

Butcher was already well acquainted with Backus. In 2003, he shot photos at Adams Ranch west of Fort Pierce, where the owner, the late Bud Adams, had several Backus paintings in his home. Adams told Butcher that Backus considered the ranch one of his favorite places to paint. “That made me smile,” Butcher wrote on his website, next to a print from his day on the ranch. “A fellow artist saw the beauty of Florida in his heart and wanted to share that beauty through his paintings.”

That Butcher photo from Adams Ranch is among the prints on exhibit, suggested by Butcher himself, Adams says.

Butcher will sign books at the Backus Museum Saturday, March 30, from 1 p.m. to 3 p.m. The Butcher and Backus show continues through April 28. The museum is at 500 North Indian River Drive, Fort Pierce.