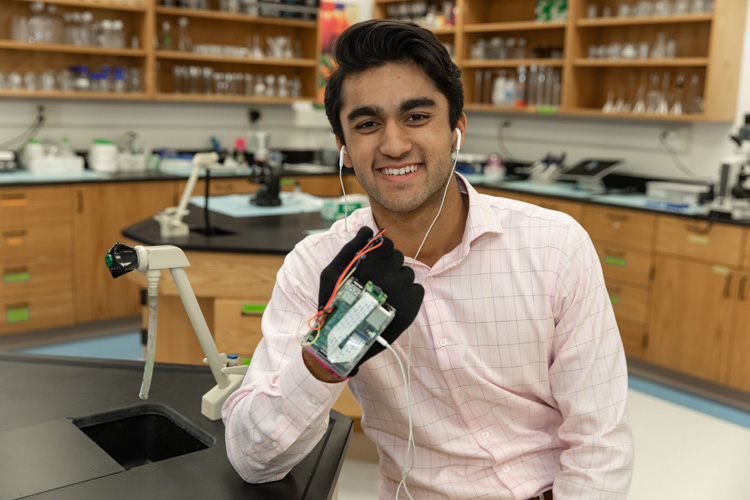

Saint Edward’s Upper School student Omar Shareef is offering a significant “Helping Hand” to the visually impaired through the use of an assistive-technology device that he has invented. The device is designed specifically to help the visually impaired and blind – as defined by the American Foundation for the Blind – by enabling them to hear what they cannot see.

The Helping Hand – Photos by: Denise Ritchie

“It has a camera on it,” Shareef explains. “You point it in the direction of different objects, faces or text, and the device recognizes items using various AI [artificial intelligence] algorithms.”

The Helping Hand is a glove that enables wearers to point to an object and press one of three buttons on the pointer finger to identify objects, faces or text. Since that the original design, Shareef has also created a handheld device and glasses.

He says there are similar products to his Helping Hand on the market, but they are costly ($4,500 to Shareef’s $50) and often cumbersome. Most importantly, in addition to being reasonably priced, his device can function without the Internet, meaning that anyone anywhere can “see” with their hands.

“I developed this so a visually impaired person can walk into a new environment and ‘see’ what’s around them, to give them a sense of independence,” says Shareef. “It originally started out as a research project for a science fair. But, given the overwhelming enthusiasm and a lot of the reactions that I got, I decided that it would be worthwhile to take it further.”

It was while visiting an orphanage in India with his father that Shareef first became aware of how difficult social independence can be for the visually impaired. He was 10 years old at the time, and the sight of children being ignored and jostled around stuck with him.

“In India, they don’t really have the infrastructure to help these kids go through their daily lives. I saw what a struggle it was for them, especially compared to the sighted kids,” Shareef recalls.

Six years later, Shareef was buddied up with a visually impaired student from the Wabasso School during Pal Day, and observed that his new friend was uneasy whenever he encountered an unfamiliar environment.

“He was anxious and I realized there has to be some way I can alleviate these issues for them.”

Shareef garnered an interest in technology and computer sciences in the fifth grade, acquiring coding skills with the help of a Raspberry Pi (a tiny computer used to learn programming).

“My sister, Sana, would come in and annoy me in my room. So, I attached the Raspberry Pi to my wall with a motion sensor and a keypad. As soon as she would open the door, it would make a buzzing noise until I entered the passcode. Kind of a sister deterrent,” says Shareef with a chuckle. Armed with that early technical expertise, he began to build a prototype device.

Omar demonstrates another prototype using eyeglasses

“I have a great background in computer science. I knew I could do something with what I know to help these people. So, I set out to build this glove,” says Shareef. “I love to create things, and my love for artificial intelligence, computer programming and science in general, goes beyond words.”

Because of his coding mindset, he says learning new algorithms wasn’t difficult, but he had no prior knowledge of artificial intelligence.

“So during the summer I went online, learned the various artificial intelligence algorithms, read different research papers on artificial intelligence and computer vision, and set out to build the device. What’s really crazy is that a lot of these algorithms weren’t even available two years ago,” says Shareef.

He began tinkering with the idea during the summer of 2017 as a research project, which he presented at the Regional Science and Engineering Fair hosted by the Education Foundation of Indian River County.

After taking top honors locally, Shareef went on to the State of Florida Science and Engineering Fair, again winning first place. Then it was on to the 2018 INTEL International Science & Engineering Fair in Pittsburgh, Pa., where he received third place.

The design of the glove is rather simple, says Shareef, explaining that the components include a minicomputer, a battery pack, camera and an audio output source (headphones or speakers). The key, he says, is that everything runs locally. It does not need an Internet connection or WiFi.

“If you’re relying on this device to tell you what’s around you in a place you’re unfamiliar with and suddenly you don’t have WiFi or Internet, that’s going to be a pretty big issue,” he explains.

Omar Shareef’s hand held Box prototype

The second-generation device has several improvements to original design – it has greater accuracy and speed, it’s more ergonomic, it can recognize 500 objects and it also has a panorama feature. Additionally, the facial recognition feature can be trained to recognize 400 different faces and is nearly instantaneous.

To test his product, Shareef consulted with students from the Lighthouse for the Blind, asking them to try out the glove and provide feedback. That first-hand perspective ultimately led to his developing handheld and eyeglass versions of Helping Hand.

“They didn’t like the idea of the glove because they rely heavily on the sense of touch,” explains Shareef.

Despite the recognition Shareef and his product have received from television and media publications, he remains focused on senior-year activities and college applications; he hopes to be accepted by Stanford because of its proximity to Silicon Valley.

He has also founded Second Sight, a nonprofit organization whose mission is to empower the visually impaired and blind by developing artificial intelligence technologies, allowing users to perceive their surroundings to increase social independence and mobility.

“The nonprofit will help me to facilitate the development and distribution of the device that I created,” he says.

To thank the various teachers, science fair judges, prototype testers and others who have helped him along the way, Shareef hosted a Dinner in Darkness event at the Pelican Yacht Club in Fort Pierce this past October.

Guests were plunged into darkness and challenged to eat their dinner in the dark; putting his sighted guests in the shoes of those with impaired vision or no sight at all.

“There are 253 million people who live with visual impairments in the world and 36 million of them are completely blind,” says Shareef.

His vision is clear: to put as many of these low-cost devices into the hands of the visually impaired as possible.