The exhibition “Paul Outerbridge: New Color Photographs from Mexico and California, 1948-1955” opened to the public in the Schumann Gallery at the Vero Beach Museum of Art on Jan. 20 and runs through June 3. While it is new to Vero Beach, the “New” in the show’s title is puzzling.

Organized by Pasadena-based Curatorial Assistance Traveling Exhibitions (CATE), the show has been available for public display since at least 2008, when it appeared in Ann Arbor, Mich., courtesy of the University of Michigan Museum of Art.

That was 10 years ago; so that part of “New Color Photographs” isn’t new, is it?

The exhibition was curated for CATE by William Ewing, an independent curator and author on photography, and Phillip Prodger, head of the Photographs Collection at the National Portrait Gallery in London, England. The 33 images they chose to include in the exhibition are representative of some 500 Kodachrome images taken by American photographer Paul Outerbridge between 1948 and 1955.

That means that the images in the show, taken at least 63 years ago, are not new, either.

Outerbridge died in 1958, before he could realize any of the shots he took as photo prints. All of the color prints in the show were created in recent years. The original collection of transparencies, along with the rights to reproduce them, were purchased nearly 40 years ago by the founder and current CEO of Curatorial Assistance (and its non-profit arm, CATE), Graham Lowe. The seller was the photographer’s widow, Lois Outerbridge Cunningham.

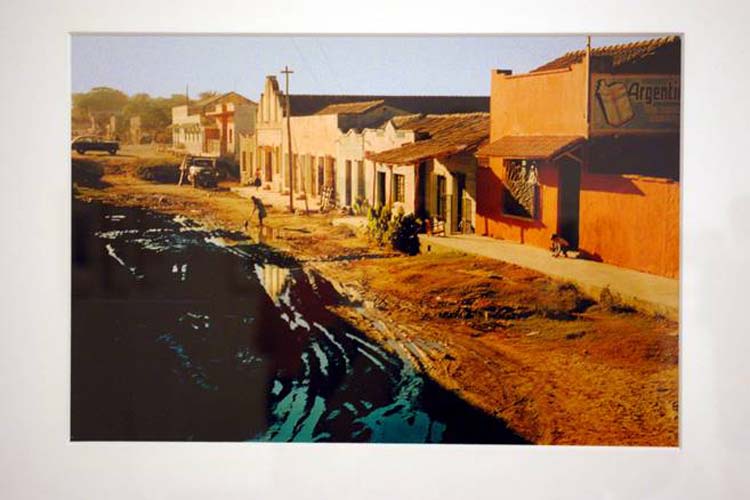

The collection’s subjects are scenes of people and locations in and around Laguna Beach, Calif. (Outerbridge’s home for the last decade of his life) and in Mexico – especially the seaside resort town of Mazatlán. The 1950s time period is readily apparent in the clothing, architecture, cars and leisure activities pictured. Outerbridge, with his commercial and fashion photography background, had an unerring sense of style in depicting sophisticated women in smart outfits, bathing beauties and chic watering holes. Those pictures will have some members of the VBMA audience reminiscing about their own travels in that time to those places, while the rest of us will merely wish we could have been there.

What then, is new about these “new color photographs?” If you substitute the phrase “seldom-seen” for the word “new,” you will be getting to the heart of the matter. These photo images, hidden away until after the artist’s death, have not found the audience that his widely reproduced early work has.

At this point you might ask, “Who was Paul Outerbridge, and why should we care about his pictures?”

Paul Outerbridge Jr. was born in 1896 to an affluent family in New York City. After service in World War I (briefly with the Canadian Royal Flying Corps and then with the US Army, where he took his first photographs) Outerbridge studied in New York at the Clarence White School of Photography. His first fine art photographs were nudes and still life printed on paper in platinum an expensive and very permanent black and white printing process. He often pre-visualized his photos’ compositions in sketches prior to tripping the shutter on his carefully lit studio arrangements. Although composed of common objects, Outerbridge’s still-life pictures are celebrated as modernist abstractions.

Commercial commissions for product illustration followed, and Outerbridge’s work began to appear in Vanity Fair and other magazines. He went to Europe in 1925 and lived in Paris for several years, where he photographed for Paris Vogue. There Outerbridge met fellow photographers Man Ray and Berenice Abbott, as well as Marcel Duchamp, Pablo Picasso and other members of the avant-garde. Outerbridge returned to New York in 1929, where he continued his successful commercial career.

To illustrate his early work, the current exhibition has on view a 1931 still life from the collection of the late Raymond Kassar, a Vero Beach resident. It was something of a coup for the VBMA to obtain the loan of one of the collection’s prints. In the past, objects from that substantial collection of works by renowned photographers have only rarely been displayed to the public.

Titled “Consciousness,” the black-and white gelatin silver print presents the forms of a cone and two eggs precariously perched on a narrow ledge. An original print signed by Outerbridge, the image owes a debt to the nascent Surrealist aesthetic that he would have experienced in Paris.

After Outerbridge’s 1929 returned to New York, he experimented with the technically difficult tri-color carbon process, which he mastered and made his own. This made him not only more desirable as a commercial photographer; it also gave a new dimension to his fine artwork and especially to his depiction of the female nude.

If you do not know Outerbridge’s early fine art photography, you do not know Paul Outerbridge. The handsome hard cover catalog for the show (a copy of which is available for visitors to peruse in the gallery) reproduces two examples of these: “Avocado Pears,” a still life from 1936, and “Descending Night” of 1935. The latter is, perhaps, Outerbridge’s most lyrically beautiful nude. It is on the strength of iconic images such as these that Outerbridge fans will go to see the current exhibition, in hopes of viewing the artist’s late images, printed in the now rare carbon color technique.

Alas, this is not the case. While two of the photos in the show are executed as tri-color carbon prints (impeccably printed in 2008 by Todd Gangler of Art and Soul Photo in Seattle) most are printed (beautifully) in the modern color digital technique, as well as a few dye transfer prints, which the digital color very much resembles.

The tri-color carbon prints are “Woman with Turquoise Dress, Laguna Beach, California” of c. 1952 and “Carnival Carriage, Mexico” of c. 1950. The images do not disappoint. The latter depicts a party of masked and begowned revelers seated in a black carriage; the former shows a bleached blond in a satin evening gown whose charms are fiercely compressed by a tight bodice. The woman’s half-length figure is placed to voluptuous advantage in front of an industrial-looking louvered window. It is her sun-hardened squint and parted red lips, however, which transform a flesh-and-blood being into an allegory of louche sophistication.

Off all the pictures in this show, it alone suggests the fetishistic nature of Outerbridge’s depictions of women in his 1930s heyday. By all means, look up some of his classic nudes and still-life compositions before you visit the show at the museum. It will bring a depth to the late work that, for all its technical virtuosity and picturesque subject matter, it would not otherwise have.