Melbourne’s Ruth Funk Center for Textile Arts at Florida Institute of Technology is out to prove that the beauties of science can be visually as well as intellectually stimulating. The center’s current exhibitions provide compelling evidence for that theory.

“Radical Elements” is a traveling show from Studio Art Quilt Associates, a non-profit organization devoted to the development and promotion of quilting as an art form. Curated by quilt artist Jill Rumoshosky Werner, the invitational exhibition challenged artists to create 40 quilts based on elements in the periodic table. The table arranges the 118 known elements in order of increasing atomic number.

Another traveling exhibition, “A View Within,” is the sixth in a series from California-based fiber artists Paula Chung and Karen Rips. The artists have collaborated on works based on X-ray and other medical scans of the human body. The show combines both recognizable and abstract imagery in which timeless beauty subsumes the mortal coil.

The shows are a must-see for anyone who enjoys being surprised, delighted, awestruck and moved by art, but you must hurry: next Saturday, Aug. 27, is the last day to view both shows.

The large-scale artworks in “A View Within” find their source in the coldly informative images of modern medicine, but Chung and Rips’ art insists on the humanity of their subject matter. By portraying the delicately personal inner workings of our insides in dense machine embroidery and quilting on hand-dyed silks and cotton, the artists remind us that these organs, tissues and bones belong to real people – just like us.

In fact, some of the imagery in the show was taken from the X-rays, MRIs, CT scans and ultrasounds of Chung and Rips’ friends and family members, who granted the artists permission for their use, says Florida Tech’s director of collections, Sarah Smith.

Using her own style, each artist “would work from the same image and not discuss with the other what she was doing. When the pieces were finished, Chung and Rips would come together to see what they had independently created,” Smith notes.

Many of Rips’ works are abstract compositions in shades of ivory, gray, charcoal and ocher that transmit something akin to the robust serenity of Zen calligraphy. A glance at Chung’s more literal interpretation in each thematic pairing reveals the common source of the imagery.

A few, but not all, of the pictures in the show carry the emotional weight of a serious medical condition. Smith mused it would be interesting to have a radiologist’s reading of the exhibition.

One of the most compelling pairings in the show centers on an MRI of the human brain seen through the top of the skull, looking a bit like a walnut in a circlet of shell.

Chung calls her interpretation “Brain Tumor.” In her hands the image becomes a verdant island protected by a narrow reef; on the island’s east side the tumor, blue as the sea and shaped like an inlet, penetrates the forest of the brain.

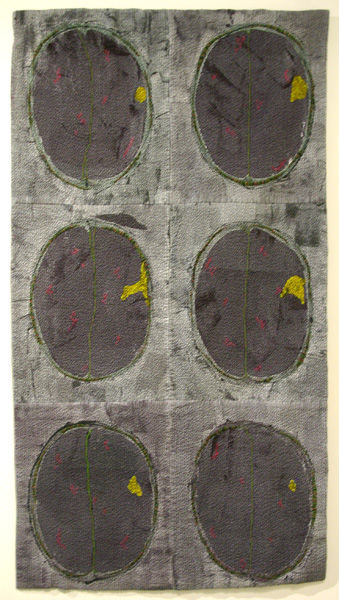

Rips multiplied the image by six and stacked it three high and two across. In contrast to Chung’s thick mats of embroidery, Rips uses fine furrowed quilting, puckered auras that shimmer in and around her subjects. In “Brain MRI,” her backgrounds and brains are different shades of gray mottled with hot spots of deep pink and, for the tumor within each ellipse, green-gold.

Segueing to “Radicals Elements,” don’t despair if you fell asleep during your college chemistry classes. The show takes a mostly light-hearted look at its heavy subject matter.

The possible exception is Daren Pitts Redman’s fearsome “Uranium 235.” The quilt bears a photo-based representation of the hydrogen bomb exploded over Bikini atoll in 1954. Thread-painted on black cotton in radioactive reds and oranges, the picture, long a visual cliché, still has the power of a sucker punch. You can’t defend yourself from its beauty, much less its ominous meaning.

The artists in this exhibition were to refrain from using fabric and thread in their quilts and to instead find alternatives not only for the quilt’s layers, but for the ways of fastening them together.

Gay E. Lasher’s sculptural “Last Rays” is bolted together layers of aluminum sheets. The first is laser-cut in a crisscrossing composition, while the second bears an embossed pattern of crumbly-edged squares. Both layers are solidly inkjet-printed with color, creating the off-message effect of tangled, rust-streaked girders before a concrete block wall.

Perhaps a better literal interpretation of an element is found in Trisha Hassler’s “The Irony of It All Was Not Lost on Her.” The pun tribute to iron is “exceptionally heavy,” says Smith.

It was also the weightiest to hang.

The lushly textured object includes a reclaimed carpet pad, a sheet of steel, snakeskin, palm fronds and 26 hand-cut steel discs (iron is element No. 26 on the periodic table). The discs, arranged in three vertical rows, might put you in mind of a primitive almanac produced by some remote cargo cult.

Free association runs rampant in the show. “The Salt Flats” by Jeannie Palmer Moore combines traditional quilting techniques with offbeat materials – plastic bags, yogurt lids, ironing board fabric. Moore represents sodium as a vast snowy landscape of salt with two tiny sleds parked on a distant ridge. The silhouette of the little Morton salt girl strides along the scene, her open umbrella shelter from a snow-filled organza sky.

For this writer, the experience at the Funk was enriched by two knowledgeable docents, Diana Newman and Flo Poor. They really knew their arsenic from their einsteinium.