Jay Williams likes to keep a low profile, even though as curator of the Vero Beach Museum of Art, he gives talks to the public and tours to the press, and is present at openings and fundraisers.

So when his name showed up in a nationally syndicated Associated Press article that ran in the daily paper here, he quietly laughed it off when few seemed to notice.

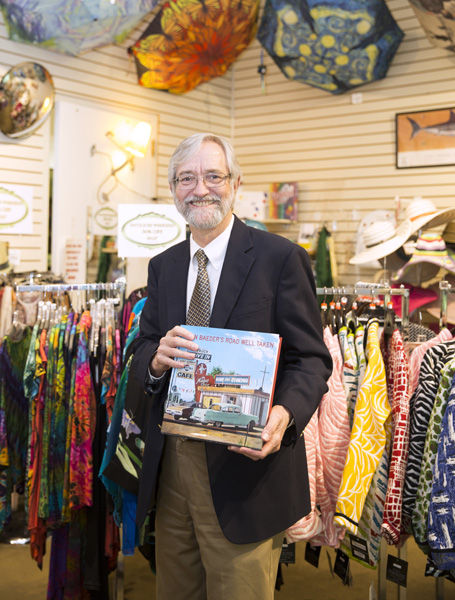

Midway down under the AP headline: “Big Books Make Great Gifts for the Holidays” was “John Baeder’s Road Well Taken,” an art book about the well-known painter of diners and other Americana.

That name alone should have jumped off the page to members of the museum, which is featuring Baeder’s photography in an exhibit opening next week.

Even more remarkable was the book’s author: Jay Williams.

Wednesday, Vero has a chance to make up for its oversight. Williams and Baeder will be honored at a book-signing and reception at the museum on the eve of the exhibit’s opening. The signing will immediately follow a talk by the pair, accompanied by projected images, beginning at 5 p.m.

The large and stunning book was published in October by The Vendome Press and distributed by Abrams, both top names in the world of art books. Beyond the AP’s recommendation, the 270-page volume with 283 images has garnered mentions in The Chicago Tribune, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, The Salt Lake Tribune and the prominent online travel site, Atlas Obscura.

In the Vero Beach Book Center and museum gift shop, one look at the cover – a painting of two vintage cars in front of a roadside café – and the broad appeal that earned the book a spot on that AP list becomes obvious.

For Williams, it is the back cover that makes him grin – a 1970s photo of the same painting but with Baeder standing behind it. Baeder, who turned 77 on Christmas Eve, was in his early 30s in the photo, wearing a modified Afro, a denim shirt, khaki trousers and a very wide belt.

A man of average height, he is barely taller than the painting. His oils are as wide as 4 or 5 feet; his watercolors, equally detailed, are smaller.

“We got the designers to go along with putting that photograph on the back cover,” Williams says. “It gives you an idea of the scale.”

It also gives an idea of the era when it first occurred to Baeder that diners were art-worthy. Today examples of Baeder’s works are in the permanent collections of the Cooper-Hewitt Museum and the Whitney Museum of American Art.

“I was a grad student in 1973 and ’74 at the University of South Florida when John was making a big splash with his diner paintings,” Williams recalls.

After five years of working together on the book, Baeder and Williams have forged a friendship that is not likely to dissipate. Williams first met Baeder when he curated a retrospective of his works in 2007 at the Morris Museum of Art in Augusta, Ga. The Morris, with its focus on art of the South and in particular folk art, was a natural link to Baeder, who was raised in Atlanta, educated at Auburn University and currently lives in Nashville.

Before the Morris, Williams worked at South Carolina’s McKissick Museum, where he studied material culture – how everyday objects of people, like tools and furnishings, serve to tell a story.

That background very much played into Williams’ instant connection with Baeder. “We hit it off,” says Williams. “He felt I understood his work.”

Baeder had had a successful career in the 1960s as art director of several large New York ad agencies. But he has always loved small towns and collected thousands of vintage postcards showing commercial buildings and street scenes.

At the same time, he was shooting photographs of not only diners and street scenes, but hand-painted signs. With their quirky hand-lettering and often guileless messages, they fill an early section of the book. In one early photo, a pair of men’s shoes in a shop window bears a small note: “This is it Man!”

Williams has read them all, of course, but reading them again, he still has to laugh. “Health Camp,” he reads from the sign over a diner. “Isn’t that the greatest name for a fast food place?”

As an artist himself, who as a boy used to paint from his family’s photo slides, Williams appreciates Baeder’s input in transforming photographs and post cards into paintings.

“These paintings are really abstractions. People take it for granted: ‘Oh, he’s just copied a photograph.’ It’s anything but copying. There’s a tremendous amount of artistic decision making,” Williams says. “You change the scale, you decide where edges are, how the shadows are handled, what the sky looks like.”

Williams’ hand scans a cotton candy-colored sky and its reflection in a parking lot puddle. “He’s creating a whole harmony of color here.”

After their discussions at the Morris, Williams and Baeder continued emailing, their friendship deepening as they pursued a mutual and profound interest in Jungian psychology as it relates to the artistic quest.

“We connect on a lot of levels, but that level is the most important,” says Baeder, reached at a Nashville gallery currently staging his retrospective. “He picked up the inherent spiritual aspect of my diner paintings real quickly. That was important to me.”

Approached to write a book about Baeder’s life and work, Williams made his first visit to Nashville in 2010 and recorded hours of conversation over the course of two days, seated at the old diner tabletop pictured in the book, etched with thousands of initials.

“It’s impossible to describe the interior of John’s house,” says Williams. “It’s like a Baeder museum. Every inch has either hand-painted signs, folk art, figurines, or model cars. They say the sun’s energy feeds off all the molecules in the star. That’s like John’s energy: he’s fed by all the energy of his collections.”