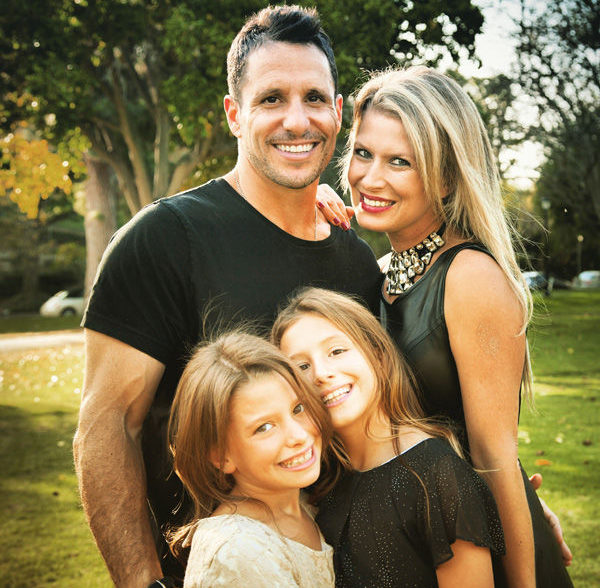

It wasn’t easy on Brett Tabor’s young family when the aspiring screenwriter moved them from Vero to L.A. “We’ve got to pull the ripcord and get out there,” he told his wife, Andrea, who had formed close friendships after almost a decade in Vero Beach.

But Tabor was putting himself right where he needed to be – and his eight-year obsession with making “The Man Who Made It Snow,” a movie about a Miami cocaine kingpin, has led to the signing of three huge names in Hollywood: actor Jake Gyllenhaal, director Antoine Fuqua, and now, Harvey Weinstein, whose company just pre-bought U.S. distribution rights.

The subject of the upcoming film: Max Mermelstein, mastermind of the Medellin drug cartel, the lone American in the organization’s inner circle, and according to prosecutors, the single most important informant in the history of the U.S. war on drugs.

It is a staggering Hollywood success story for Tabor, 42, a guy who could have comfortably stayed in Vero raising a family and working in his father’s business; he’s the son of prominent Stuart-based developer Marty Tabor.

He’s also the son-in-law of Vero’s Vince Nelson, Andrea Tabor’s father.

Born in Kendall, Tabor left Miami in the 1990s to try his hand at acting in L.A. In 1999, Tabor moved to New York and got some off-Broadway roles.

He also fell madly in love with Andrea Nelson, and they ended up marrying.

With a baby on the way, he came home to Florida in 2004. The couple bought a place in Baytree in Indian River Shores.

While the effervescent Andrea quickly made friends among beachside moms, Brett helped his father manage properties.

But his mind was still on movies.

Then came his glimpse of the photo of Mermelstein in the documentary film “Cocaine Cowboys.”

As he told Miami New Times, he walked out of the theater asking himself, “Who is this Max guy?”

Tabor ordered a copy of Mermelstein’s out-of-print autobiography.

What he discovered was “not your average story about a drug dealer who wanted to own the world,” Tabor says. “It was your quintessential ‘fish out of water’ story. This was a nebbish Jewish guy who was duped into engineering all the transportation and distribution for Colombia’s Medellin cartel. He was their Oz behind the curtain and was looking for a way out since the day he started.”

Convinced it had the makings of a blockbuster movie, he arranged to buy the rights for $9,000.

Now the question became, where is this Max guy?

First stop was the Miami office of federal prosecutor Dick Gregorie. He let Tabor pore through boxes of documents from the case against Mermelstein, a Jewish-American hotel engineer turned multi-millionaire coke smuggling mastermind.

Mermelstein had first come to public attention as the man who sold 26 kilos of cocaine to automaker John DeLorean in a federal sting.

He subsequently served only two years in prison after offering devastating testimony that brought down the cartel – and led to the arrest of Manuel Noriega.

In 1986, released from prison but with the cartel’s $3 million bounty on his head, Mermelstein went into hiding with federal protection, along with a record 16 family members.

After the death of the cartel’s leader, Pablo Escobar, Mermelstein left the Witness Protection Program but continued to use an alias.

And he stayed in contact with the prosecutor, Gregorie, who called him on Tabor’s behalf.

Gregorie wasn’t optimistic. Max had turned down numerous requests for interviews, including from Time magazine and 60 Minutes.

On the way back to Vero from the Miami prosecutor’s office, Tabor’s phone rang: it was Max.

Tabor found him in Frankfort, Ky., dying of bone, liver and lung cancer – and still chain-smoking.

For five days, Mermelstein talked into Tabor’s tape recorder in a Marriott hotel conference room.

When Tabor mentioned he was from Vero, Mermelstein laughed.

“He said, ‘Vero was one of my biggest windows,’” recalled Tabor in a 2010 interview with 32963.

By windows, Mermelstein was referring to gaps between radar. Mermelstein also told Tabor he’d been here scouting for entry points, drop zones on remote ranches, and rural roads they could use for runways.

Tabor co-wrote the screenplay with Michael Kingston, a screenwriter Tabor calls “nothing short of amazing,” whom he met through Andrea.

By the time the script was finished, Antoine Fuqua was already on board.

“The greater feat than getting him was getting into the agency,” Tabor says.

For that, he had a strategy: to talk to one particular “huge, mega” entertainment lawyer in L.A.

From his home in Baytree, he repeatedly called over the course of two weeks, pleading with the receptionist, to “just give me 30 seconds on the phone.”

Finally, he got through to the lawyer.

“I gave him a sincere pitch. There was this pregnant pause, and he said, ‘I just want to know how you found the guy in the Witness Protection Program.’”

Then he added, “I’d like to meet you tomorrow morning.”

Tabor ate the dinner Andrea had on the table, caught the red-eye flight from Orlando and was in the lawyer’s office the next morning.

“He said I was the most enthusiastic guy he’d ever worked with,” says Tabor, laughing. “He read the script and said, ‘Look, I’m not an agent, but I like your energy.’ And he recommended me for a simple sit-down at C.A.A. and the story stood on its own merit.”

Once he met with an agent, he says, “All I had to pitch was Antoine.”

With shooting set to start later this year, Tabor is already working on new projects – five at once, he says.

A lawsuit over the script has finally gone away, he says. And with all the news about the film, he’s got something in production on the home front: they’re expecting a third child.

Though they’re happy in Westwood, their L.A. neighborhood, Andrea still gets wistful over Vero, he says.

“She loves Vero like you wouldn’t believe. That’s where she raised her babies,” says Tabor. “There’s no question we’ll have a second home there. We do call it home.”