If it was hard for the family to convince architect Jim Gibson to retire, to close his practice on Azalea Lane last year, maybe it was because his love for the job was revived every time he stepped outside.

Like so many residents and visitors to Vero Beach, Gibson took great pleasure in the town’s visual serenity, much of it cast in a mold he formed.

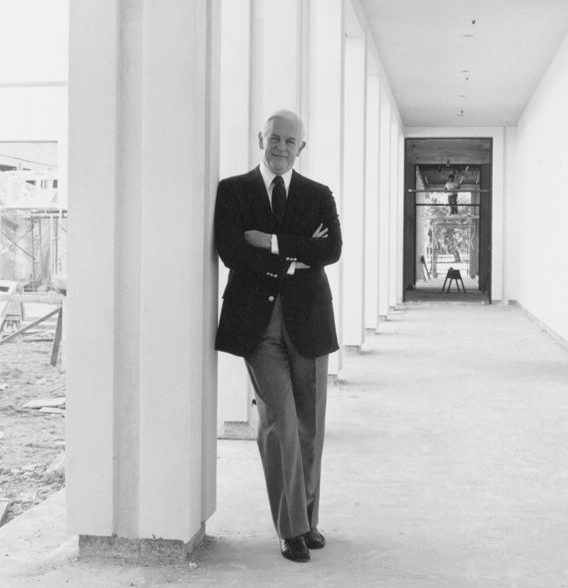

Gibson, the original resident architect of the John’s Island development, died Aug. 24 at the age of 92. He is credited with giving the barrier island’s built environment its identity. Classical Georgian-style buildings that line the beach’s tidy commercial district; the landmark art museum and theater in Riverside Park that he designed for free; the elegant gatehouses and clubhouses of its oldest neighborhoods and hundreds of their homes that bear the mark of Gibson’s vision for Vero.

Until the moment he shuttered his cozy offices and reluctantly let go of his small but devoted staff, clients still came to Gibson to put their projects to paper: a new drawing room, a bigger master bath, or a renovation that would turn a dated house into a coveted property and, more importantly to Gibson, a comfortable home.

To the end, Gibson did all his design by hand; he never learned computer-assisted design, or CAD – the ubiquitous software used today that generates blueprints with an entirely different look, says Gibson’s son Randy, a longtime professor of computer science at Indian River State College who studied theater design at Yale.

Vero was a sleepy town of 5,000 when Gibson arrived in 1969. Happily for the rest of its residents, then, now and in the future, he was content to stay despite an important early career in a large Grosse Pointe, Michigan, practice. His portfolio included the building that houses the Department of State in Washington, DC; two major wings of the vast Detroit Institute of the Arts; and the Henry Ford Centennial Library on the campus of Michigan State University.

“But that wasn’t really where his heart was,” says Randy of his dad’s commercial buildings. “He really enjoyed residential. He liked working with people to produce something that would create joy and comfort in their lives.”

Gibson knew nothing of Vero when he arrived here as a recent widower with three sons to raise. “Vero was absolute news to me,” Gibson said in a 2009 interview with Vero Beach 32963. Fortunately for him, Randy points out, he arrived as a bachelor “and there weren’t many bachelors in Vero.” That he was genteel, funny and handsome didn’t hurt.

He also was well-connected, even if he hardly knew a soul.

His Grosse Pointe neighbor, Llwyd Ecclestone, had just undertaken his second luxury gated community, John’s Island. He had earlier asked Gibson to move south to design Lost Tree Village in Palm Beach County. But his wife’s health was failing; she had multiple sclerosis, a diagnosis Gibson knew at their marriage but never revealed to her. When she died in 1967, Gibson was left to raise their three sons.

In Michigan the family lived in a huge 31-room Italian Renaissance mansion with half-a-dozen bathrooms and three kitchens that Gibson himself had resurrected from “complete collapse,” his son says, including a caved-in roof.

“He spent 15 years – my entire life there – redoing that house. That was his golf game,” Randy Gibson says. For his own family, “he never built a house that he designed,” Randy said. Every home was a re-do, and when he was done, every home was gorgeous, including several historic residences in Charleston, SC, where for years he kept a second home.

When Gibson bought a tree farm in the Irish Hills of southern Michigan as a place to take his boys on weekends, he brought them all out to see it. “There was this old ramshackle place, just a few toothpicks, really,” Randy recalls. ”We said, ‘You’re going to tear that down, right?’ And he said, ‘Oh, no, that’s got potential!’ And we went out there with nails and hammers and rebuilt the whole thing from the rafters down.”

While Gibson knew how to wield a hammer and saw, his hands were at their best playing music. The family’s first home on Camino del Rio included a music room big enough for his harp and his two grand pianos, one of which was a 1923 Steinway concert grand that he donated in 2009 to the Vero Beach Museum of Art.

An ardent supporter of Vero’s musical organizations, he was former president of the Atlantic Classical Orchestra. He played violin nearly all his life – until his neck wasn’t strong enough to hold it in place, his son said. That was only a couple of years ago.

By then, Randy and his wife Toni had started taking turns dropping in on his independent dad who lived alone on Gayfeather Lane. Every evening and every morning, they made sure he safely negotiated the stairs and stayed a while to enjoy his company. “Physically he was doing very well,” said Randy. “He had friends come by and visit, and he was not a person that minded being alone – he enjoyed it. He had his books and he had his music.”

For nearly two decades, Gibson led the violin section for First Baptist Church’s annual production of the Messiah. He was also a major fan of theater, participating in countless shows with the Vero Beach Theatre Guild including a role in “My Fair Lady” – he played a friend of Eliza Doolittle’s father. He met his second wife Suzan at a Guild production; she died in 1998. His two older boys worked on the crew at the Guild; the youngest son, James, also acted.

Gibson credited his parents with showing him the beauty in life and instilling a love of design, art, antiques, gardening and music early on. He also had a great sense of humor, Randy says. “He was particularly fond of the ‘shaggy dog’ stories that go on and on before the punchline.”

Born in Oregon, Gibson earned a degree in music first before joining the Army. He fought as a combat infantryman in the Battle of the Bulge and the Rhine Crossing, experiences that taught him to enjoy each day, his son Jay said at a memorial mass Saturday at St. Augustine of Canterbury Episcopal Church. “I can’t remember him complaining ever, and that was a choice he made every day.”

“He judged people not by his standards but by their potential,” said Randy at the service. That sentiment was echoed by stepson Frank Brown, who lauded Gibson’s tolerance and patience and said he “never heard him say a mean word ever.”

For the family, Gibson’s passing was particularly difficult due to the death of his oldest son Graeme in Independence, Missouri, less than three weeks earlier. In his 20 years in Vero, Graeme Gibson trained pilots at FlightSafety, opened a school in computer repair and became an expert in technology.

Graeme was 18 when his father decided to move to Vero. “He worked on each of us individually,” says Randy. “He was commuting for a few months between Michigan and Florida and on each of those trips he would bring one of us. He would try to find one thing that interested us.”

Luring Graeme to Vero, Gibson had taken him to Indian River State College, then a junior college. The idea, recalls Randy, who ended up teaching computer science there for the past 30 years, was to give Graeme an idea of classes he could take.

The youngest brother Jay, who went on to teach at St. Ed’s, was only 10 then, and not hard to persuade, Randy says.

Randy, at 15, had a soft spot for restaurants, so his dad took him to the Ocean Grill, one of his favorite places.

“I’ve always been intrigued by the pure imagination that went into that building,” Gibson said in the 2009 interview. “That wonderfully wavy floor. You almost get drunk just going to your table.”

Randy Gibson hopes for a second memorial service, once Gibson’s clients, so many of them winter residents, are back in town.