Two books of national stature are benefiting the Save the Chimps sanctuary in Fort Pierce, and offer readers both a factual account and a fictional tale of captive apes, their ordeals and their defenders.

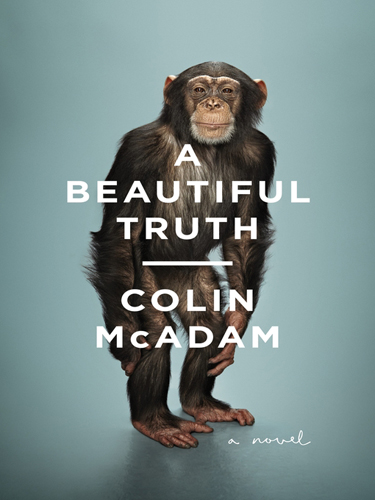

“A Beautiful Truth,” by the Canadian novelist Colin McAdam, is a carefully woven together work of fiction about a chimp in Vermont adopted by a childless couple and raised as a coddled human baby would be, but who ended up tormented at a research lab in Florida.

The other book, “Opening Doors,” by the nationally-known nature writer Gary Ferguson, is an overview of Save the Chimps, and includes biographical information of both the late Carole Noon and of the beloved chimps she rescued. The animals’ abuse, their enduring personalities and social interactions as they were reintegrated from isolation into groups at the sanctuary were the subject of hundreds of narratives she emailed to her friend and benefactor, Jon Stryker of Palm Beach.

Sales from both books, available now at the Vero Beach Book Center, are contributing to the rescued chimps, a cause dear to many in Vero, where for the past five years a “Chimps’ Kitchen” food-tasting fundraiser has been staged in the fall at the Vero Beach Hotel. All proceeds from “Opening Doors” benefit the sanctuary. And “A Beautiful Truth,” first published in 2013, is donating $1 for every copy sold, in conjunction with its release in paperback last week.

The coffee table-worthy “Opening Doors“ uses abundant descriptions by Noon herself (she died of pancreatic cancer in 2009) as well as stunning photography to tell the history of a group of 141 chimps. First acquired by the U.S. Air Force for use in the space program, they were farmed out to a New Mexico biomedical research lab for experiments, presumably for the rest of their lives. Through Noon’s and Stryker’s efforts, they were finally freed from their tiny cells starting in 1997 and brought to the 150-acre Fort Pierce sanctuary. Today there are nearly 250 chimps in Save the Chimp’s care, making it the largest facility of its kind in the world.

McAdam’s novel “A Beautiful Truth” has as its protagonist a chimp raised as a human, then sent away to a lab when he frighteningly outmaneuvers his human family.

Much of “A Beautiful Truth” is told through the invented language and imagined thought processes of the chimps in captivity. McAdam, a masterful writer, creatively omits punctuation to jar the reader into the similar-yet-foreign minds of apes. . As such, it is bound to bring to mind the mauling of Charla Nash by the pet chimp Travis in 2009, an incident that provoked a nationwide uproar about keeping chimpanzees as pets. (Noon noted those chimps were always the most difficult to reintegrate into the Save the Chimp groups because of how oddly they had been raised – “like mini-humans,” she said.

The main character is a chimp named Looee, who is captured in Sierra Leone as a baby, and sold to a childless Vermont couple, Walt and Judy, as a way to fill the void in their lives from Judy’s infertility.

It is the 1970s, a time when, as McAdams points out, exotic pets were not closely regulated. The couple decides to keep the animal in their home, uncaged, and the raucous domestic scenes that fill the first part of the book foreshadow the inevitable once the chimp grows menacing.

The dual story lines develop in more or less alternating chapters, a technique that serves to unite the two species, or at least show just how similar they are.

Slowly Judy, the “mother” of Louee, is ostracized by friends, particularly when Louee becomes sexual. (There is plenty of chimp sex in this book.) But she and her husband love Louee and do their best to forgive his ways, even as they gloat over his human-like “accomplishments,” never mind that for Looee, such milestones are not only unnatural but self-sabotaging.

Looee’s “chimp”-ness is thoroughly adulterated by his human coddling and constriction. He is then sent to a lab to live because he is too hard to control. Now we see a whole other side of him, as he interacts with other chimps in the unspeakably abusive setting of the lab.

We learn about the social dynamic of the lab chimps through the chimps’ own eyes and narrative voices. When Looee ends up joining them, the interactions becomes as emotional as the human drama in Vermont. It is an achingly difficult story to become truly engaged in, partly because of the culpability of our species, and partly because the chimp, so similar to humans, sometimes reacts in humanly reprehensible ways, and no more so than when he is subjected to the brutally degrading conditions of the lab.

For readers who know something of the Save the Chimps sanctuary, there are familiar scenes: Louee painting at an easel with his owner, Judy painting on the other side. (Save the Chimps benefits often involve the sale of paintings made by the rescued chimps themselves.) Acclimating lab chimps to one another reminds us of Noon’s patient efforts assessing chimps’ personalities before finally allowing them to roam together on their island homes.

There is endearing mischief, as in the time Louee slips out of the couple’s home one night and raids a neighbor’s refrigerator. Walking home through the woods, he marvels at the moon, not unlike Noon’s rescuees on their first night outside their lab cages, when they hooted and howled in amazement all night long.

McAdams leads us down a narrow moral line then moves it sideways, exculpating the captive beast for horrors worthy of the human death penalty, rightly of course.

McAdams says he was inspired to write the book after seeing a small chimp sanctuary near Montreal, run by Gloria Grow, a friend of Noon’s.

“Over time, Carole became kind of our alpha leader,” she says in “Opening Doors.” “She had this vast amount of knowledge, this way of thinking that was extremely valuable to our efforts.”