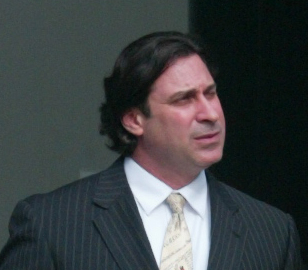

INDIAN RIVER COUNTY — Criminal court Judge Robert L. Pegg shook his head in disbelief recently as he pondered a particularly weird situation in a local theft case during a hearing. “This is the strangest thing I’ve ever seen,” Pegg told criminal defense attorney Bobby Guttridge.

“Yeah, it’s odd,” agreed Guttridge.

Pegg held the hearing in the Dustinn Keeling grand theft and worthless-check writing case because Guttridge asked for “a statement of particulars” – details of what led to a criminal charge against his client, which names Guttridge, himself, as one of Keeling’s victims.

Keeling, the former 20-year-old fund-raising chairman of the Haiti Clinic Foundation, is charged with stealing more than $20,000 from the Vero Beach nonprofit, which provides medical services in the slums of Port au Prince.

He is also charged with stealing more than $6,000 from the North County Republican Club while he was the club’s president.

But the charges didn’t cause a seasoned judge to marvel at the oddity of the case until Guttridge became Keeling’s attorney of record after the suspect’s arrest in July.

Then, two months later, Guttridge was named as a victim in the charges.

Count Number 12 accuses Keeling of criminally using Guttridge’s personal identification information without Guttridge’s knowledge to steal money from Keeling’s aunt.

The back story, according to a police investigator and discovery records, is that, months before his arrest, Keeling allegedly told his aunt that he needed a check for $10,000 to give to his attorney Bobby Guttridge as collateral.

Guttridge would hold the check for a few days and return it without cashing it, Keeling allegedly told his aunt.

Instead, Keeling gave the money to the Haiti Clinic Foundation as partial payback to try to stop them from going to police.

In other words, Keeling allegedly used Guttridge’s name to steal from his aunt.

At last week’s hearing, Pegg told Guttridge to talk to or depose Indian River Sheriff’s Office Det. Milo Thornton to get the details of how he – Guttridge – may have become a victim of his own client.

While it is not clear that Guttridge was Keeling’s attorney at the time Keeling got the check from his aunt, Guttridge said when he began advising Keeling was not something anyone but Keeling and him could know.

After the hearing, Assistant State Attorney Christopher Taylor said that because Guttridge would be called as a witness against his client, the attorney needed to recuse himself from the case.

“Bobby Guttridge will have to beg off of this case sooner or later or he’ll have a conflict,” said Taylor.

But Guttridge said that the police investigator and Taylor could not prove that Keeling illegally used his name without his knowledge.

“I could’ve given Dustinn advice about the check. They have no way of knowing whether I did or not,” said Guttridge.

“What I talk to my client about is a privileged communication,” said Guttridge. “I’m not saying whether I advised him or not because my conversations with my client are no one’s business, but ours. That confidence is at the very heart of a client-attorney relationship.”

Guttridge maintains he has no conflict because he can’t divulge information about his conversations with his client.

On the other hand, he concedes, the count may stick.

“If it does, I may have to withdraw,” he said.