VERO BEACH — Tucked into the intimate Stark Gallery, the smallest of the exhibit spaces at the Vero Beach Museum of Art, is a grouping of six pieces that taken together offer a fresh look at an iconic image: the tree.

A video installation cordoned off behind a black curtain, and five paintings and photos fill the space.

The Vero Beach Museum of Art’s newest exhibition takes a fresh look at one of the art world’s most iconic images.

“Inspired by Nature: Celebrating the Beauty and Complexity of Trees” features six very different works by five contemporary artists, all part of the museum’s permanent collection.

These “tree portraits” are inspired by real trees – majestic, weeping in the rain, or dancing through the seasons.

Surely, the “sexiest” of the bunch is the ravishing video installation, “Fly to Mars, 5” by the video and new media artist, Jennifer Steinkamp.

New media art is a genre of artwork using technologies such as digital art, computer graphics, and computer animation.

The prolific Steinkamp, who lives in Los Angeles, and teaches at UCLA, is one of the hottest such artists in the country.

“It can be hard for the older, more traditional art community to get their heads around this,” warns Joe Ellis, public relations and marketing coordinator for the museum. “This is art with no canvas.”

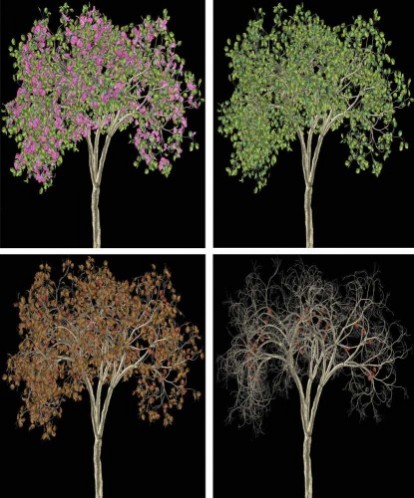

The video projection is of a maple tree cycling through the four seasons.

The tree flowers in spring, leafs greenly in summer, morphs into rusty reds in fall, and becomes bare as a bone in winter.

Rather than a single image, this is a composite of many natural movements made by trees.

“The way the branches and leaves move is patterned on scientific analysis of real trees,” says Ellis.

“Fly to Mars, 5” is a greatly simplified and flattened image of a maple tree that moves like a ballet dancer as it morphs through the seasons.

A living, breathing work of art, it has beauty and mystery, yet is completely accessible — no need to understand computer code to enjoy it.

Using virtual-reality software to capture the images the same way a painter wields a brush, Steinkamp essentially is faking nature, with special effects to make art that fools the eye.

On a continuous loop, each of the four seasons runs the same length of time.

The tree’s movements are so rhythmic that watching can become hypnotic, with Steinkamp choreographing the piece so the tree moves to its own internal music.

“Its very simplicity lets us view it and understand the real complexity of a living tree,” says Jay Williams, curator of exhibitions and collections.

That intriguing title, “Fly to Mars, 5” seems to have nothing to do with trees.

“Steinkamp’s title suggests that the tree is literally flapping its limbs to take off and leave the atmosphere,” says Williams.

The number “5” in the title means that this is the fifth in a series; several museums have bought different editions.

Then there is the truly breathtaking photograph, “Giant Sequoia Stagg,” by James Balog.

The 242-foot sequoia grows in Camp Nelson, Calif.

Balog painstakingly captured this champion in nearly 500 separate frames as he rappelled down a neighboring tree.

He began photographing while hanging 25 stories above the earth, rappelling in increments of 15 feet, and panning left to right, shooting a level at a time so that no twig went unrecorded.

Icy moisture soaked him to the skin and his feet were numb when they finally touched the ground, four hours later.

Back in his studio, Balog digitally rebuilt “Stagg” from the 451 frames he’d captured in the air.

Then came two weeks of work at what Balog calls “stitching together a reasonable semblance of the arboreal tapestry.”

Along with Balog’s sequoia photograph and Steinkamp’s maple tree video, there are two oil paintings of classic palm trees by George Buckner, one of Florida’s famed Highwaymen.

In Buckner’s idealized “Marshland Scene in West Indian River County,” regal cabbage palms reign over white herons feeding in glassy water.

“Because Buckner’s simplified presentation of cabbage palms isn’t bogged down with details, it makes us grasp the larger idea of the tree as it exists in real life,” says Williams.

Buckner’s “Moonlight Scene in West Indian River County” is a glimpse of a water’s edge at midnight.

Another look at old Florida is Clyde Butcher’s large-format, black-and- white photo, “Loxahatchee River #1.”

The primeval scene may be in Palm Beach County but it appears to be from another world. Williams describes it as a representational, highly manipulated image.

Butcher is a master of control. Every choice he makes – from the large-format view camera, to a low shutter speed, to the time of day he photographed it — contribute to the photo’s unusual quality.

It is both dreamlike and sharply realistic.

Butcher’s choices allow us to see this particular view of the river and cypress trees with exactly the amount of detail that he wants.

“Butcher knew how the real-life color landscape would translate into shades of black, white, and gray,” says Williams.

He notes the slight blurring of the dark Loxahatchee.

“By using a low shutter speed, Butcher captures the slight movement of the water over time,” says Williams.

Last is Charles E. Burchfield’s “Midsummer Afternoon,” the oldest work in the show, painted in 1952.

Ghostly rain bands hover above a diminishing line of trees. Even the trees themselves appear to be weeping.

A visionary artist, Burchfield painted exclusively in watercolor.

His paintings are in many major museums in the US and have been the subject of exhibitions at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Modern Art.

A lifelong painter of nature scenes, Burchfield developed an increasingly hallucinatory style of painting after 1943.

He used swirling strokes and exaggerated forms to create transcendental landscapes.

Williams, who joined the museum in April, collaborated with the museum executive director and CEO Lucinda Gedeon to curate this show.

“It was part of the process of my getting to know the museum’s collection,” says Williams.

“Inspired by Nature: Celebrating the Beauty and Complexity of Trees” is on exhibit through Jan. 8, 2012.