On the eve of the Pfizer vaccine winning full approval from the FDA, a panel of top Cleveland Clinic doctors gathered to describe the ravages of COVID-19 in the hopes of convincing more people to get vaccinated – and wear masks until their second dose.

In their first press conference since the insidious surge of the Delta variant took hold, leaders from the health system’s five Florida hospitals spelled out the crisis at hand: They have reached their limit.

All five hospitals are running out of patient beds, including in the ICU.

They are also running out of oxygen, so intensive is its rate of use treating the more than 400 gasping patients in the system’s COVID units. On Friday, the hospitals were running on less than a two-day supply, down from the normal range of about a week’s supply.

And they are running out of stamina. Nurses are working 16-hour shifts, sometimes back to back, then going home to worry over their children heading back to school. Doctors at Indian River Hospital are toggling between their own practices and the hospital, after Cleveland Clinic canceled half their office appointments last week so staff could help out with hospitalized patients.

“No one diagnosis should take up 50 percent of the beds. No one diagnosis should take up 80 percent of the resources,” said Dr. Rick Rothman, the Vero-based chairman of the hospital medicine institute at Cleveland Clinic Florida.

Rothman said there are patients in the area’s freestanding emergency departments, emergency rooms that are not attached to a hospital, that have patients who need to be transferred to the hospital for care. “But we do not have the beds,” he said.

Rothman said he was asked by one doctor last week how to triage the sickest patients at his practice and the sick patients in the hospital. Judging by Rothman’s inflection, it was a question no doctor should have to pose.

“We are not an inexhaustible resource,” said Rob Lord of his COVID-19 team at Cleveland Clinic Martin North, where he serves as president.

“Our hospital is full of people needlessly suffering and in some cases needlessly dying,” said Lord. “Watching that happen is gut-wrenching on our caregivers.”

Dr. Greg Rosencrance, president of Cleveland Clinic Indian River Hospital, said staff is “a critical concern.”

“We are reaching a tipping point,” said Rosencrance. “We ask everyone to consider what this may mean for your loved ones, especially if they experience a health emergency and need critical care, such as stroke or heart attack care.”

He pointed to the fact that the hospital has already “reduced the scope of care we normally provide.” In late July, Indian River halted non-emergent procedures, and last week, reduced by 50 percent the number of visits to its physicians’ offices, though primary care visits and trips to the Scully Welsh Cancer Center were not affected.

Staff freed up by those cuts in appointments were sent over to the hospital to ease staff shortages.

Even the layout of the hospital has been shifted to accommodate the COVID overflow.

“‘We had to open new areas in the hospital for COVID-19 care as our previous units have reached their capacity,” Rosencrance said. “If we continue at this pace, we will see more instances where care for non-COVID patients is impacted.”

He said to date, no one has been turned away for emergency care, but added: “We are growing more concerned that if we continue at this pace we may not be able to care for all the patients when they need us the most.”

“If we don’t work together to limit the spread of this virus, there is no guarantee that should you get sick there will be a hospital bed available for you,” said Lord.

The ripple effect of so many COVID patients extends to those who are hospitalized for other conditions. The oxygen shortage is statewide; over the weekend, the city of Orlando asked residents to cut back on water use to save the oxygen used in water treatment so it can be used in healthcare.

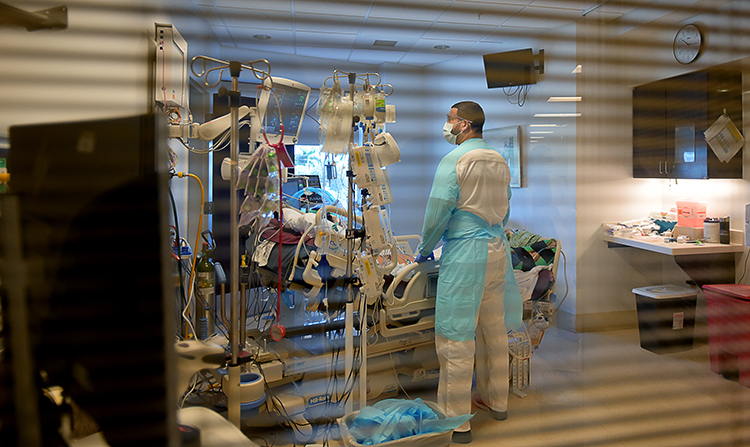

As the press conference took place, one floor up there were 30 severely ill COVID-19 patients, most of them unaware of their surroundings. They lay two to a room – doubled up to economize on space. Most if not all were heavily sedated and on ventilators. Most if not all were unvaccinated.

Again and again, doctors at the press conference stressed that most hospitalizations and nearly all ICU admissions could have been prevented had the patients gotten the vaccine.

Those ranks may close somewhat after action by the federal government this week.

With more than 200 million doses given in the U.S. alone, the FDA gave its full approval Monday to the Pfizer-Biogen vaccine. That approval is expected to push many employers toward implementing vaccine mandates, as dozens of healthcare companies have already done, though Cleveland Clinic officials say their vaccine strategy is still limited to education.

As of last weekend, the fully vaccinated rate in Indian River County stood at only 53.5 percent, even as cases jumped 16 percent to 1,174 for the week. With testing dropping inexplicably by half, the county’s positivity rate rose to a staggering 27 percent.

In terms of totals throughout the pandemic, in Indian River County 15- to 34-year-olds account for more cases than any other age category. On the second floor of the hospital, though, the case numbers took on new meaning.

In the recently converted COVID ICU, Vero Beach 32963 photographer Brenda Ahearn found the scene surreal, as living patients lay motionless under the heavy sedation required for a ventilator, many face down in the therapy known as proning. “These were not old people,” Ahearn said. She was moved by hints at the lives suspended by the virus; the strapping builds, the youthful skin, the tan on a man’s feet.

One ICU nurse at the press conference, Melissa Bennett of Martin Health, was similarly moved by her patients’ youth. She spoke in a strained voice as she described having to console children who had lost their parents to the Delta surge.

The patients “are my age, they’re your age. They are younger than what we’ve seen in the past and nearly all of them have been unvaccinated,” Bennett said. “Me and my nurses, we have held the hands of dying patients. I have had to console teenagers who lost their mom or their dad. That is traumatizing. It’s painful for me, it’s painful for the caregivers that I work alongside every day who are working tirelessly, extra shifts, 16-hour days.”

As those patients try to breathe through COVID-infected lungs, their collective gasps are depleting oxygen supplies, now down to a day-and-a-half to two days. The emergency is not just here, but across the state of Florida. Logistics teams are straining to come up with a plan to ensure trucks will still reach hospitals in the event of a hurricane.

The oxygen shortage is blamed not only on higher use. Since the start of August, deliveries have been hampered by a shortage of drivers trained to transport oxygen safely, and compounded by a return to limits on how long truckers can stay on the road. Those limits resumed after Florida’s state of emergency expired; as of Monday, Gov. Ron DeSantis had refused to reinstate the declaration.

“Hospitals are fighting with a hand tied behind their back and don’t have the same chance that they did when states had the public health emergencies declared,” said an executive with a hospital supply purchasing group, quoted by Bloomberg news.

The shortage also extends to patients discharged with oxygen concentrators, devices which capture oxygen from the air. Those patients are typically supplied with backup oxygen tanks in case the machines fail. Now even their supplies are at risk.

As for staff shortages, Cleveland Clinic Florida CEO and President Dr. Conor Delaney described a much larger problem than simply fatigue or workers contracting the disease themselves.

“The number of caregivers required to look after this huge number of patients with COVID-19, when taken with the nursing shortages and other caregiver shortages in Florida and across the U.S., means many hospitals in Florida have had to reduce the amount of routine non-emergency care that we can offer patients, just so we can have enough caregivers available to look after our patients.”

That translates to virtually “no surgeries that aren’t an absolute emergency,” said Delaney.

“Think orthopedics and many other surgeries and illnesses that normally would be treated in the hospital. That’s how dire things are going to be providing care to our communities.”

Delaney noted that in July, there were 35 COVID patients across the region’s five hospitals.

“As of today we have 397. This is by far the highest number of patients we have ever cared for since the pandemic began.”

He said 90 percent of the hospitalized COVID patients are unvaccinated. “And when vaccinated patients need to come into the hospital, it’s because they have other conditions or are immune suppressed so the vaccines haven’t worked quite as well. Even still, these vaccinated patients, when they come into the hospital, they rarely need to go into the ICU and almost never need to go on ventilators,” he said. They are “less likely to be very ill.”

Delaney said COVID fatigue may be a common complaint, but the remedy to the situation – masking and vaccination – has to begin in earnest now, and has to become routine for the future to deal with “the strength and longevity of this pandemic.”

“We aren’t going to wish away this infection. It’s going to be here with us for a while,” he said. “We have to be able to deal with COVID and provide healthcare beyond COVID 19 for all of you.”