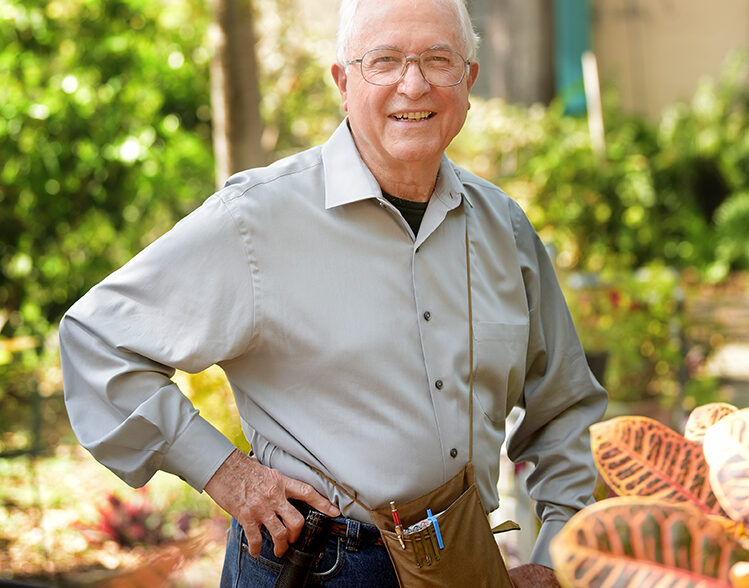

The latest offering at the Center for Spiritual Care shows, once again, that good things come in small packages. Spence Guerin: Paintings, Prints, Drawings and Statements contains 39 works he created from 1977 to 2021 in Florida, Alaska, North Carolina and New Mexico. Most are landscapes; two portraits and a small number of still life works are also on display.

The expansive range of dates and places are packed into paintings that should be a lot larger than they are to hold everything that Guerin has to say in them. And yet, they do that with plenty of room to spare. You have heard of people who are an inch wide and a mile deep; the same could be said of Guerin’s work. Once you jump into them you will want to spend time to explore their depths.

Take, for instance, Guerin’s 16-inch-high-by-36-inch-wide painting “Florida Pasture, Sean’s John Deere Tractor,” an oil on canvas executed in 1999 and 2000.

Don’t let the “nothing but the facts, ma’am” title fool you. As casually composed as it looks at first glance, this painting was created over the course of months that Guerin spent on site at Sean Sexton’s Treasure Hammock Ranch. This work is more than a picture of a tractor at rest in a Florida cow pasture.

Where to start? Perhaps the most obvious part of this composition is the sabal palm trunk that divides the composition cleanly in half, with the green tractor’s enormous left flank taking up most of the space on the picture’s right side. To the left is a long, lingering view into the pasture itself, with ranks of palms diminishing like so many fence rows into the hazy distance.

A few black cows are situated throughout the expanse, with pride of place going to a nearby red cow seen broadside with her head turned to gaze mildly at us.

That cow, who looks as though she has all the time in the world to stop and stare, is a cue to us to take the time to look a little more closely into her – and Guerin’s – world. Check out the tractor, whose manure-slicked rear tire is backed up to the picture plane for our viewing pleasure.

The presence of tire, tractor and palms is a clear indication that we are standing on a (mind your feet!) cow-calf operation in central Florida which, in the case of Treasure Hammock Ranch, has been part of the nation’s beef raising industry for 65 years. Although the fourth-generation rancher whose bottom usually fills the bucket seat above that tire is not in the picture, you can imagine him somewhere near; perhaps it is he whose shoes we fill as spectator for a little while.

When was the last time you had a painting show you what it feels like to be Sean Sexton?

Like Sexton, who was born and raised on his family’s Vero Beach ranch, Guerin is also a 100 percent Florida native. Born and raised just a few miles up the road in Melbourne, Guerin may not be a rancher like Sexton, but the two have been friends and fellow painters for many years. Long enough, in fact, that a criticism by Sexton of this very painting was met by Guerin not with chagrin, but with a redoubling of effort to correct what, to the rancher’s practiced eye, did not ring true.

Says Guerin, “Sean insisted that I didn’t have that red cow right.”

At the time of the criticism, the painting was all but finished. Nevertheless, Sexton directed his friend to spend some quality time just with the cows.

“He told me, ‘Just go on out there and sit down, and they will come right up and see what you’re doing,’” says Guerin.

“So, I did that,” he says.

“I had my palette with paints on it and a brush or two, put that canvas in front of me, and all the cows came around, including the red cow. After a time, they got bored and wandered off. I’d get up and move a little, and they’d come up again. I did that twice, until I thought I had enough. So that is the way this cow was actually finished. She didn’t have this pose the whole time, naturally. I used some of the other cows for the pose, but I got the color entirely off her.”

You may be wondering if the cow correction met with Sexton’s approval, but it seems that Guerin did not ask for further critique.

“I can only presume so,” Guerin says.

Sexton, however, does more than presume when he mentions his friend’s work. In a few thoughts he jotted down about the current show, Sexton says that the “craftsmanship and beauty” of Guerin’s art is akin to that of the gem cutter, whose dedication to painstaking detail slowly but surely reveals the brilliance of his material. Like the lapidarist, Guerin begins with a subject that looks for all the world like an ordinary fragment of earth.

Viewers who have seen the New-York Historical Society’s Hudson River School landscape painting show currently at the Vero Beach Museum of Art will be primed for viewing Guerin’s similarly deliberate art. In the VBMA show, Asher B. Durand’s 19th century oil sketches meet their descendants in Guerin’s 21st century works.

While Guerin’s Florida paintings are a far climatic cry from the Hudson River School’s output, his views of managed burns on Florida’s pastureland find equivalents in the curls of smoke seen in Coleman et al.’s hazy distances. And except for the small scale of his painting supports, Guerin’s scenes of Alaska’s grandeur are akin to Bierstadt’s panoramic views of the American West.

Guerin was a full-time resident of Alaska from 1974 to 1989, and still maintains a studio 50 miles from Anchorage, to which in more recent years he has repaired for extended painting trips.

The exhibition boasts several of Guerin’s Alaskan scenes, including “Matanuska Glacier at Dusk” of 1995, a vista seen through the windshield of Guerin’s vehicle with a bonus self-portrait of the lower part of his face, as reflected in the small mirror on the back of the pulled-down sunshade.

Indicating the painting’s distant, snow covered mountains, Guerin says, “On those mountains, you can look up and see the mountain sheep. In spring you can see the grizzly bear come out of his den.”

Despite the wonders across the breadth of our country that Guerin has spent weeks, months and even years painting, he always comes back home to Melbourne and its scenes of the Intracoastal Waterway, the Eau Gallie Causeway and Melbourne skyline, and the confluence of the Banana and Indian rivers, all of which you can see in this show.

One painting, however, a scene of a Little League baseball game set in the 1950s, is something that now exists only in Guerin’s painting of it. It shows a large sandy lot with a Little League game in progress, complete with the umpires, cheering section, and small-time concession stand that you expect to see in a recreation such as this one.

Guerin says that the first Little League game played on this lot (located behind the old Melbourne High School) was in 1953, when he was 12 years old.

Says Guerin: “This painting was done for somebody who played second base on this team and I was his assistant coach. His name is Kim Kahler and he lives in Valkaria, Fla. I was his coach when I was 14!”

As in all of Guerin’s work, the scene as it stands today is the first place he set up his easel. “I painted this scene on location with the two houses that remain there. This whole area here, it was lined with oaks. This (he indicates a vintage auto parked on a side street) came from Internet pictures, and these old bikes (parked behind the backstop) did as well. I went down to Palm Bay and photographed some Little Leaguers who were playing in a game. So, all this is contrived, of course.”

The sky in the painting takes up more than half of the composition. It is a radiant, cloudless blue, with a hint of the moon off to the upper right. That sky, which looks so smoothly natural, was anything but for the exacting Guerin.

“That is the third sky I put in that painting; I scraped the first two off completely,” he says.

“You can’t do a sky blue that is as luminous blue as the sky. It’s impossible.”

Thank goodness for the rest of us, Guerin still tries.

Photos by Brenda Ahearn