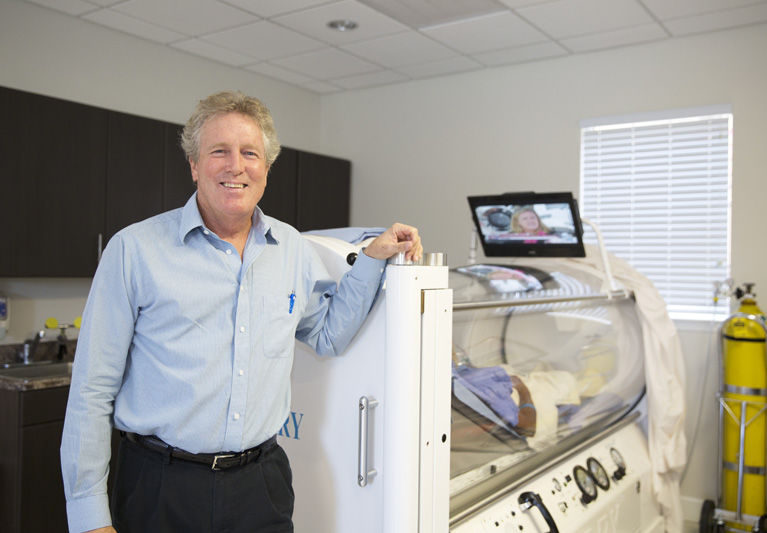

Dr. Tim Adkins, medical director for Sebastian River Medical Center’s wound care and hyperbaric medicine program, might have TV-realty-show good looks, but he takes a very dim view of a whole host of do-it-yourself projects.

On the top rung of his list is any project involving seniors and ladders.

The Centers for Disease Control is adamant in saying this country’s aging population is especially prone to ulcerous wounds and open sores that do not heal on their own. It also says falls and cuts can be major contributors to that problem.

Adkins is even more emphatic than the CDC about the danger of falls for seniors.

“I encourage everybody I know – if you’ve got ladders – get rid of them. Hire somebody else to do what you were going to do with that ladder, because those things are treacherous.”

Circular saws, hedge trimmers and even seemingly innocuous home decor items such as throw rugs also draw Adkins’ ire.

It’s not that the affable, silver-haired Adkins is in any way opposed to sprucing-up the old homestead. Rather, it is because he and his team often end up treating the non-healing wounds that can be exacerbated by falls, bruises and lacerations – and all the above items can contribute to that problem.

The actual root causes for most non-healing wounds, according to Adkins and the CDC, are underlying chronic diseases or medical conditions such as diabetes, peripheral vascular diseases, hematologic conditions such as anemia, heart and lung conditions, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and congestive heart failure, as well as balance problems, gastrointestinal disorders and vitamin deficiencies.

Adkins, who has practiced medicine for 30 years and been at SRMC since 1996, readily points to seemingly innocuous household items which, he warns, can lead to or exacerbate wounds.

Dishwasher doors are a perfect example, he says.

“People,” Adkins explains, “tend to run in to open dishwasher doors and the most difficult wounds to heal are ones in the lower extremities because of the poor circulation.”

As to the latter (not to be confused with those aforementioned ladders), Adkins cites what he calls “a gradual increase in the number of post-radiation injuries” as a modern cause of healing-resistant wounds.

Some medical treatments are culprits, too. “Radiation therapy is now being used a little bit more extensively for different kinds of skin cancers,” Adkins says, and that can lead to wounds that are “very difficult to heal.”

On the plus side, Adkins says medical science has come up with some powerful new tools and treatments to help with wound healing, including hydro-gel dressings, foams, hydro-fiber composite and alginate dressings, artificial skin substitutes, hand-held vacuums that debride and cleanse wounds, more effective topical antiseptics and, when called for, hyperbaric oxygen chambers.

Along with major modern advancements in wound care, Adkins mentions wound care methods from the ancient world still in use today, such as honey and – not for the faint of heart – maggots.

The use of honey on wounds pre-dates the pyramids, and while even the pharaohs didn’t know why it worked, doctors today do.

Bacteria, Adkins explains, produce biofilms. Biofilms are a complex network of fluids and proteins that are resistant to anti-bacterial medicines.

“You could put on all the Neosporin you want,” Adkins says, but in some cases it would be to no avail if the Neosporin can’t reach the bacteria protected by that biofilm.

Honey, Adkins continues, produces an environment that is “adverse for the production of biofilm.”

However, the best way to deal with most wounds is not to reach for that squeezable bear-shaped bottle of honey, Adkins says, but rather to “control bleeding, clean the wound, dress it or bandage it and then seek a medical opinion.”

“Patients who can get their wound healed within a couple of weeks from the time they injured themselves don’t need [wound care specialists] . . . for the most part,” according to Adkins, though he adds there are exceptions.

Any acute wound or one in which the bleeding can’t be stopped, he says, should be seen immediately in an ER setting.

And while Adkins says he has never used maggots, he admits, “I do know that there are settings where they are very effective.” (Maggots eat the dead tissue surrounding an open wound and effectively debride the area.)

The SRMC wound care and hyperbaric medicine program Adkins directs was just awarded the Robert Warner Award for Clinical Excellence by Healogics, the nation’s largest provider of advanced wound care services.

Despite that satisfying professional success, Adkins says, “I think the goal of all physicians is to try to put themselves out of work by getting people to take preventive steps and be able to better care for themselves.”

That means having patients actually using the walkers or canes they are prescribed for balance problems, removing slippery throw rugs from their floors, leaving power and hedge-cutting equipment in the garage and, yes, staying off those ladders.

Dr. Timothy G. Adkins is the medical director of the Center for Wound Care and Hyperbaric Medicine at the Indian River Medical Center at 13110 U.S. 1 in Sebastian. The phone number is 772-581-2070.